In the midst of the nearly universal denunciation of the Charlie Hebdo killing, an ethics and worldview so generic as to approach being simply "The West"* sought to bolster its already secure position.

(Note: this, and what follows, isn't to speculate on the reasons that 4 million people came out onto the streets, in ways that obviously can't be reduced to them being "duped" or "manipulated." That's a question I won't even begin to approach, being neither there on those days nor living in France generally. This long text on libcom, just translated, tackles that at length, especially in terms of the notion of the citizen. My concern, instead, is how a certain world view, one pushed both by states and in the media, has attempted to frame and give image to a situation that far exceeds it and, by so doing, reinforce its position.)

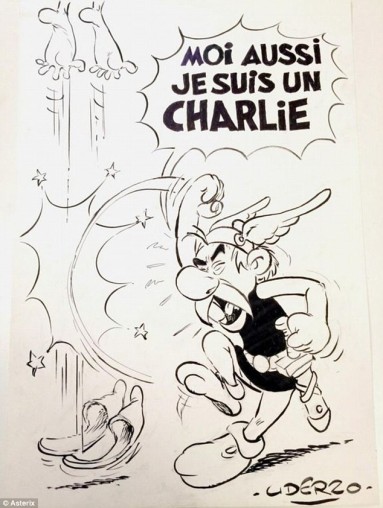

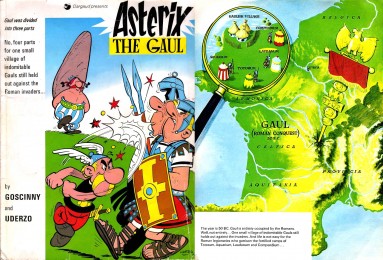

It’s unsurprising, for instance, that Albert Uderzo, creator of Asterix, came out of retirement to draw his support for Charlie: what emblem more fitting for the entire discourse than a 20th-century cartoon of an ancient plucky Gallic warrior fighting off the Romans, i.e. a martial empire that, in Asterix, doesn’t know how to take or recognize a joke. Yet in Uderzo's new drawing, the shoes from which the enemy has been punched free are not Roman sandals but babouches – heel-less slippers unmistakably coded in France as North African. The symbolism is so overt that it barely counts as symbolic, just the direct expression of a sneering imperial whimsy. Asterix, defender of old Gaul, comes back from the mythical past to expel the clear and present threat to French liberté, égalité, and fraternité: the descendants of those whose enslavement and colonization so profited France, from before it declared the rights of man in 1789 to when it ratified the Constitution of the Fifth Republic in 1958, that it literally forms the basis of its wealth and geopolitical clout today.

France, the plucky historical underdog...

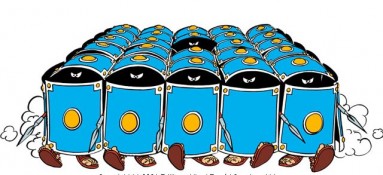

... Romans as the faceless, humorless enemy, with shields as veils

Even aside from giant foam pencils getting waved about like a NHL game costumed by Max Ernst, the entire affair has bordered on the surreal, with all the fitting marks of a late-stage and freaked-out colonial power. For behind all that talk of unity lies a manic and fractious instability, as the state and its mouthpieces, official and otherwise, swerve between pulling punches one moment (“it was all just satire, we swear, they mock all religions equally, they only drew Taubira as a monkey because that’s what Front National says”) and lashing out the next (up to 100 arrests and counting, for violations of free speech by those who sympathized with the attack, or with the anger behind it). All, of course, underwritten by continual recourse to levels of self-caricature (about that transhistorical French spirit) that one expects more from Fox and a seriously surging and actually frightening brand of white ethnonationalism that would make Fox proud.

