I have long had a lot of respect for the music criticism of Patrick Bateman. In his three oft-praised (and deservedly so) essays in American Psycho on poptimism and the rise of 1980s adult-contemporary, he scrutinizes the inescapable radio sound of the time, examining albums and artists so iconic, so popular, that they could have seemed too ubiquitous to bother to assess, to omnipresent to secure any critical distance from. Analyzing monoliths like Genesis's Invisible Touch or Huey Lewis and the News's Sports could easily have seemed as beside the point as evaluating the sunshine, or water (which Bateman also takes on, in a tour de force, back-of-a-cab lecture on the differences between mineral, spring, distilled, and purified waters and brands). But Bateman finds a way in by resolutely remaining on the surface, generating an implicit, searching critique through what his intentionally impoverished discourse — a masterful parody of vapid promotional press releases, as well as the indifferent "service journalism" music reviews that derive from and populate them — can't say.

His discussion of Invisible Touch is illustrative in this regard. It is not that the critical voice Bateman adopts is incapable of cogent insights: His claim that the album is "an epic meditation on intangibility" is plausible and not entirely banal, and the argument that the songs are "questioning authoritative control whether by domineering lovers or by government (“Land of Confusion”) or by meaningless repetition (“Tonight Tonight Tonight”)" is a provocative imaginative leap. But these points rest beside limp sub-clichés like "You can practically hear every nuance of every instrument" and "In terms of lyrical craftsmanship and sheer songwriting skills this album hits a new peak of professionalism," not to mention the casual factual errors (Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks of Genesis are identified at one point as Mike Banks and Tom Rutherford), racist asides, arbitrary comparisons, and unsubstantiated assertions of personal preferences. One grasps Bateman's point that critical intelligence is easily muted by a variety of biases, driven both by privilege and ignorance, and authorized overall by a crypto-"positive" attitude mandated by the culture industry's commercial orientation. Commercialism and "poppiness" and "clean" (as in ethnically cleansed as well as digitally pristine) sound are all equated with one another and elevated to the level of transcendent, self-evident social values. Of course music should be "clear and crisp and modern," and lyrics "positive and affirmative." These generalities license the underlying bigotry necessary to preserve the status quo that commercial pop music is always ultimately committed to.

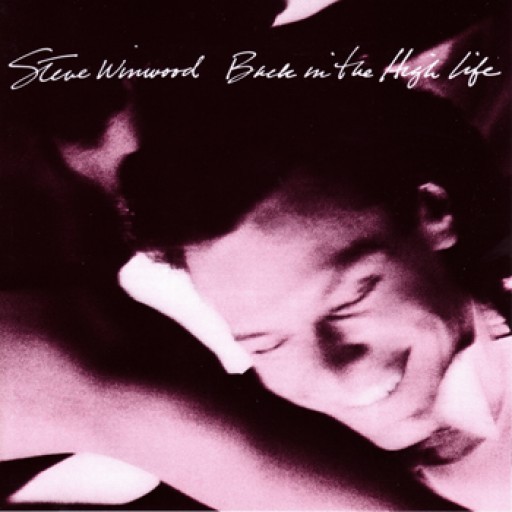

It's a shame Bateman didn't find the time in his general laying-waste to the shibboleths of 1980s culture to take down the single-most egregious purveyor of soulless yuppie aspirationalism and slick sterility: Steve Winwood, whose Back in the High Life must have soundtracked many of the overpriced and hyperattenuated meals at the trendy bistros and trattorias that Bateman lambastes throughout American Psycho. A cursory look, however, at contemporary reviews of the album suggest Bateman's satire would be redundant. Rolling Stone declared Back in the High Life "the first undeniably superb record" of Winwood's solo career, citing the "passion long smoldering in his finest work" that "explodes" in the opening track, "Higher Love," one of the seven singles drawn from this eight-song album. The reviewer celebrates the "deliberate precision" of each of the songs, which are also praised for each being over five minutes long. The New York Times declared after the album's release in 1986 that "the spare textures and loosely blocked arrangements of [Winwood's] music today make only minor concessions to contemporary pop sounds."

Winwood's vacuous hymns to hedonism and the "finer things" the aging rich can afford are, in their way, nearly as offensive and excoriating as the hallucinatory violence Bateman imagines visiting on the world of superficial splendor within which he has imprisoned himself. This is music that can only be enjoyed by someone who is dead inside. The smug and simpering ditties on Back in the High Life cauterize one's ossicles and vestibular nerves as effectively as aural battery acid, though they work not by administering pain but though their stupefying competence, which is so dull that it nullifies the very desire to hear. Much as Bateman represents himself and his peers as being inundated and ultimately annihilated by luxury, Back to the High Life oppresses with its fussy, ultragroomed arrangements, the sonic equivalents of the ludicrous menus and outfits Bateman meticulously details. ("Van Patten is wearing a glen-plaid wool-crepe suit from Krizia Uomo, a Brooks Brothers shirt, a tie from Adirondack and shoes by Cole-Haan. McDermott is wearing a lamb’s wool and cashmere blazer, worsted wool flannel trousers by Ralph Lauren, a shirt and tie also by Ralph Lauren and shoes from Brooks Brothers. I’m wearing a tickweave wool suit with a windowpane overplaid, a cotton shirt by Luciano Barbera, a tie by Luciano Barbera, shoes from Cole-Haan and nonprescription glasses by Bausch & Lomb.")

The song lyrics on Back in the High Life alternate between inspirational exhortations that demand uplift without effort ("Bring me my higher love!") to paeans to midlife crises overcome ("All the doors I closed one time will open up again!") to ominous warnings directed at unspecified others who are overstepping their boundaries ("Freedom Overspill"). The parade of guest appearances by some of pop's most boring voices (James Taylor, Dan Hartman, James Ingram) is complemented by rote musicianship from well-traveled session players, including Hall and Oates's drum programmer. Even the album cover, which seems to have provided the design template for chain-hotel and all-inclusive resort ads for the past three decades, serves up sepia-toned sanitization, a slice of boomer life cropped to its essence: a white guy (it could be Van Patten, it could be McDermott) smiling to himself in the center of the action, while indistinct bodies circle around him, supplying him with an unearned sense of ambient energy.

It is impossible to hear Back in the High Life now as it must have been heard then, as a coruscating collection of zeitgeist-affirming hits rather than a shocking display of hermetic entitlement and complacency. But then again, those were the "finer things" consumers yearned for, then as now. That its sophistication was so blatantly superficial just made it seem that much easier to reach.