'In the late 1970s members of the US press metonymized Iran's hardliners as turbans and its moderates as neckties.' —Necktie

Western fashion is rarely subject to the same scrutiny as non-Western fashion garb. Rare, too, is the invitation to closely inspect men's fashion as an exhibitor of cultural values, masculine authority, and significantly, capitalism. (If you are a non-American/non-European woman, the chances that your habit will be cause for public and also political consternation is the equivalent of three cherries clocking in unison at a slot machine.)

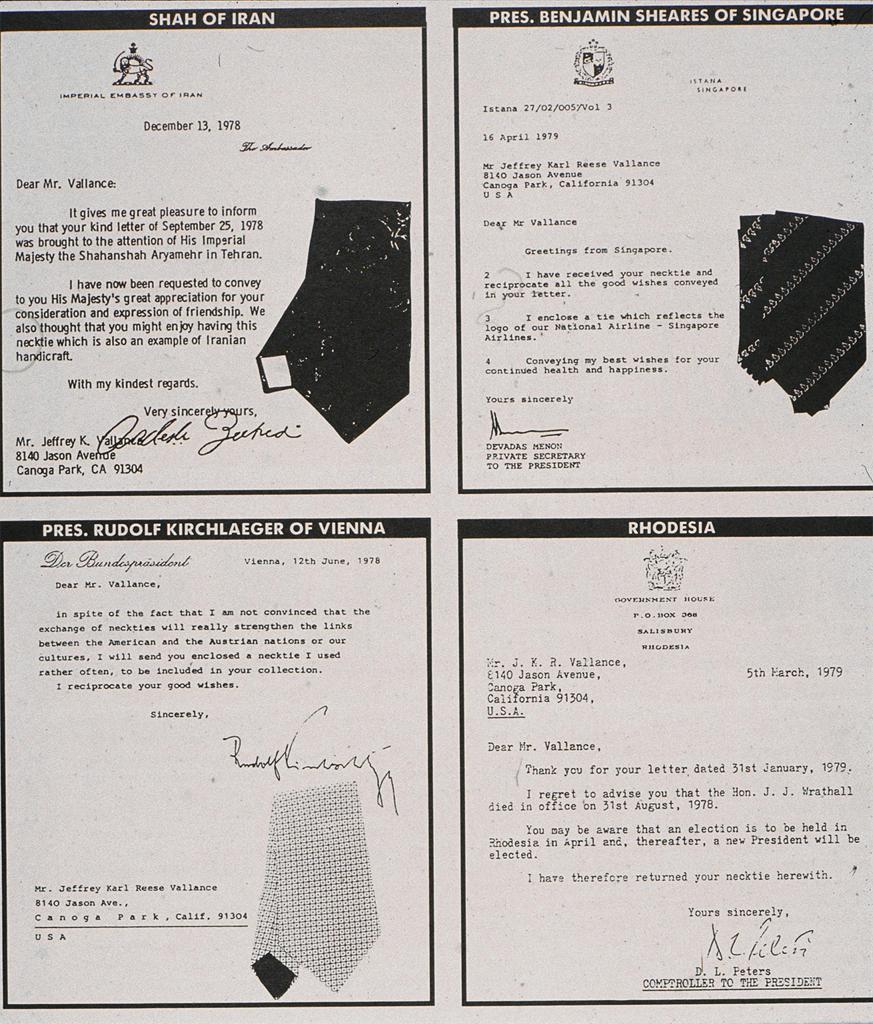

That's why the correspondences pictured above are a delightfully surprising find. In 1978 American artist Jeffrey Vallance sent one of his ties to dozens of government leaders with the request that they send back one of their own, as 'a token of friendship and as a symbol of the cultural ties between our nations.' By 1979, at least 47 had complied (though Pope John Paul II opted to send back a medal and an autographed picture).

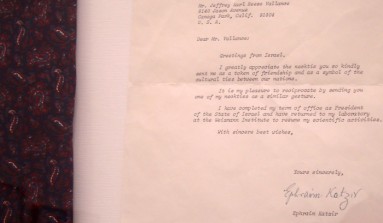

Outgoing Israeli president Ephraim Katzir effusively enclosed his tie with a curious tangential note: he had 'returned to my laboratory at the Weizmann Institute to resume my scientific activities.' The letter is warm, but Katzir is quick to point out that he had already traded in a tie for a white lab coat.

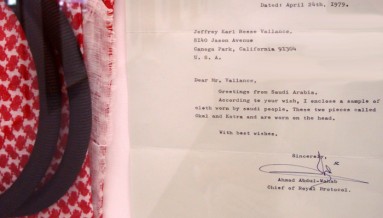

The royal House of Saud enclosed 'a sample of cloth worn by saudi people; these two pieces called Okal and Kotra and are [sic] worn on the head.'

It's the letter from the Imperial Embassy of Iran, signed by diplomat and prominent ambassador Ardeshir Zahedi, that opens a window into hardwearing debates about clothing and capital in the weird rhizome of cross-culturality. Zahedi writes:

Dear Mr. Vallance:

It gives me great pleasure to inform you that your kind letter of September 25, 1978 was brought to the attention of His Imperial Majesty the Shahanshah Aryamehr in Tehran.

I have now been requested to convey to you His Majesty's great appreciation for your consideration and expression of friendship. We also thought that you might enjoy having this necktie which is also an example of Iranian handicraft.

With my kindest regards.

What a portentous dispatch this would become, sealed without the benefit of foreseeing the Shah's necktie as a noose. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution (which contrary to Khomeini's promises he would never enforce mandatory hijab for women, did) the sale of men's neckties was banned. Javad Dorodian, a leader of the shirt tailors and retailers union commented that even the union logo had to be changed, 'and the tie had to be removed.' As with nearly all clothing restrictions in Iran, though, this one has been subject to some loosening, given that politicians in several millennial elections have been photographed wearing a tie despite its ban in government offices.

The dominating idea is that ties were banned on the basis of 'Western decadence.' But that doesn't make as much sense as other historical markers that would have (for the theocratic elite and common denizens alike) concentrated post-imperial disgust into a single garment. Anglo-European encroachments on Iran's oil reserves, for one. The necktie as an icon of 'opulence' makes sense only in that larger picture of Western neo-colonial theft, assassinations, and collusion with a self-described imperial royalty who were odiously regarded by the Iranian people for their extreme wealth.

I find Zahedi's characterization of the included tie as 'an example of Iranian handicraft' to be extraordinary. By late 1977 (almost exactly a year before he sent the tie to Vallance) popular resentment against the royal family was gaining steam. The populist, even indigenous, framing of a 'Western' piece of clothing (and one associated with the business and political elite, not peasants) is fascinating.

And a closing query (meant without even the slightest trace of political nostalgia): what would it mean for an artist to replicate Vallance's experiment today?