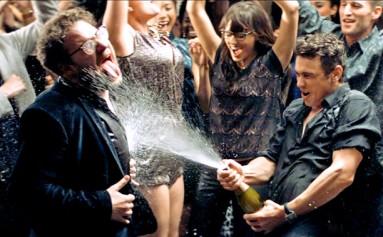

But just prior to this, the words free speech were getting thrown around with the same frequency and conveniently sloppy ease for another situation dominating the American news cycle, that of The Interview. The film itself is, of course, just the n-th iteration of Appatow-Dugan-Stoller bromantic banality. It's replete with spite for any humans other than its chosen few, which primarily means straight white guys so consumed with a deep and unabiding horror of any real existing queerness that they set up a blind of fake transgression – oh God, what would it mean for two men to care deeply about each other?, oh God, we do care, we do! as if that wasn’t the plot-line of a good half of all American movie and TV production – while quite literally cramming missiles up their asses.

And so it spits in the cake of others and eats it too. The only salient difference from the previous offerings of this ilk is that this film is actually, rather than just implicitly, supported by the State Department.What happened needs no rehashing, other than to note just how sacrosanct and widespread was the idea that the film's embattled release had everything to do with freedom of speech, that this freedom is a right at the heart of American experience, and that it must be protected – which essentially means helping cover the losses of an enormous multinational by paying to see the film. An editorial from The Washington Post sums up the basic position: "Freedom of speech and freedom of expression are hallmarks of American life, and we must jealously guard these values from both internal and external threats." But it wasn't limited to conservative rags, as even The Onion's AV Club, normally at least semi-intelligent, hails it as a “triumph of free speech” – even if it notes that it doesn't make its satire particularly good.

What went missing through all of this, though, was any recognition of a full-scale category error at work, itself a product of a slow historical erasure that renders the phrase free speech at best null and void, at worst a tool of those from whom speech is supposed to be protected. This error can be seen in a simple fact. Thanks in part to the Sony hacks, we know just how much the entire apparatus of The Interview cost. $44 million production (including $8.4 million for Rogen and $6.5 million for Franco), plus $35 million domestic marketing budget, plus $12 million foreign marketing budget. In short, this alleged triumph of subversive expression, the plucky underdog uncowed by pressure foreign and domestic, cost $91 million to produce, with the hope, of course, that it would earn global returns far beyond this. (Indeed, its stunted release is by no means a threat to this: it's already hit $40 million in online sales and streaming, making it Sony's biggest online release by more than 400%, as the #2, Snowpiercer, came in at $8.2 million. Besides, given how shitty the film is, the scandal was the best thing that could have happened to it, expanding its nervous titter into a public cause.)

To get a sense of this scale, $91 million dollars also happens to be the price of:

One Lockheed Martin F35 Lightning II fighter jet (with a million or three to spare), provided that production hits expected capacity in 2018.

The Chelsea Football Club, at least when Roman Abramovich bought the team in 2003.

One of Laksmi Mittal's mansions on Billionaire's Row in London where Abramovich also lives.

The amount that Suntech Power Chairman/CEO Dr. Zhengrong Shi made from the $290 million market value leap in Suntech Power stocks after the company announced its plan to invest $10 million to build its first solar factory in the US.

Secil (Companhia de Cimentos do Lobito) Cement company's investment in a cement and clinker factory constructed in Angola's Benguela province and which has the production capacity of 600,000 tons of cement per year.

The seven-year contract that kept Mike Piazza at the Mets.

The amount that Chicago's Northern Builders Inc. made by selling six suburban industrial buildings comprising a 1.4 million-square-foot portfolio to Hillwood Development Co.

The 2009 auction cost of Titian's Diana and Acteon.

The sale to Kimco Realty Corp of the Crossroads Plaza shopping center in Cary, NC, which is 670,000-square-feet and includes more than 60 restaurants and stores, including Best Buy, Dick's Sporting Goods, Toys 'R' Us, Old Navy, and Marshalls.

The aquisition cost of Enfield-based New England Bancshares Inc. by United Bank a year ago.

$24.9 million more than the 2015 $66.1 operating budget of the city where I live along with 50,000 other people, a food desert whose planners dream of gentrification and where stretched-thin resources mean it takes more than 1 hour to commute by bus to a city only 14 minutes away by car.

