Five Questions with __________ is an experiment with flash interviews. The series on poets continues with poet and essayist Jaswinder Bolina. I encountered his work after an essay in Poetry called 'Writing Like a White Guy,' which begins, 'My father says I should use a pseudonym. "They won't publish you if they see your name."'

As a devotee of words have you come upon any you can't bear to write?

I think there are a lot of words I don't want to write, but I feel I make discoveries when my poems take on those words or phrases directly. A few years ago, I wrote a poem about somebody yelling 'sand nigger' at me from a passing car. Obviously, that's not a phrase I want to repeat, but then I did—about fifteen times in that poem. Forcing myself to confront the language offered me a means of taking on that experience in what I hope is a provocative way. I think I discovered my own perspective on the incident while writing that poem. There are other words and phrases that are far less charged or offensive that I do this with too. Words like 'twitter' or 'spam' that become part of some meme irk me maybe just because I hear them too often. Actually, the word 'meme' is currently on the list of words that irk me for this exact reason. Others like 'irregardless' bug me because, well, just say 'regardless.' Whatever the words are, I find myself trying to work them into poems precisely because I dislike them. This forces me to attempt to take the irksome and commonplace and hopefully find a new perspective on it.

Do you wear shades in the sun or do your eyes face the day nudely?

I love your phrasing, 'do your eyes face the day nudely?' A few months ago, I would've said, they always face the day thusly, but after years of walking around with a sun-blinded scowl on my face and being asked, 'Are you upset about something?' by friends who'd run into me on the street, I've taken to sunglasses. For the record, I'm not now, nor have I ever been, upset. I'm just a little light sensitive and probably trying to remember what I've forgotten to do that day.

What did your childhood concept of a god or supreme being consist of?

I don't know that I ever really believed in much of that. I remember being taught to pray and to be wary of some omniscient arbiter in the sky, but nobody convincingly gave me the impression any of that stuff was real. There's a poem by Amiri Baraka written back when he was still LeRoi Jones called 'Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note.' I think it's the title poem of his first collection, and it's one of my favorites. By the end of it, we have the speaker tiptoeing into his young daughter's room because he hears her talking to someone. He finds her there praying, but as she's doing this, she's peeking, as he says, 'into her own clasped hands.' I think I was that kind of kid. The story religion told me didn't seem any more or less real than any of the works of fiction I read or movies I watched, and it still doesn't. At this point, I've decided that if there is a higher power, it's mostly beyond my understanding. After all, a single skin cell or neuron has no way of knowing that it's attached to the bigger, more sophisticated thing called 'me.' I realize a single cell doesn't constitute the same thing as consciousness, but I mean it as an analogy: I'm part of this bigger, more sophisticated thing we call the universe—ninety-six percent of which we can't even see—but I have little way of knowing what that universe is up to. I'm happy writing poems about what it's like to live in that condition. I'll leave it to the physicists and cosmologists to figure the rest of it out.

In what language would you most like your work to be translated, or transcreated, and why?

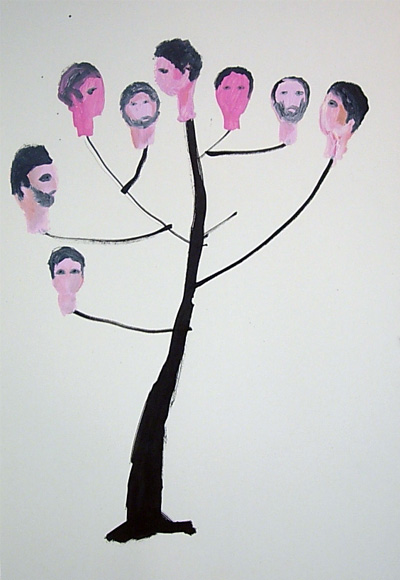

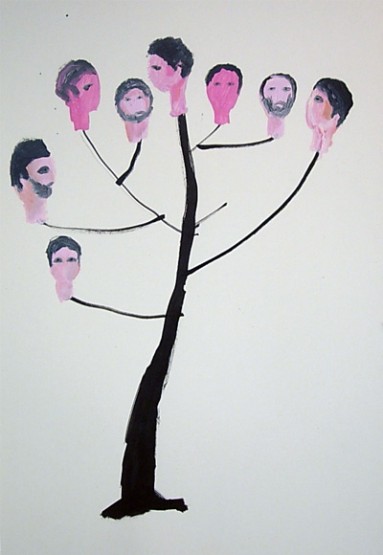

Arabic always looks like rippled water to me, Hebrew like a city skyline turned sideways, Punjabi and Hindi like vines dangled from a lattice, Chinese and Japanese dialects like feathers and bones. What I mean by this is that I'd love to see my poems translated into any language written in an alphabet different from the one we use in English and the Romance languages. Because I don't know those alphabets, the poems would turn into something akin to paintings. I also wouldn't have to worry anymore about tweaking or revising them any—something I do a bit obsessively—because I simply wouldn't be able to at that point.

What do you do at your loneliest hour?

I think I do the instinctive thing: I find a friend. Whenever I get to feeling lonely, which fortunately doesn't happen to me all that often, I just call someone or send a text or an email. Sometimes, if none of that works, I'll walk to a caféor a bar and just work on a poem till somebody kicks me out at closing time. All of these are attempts to communicate with someone, and I think I turn to them because loneliness isn't a product of being isolated. It's the feeling that nobody understands your perspective or your emotional condition at a given moment. This can happen in the middle of a crowded subway car or at a party with throngs of friends around. I worry some people feel this way for much of their lives. Lucky for me, I have a small battalion of friends and family who do understand much of my perspective, and it's easy enough to get a hold of them. Failing that, I always have the reader: this imaginary listener out there to whom I can describe whatever thing it is nobody else seems to understand. The reader always understands because the reader doesn't exist and is also always sitting right in front of me.