The point is that things that cost $91 million are not speech acts, free or otherwise. They are mergers and contracts and weapons, the rarest of old commodities and the new fortresses which hold them. They are facts of industry and territory, the Mets and the metropolis. They can only be, because that level of coordination and extraction make them the property and extension of states, corporations, or individuals with so much amassed wealth that they may as well be states or corporations, even if they prefer to call themselves collectors or philanthropists or James Franco.

$91 million things are ventures and investments, acts of war against what could never be worth that much. They do not need to be protected. They are what we need to protect ourselves against, future-shaping dreadnoughts of force that structurally cannot opine or express themselves, and especially not against injustice. They just do. And no matter what they say, or who does what to whom with what kind of missile in what setting, the only opinion they actually hold and send out "through any media and regardless of frontiers"

To imagine that The Interview has anything to do with free speech wrongly imagines that it has anything to add to the world other than a recitation of the current state of American empire. It's the Pledge of Allegiance wreathed in cut-rate dick and weed jokes. Only those who consider a factory or a football club or a shopping mall or a fighter jet to be an unalienable right – in short, only those who see property as an expression of individuals, rather than the historically-produced category that underwrites such a notion of individuals – can hold this position of it as being free speech. It is, not coincidentally, the default position of a long moment where conditions of global wealth that support it make it more unstable and volatile, just as the idea of national unity channels a nostalgic call for a socially-secure and homogeneous national composition that simply doesn't exist.

In this regard, the link between Charlie Hebdo and The Interview has less to do than it seems with satire, the limits of humor, and whether one should be killed for a cartoon. (No, but there are so many other things for which people should not be killed but are, like being black in America, that it adds little specificity. Moreover, the category of offense/being offended misses the point so often, given that "equal opportunity offenders" doesn't mean as much when some of those targets of satire – say, North Africans living in France – are recurrently targeted by police in much more literal ways.) Instead, they're linked by something else that goes missing amongst all the talk of free speech, a simpler double question: protection from whom or what? protection by whom or what? There is a tremendous difference between, for instance, demanding the state protect your right to vilify those who that state actually kills overseas and targets at home, and demanding that the state not beat, kill, or incarcerate those who express opinions hostile to the predominant situation. The former is not actually a demand, just an exhortation for things to remain constant, if not to return to "how they were" for a certain segment of the population. And the latter is a not a demand that can be answered by the state, because it is a challenge to it, one that people work tirelessly to raise and raise again.

Nearly four decades ago, Serge Daney wrote that "All films are political films," by which he meant that there's just no such thing as neutrality. Everything that is made, whether on the cheap with stolen equipment and images or for literally hundreds of millions of dollars, is partisan. The question is partisan for what, in defense of which grasp of the world, on the shoulders or at the throat of whom. It seems to me that any real engagement with cultural production of any variety, an engagement able to be both rigorous and reckless, subtle and furious, deserves to start with that question, and with taking jokes too seriously and stone-faced solemnity as the farce that it is. Where it goes from there strays into questions of method, which open conversations worth having again and again far outside academic journals, far beyond paywalls and gallery walls, and far outside some delimited terrain of "culture" picked over by ideology critique. It likely means working to see something like the cinema, for instance, not as a collection of films but as an enormous and contentious circuit in which the films, and especially their plots and how it "codes politically," are only one tiny moment.

But those are a longer and thornier questions, ones that should be conversations than a monologue. What seems clear enough, looking back over the last months, is something that has been said again and again over the last century. That to fully recognize the contours and history and projects of things that cost $91 million will require leaving behind, together, a form of criticism where we comment on these juggernauts as if they were speech and where we act as they were the expressions of individuals who might listen when we tell them that Avatar is imperialist bullshit.

In place of all that, we need forms of critique that are actually inseparable from our efforts to develop communities of care and struggle, where the point of criticism isn't the thing to be decoded (or to be rewarded for doing so) but the development of actually popular cultures that will never be worth $91 million and the amplification of what otherwise goes unheard. I think we already have these, if not as forms than as instances and moments, but they often go unrecognized because they just don't align with what we have been taught – and perhaps what we teach, when we're lazy – that criticism means. These kind of critiques alone might be able to help withstand the present, which means, in no small part, destroying the notion that money is an opinion to be expressed freely.