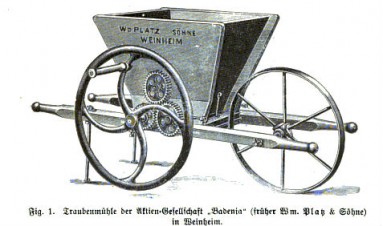

Illustrations from Jahrbuch der Deutschen Landwirtschafts-Gesellschaft (1891)

"Take a look at the wheat field that has been brought up to perfection, as it stands! Yellow as gold, with the sheen of the sea, billowing from sky-line to sky-line like an ocean of gold, where the wind touches the rippling wave crests with the tread of invisible feet!" -- Agnes C. Laut, "Harvesting the Wheat" (1908)

In 1786 Russia's Catherine the Great invited the Mennonites to leave their West Prussian farms and settle the vast, empty steppes she had seized from the Turks. She knew their reputation for hard work, which they made evident by excelling in dairying, crafts, trade and farming, and so prospering when others failed. Industriousness they had in spades; what they lacked was religious freedom. To sweeten her offer the good czarina promised them tolerance and the liberty to worship as they pleased. For good measure she also exempted them from military duty and granted them license to operate breweries, flour mills, stores and bakeries.

"'I don't need fancy things like Amanda,' declared the hired girl. 'I wear the old style o' clothes yet. And for top things, why, I made up my mind I'm goin' to wear myself plain and be a Mennonite.'" -- from Anna Balmer Myers's Amanda: A Daughter of the Mennonites (1921)

"In the cultivation of the earth, two modes may be adopted; either it may be cultivated in common or individually; the disadvantage of the former is that it makes no distinction between the weak and strong, the idle and industrious: for superior exertion and ability there is no superior reward. Under this system, the world would not be reclaimed -- men will not willingly labour for others; to stimulate exertion, rewards must in some degree be proportioned to desert." -- John Wade, History of the Middle and Working Classes (1834)

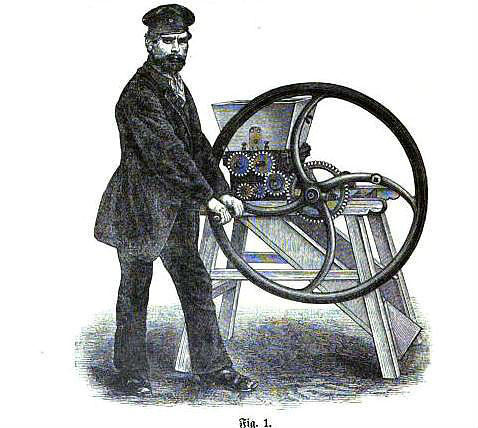

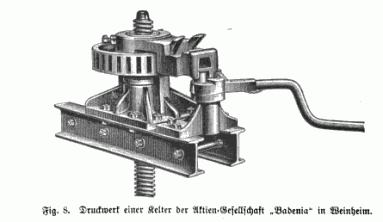

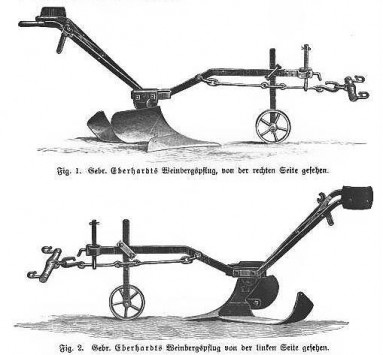

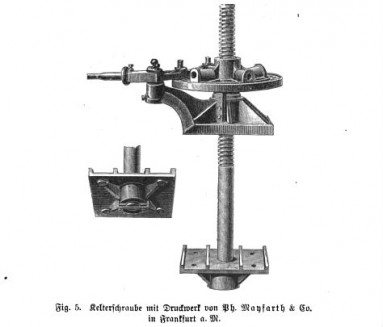

The pious Prussian sectarians found Catherine's offer too impressive to refuse. Hundreds of them packed up and headed east for the fertile banks of the Dneiper River, among whose lush forests of oak and wild pear they made their new home. The climate resembling that of their Prussian homeland, they lost no time turning Russian soil to account. Primitive wagons, plows, harrows and flails they used to cultivate rye, oats, barley, potatoes and vegetables. They fished, reared livestock and generally flourished. In growing cereal grains they showed themselves expert hands. Markets as far away as Britain and Italy clamored for Mennonite wheat (consumers in the latter country found that it made particularly nice macaroni). Increased demand made necessary a comprehensive upgrade in the scale and technological sophistication of their farming techniques.

"Pray for a good harvest, but keep on hoeing." -- Slovenian proverb

The transplanted Mennonites adopted threshers and other machines and ditched their wagons and flails. With the abandonment of customary equipment certain time-honored harvest traditions perished. Late summer of past years brought men, women and children to the fields. There the men would swing large scythes, mowing down the stalks before them, as the women followed them with food and water. The mowed wheat the men piled on the ground. Later they would bind it into sheaves and leave it to dry in the sun. Once dry these sheaves they would pitch into hayracks and haul to the farmstead. There they would thresh it by laying it on the ground and having a team of horses drag a stone over it. This threshed grain they stored in special bins in the attic of their homes, which featured steep roofs designed for this purpose.

Recipe for Obstmoos from Mennonite Foods and Folkways from South Russia: "1 cup dried apples, 1 cup dried prunes, 1 cup raisins, 1/2 cup dried peaches, 1/2 cup dried apricots, 8 cups water, 1-2 Tbsp. cornstarch, 3/4 cup sugar, 1/2 tsp. powdered cinnamon or 2 sticks cinnamon, 1/2 tsp. salt, 2 cups milk. Wash fruit and place in kettle with water. Cook until almost tender. Prepare thickening of cornstarch, sugar, cinnamon and salt. Add a little water. Stir into the Moos. Cook 5 minutes. Cool Moos. Add milk. Hint: If using stick cinnamon, add before the last boiling. Also, adding 2 Tbsp. vinegar enhances the flavor."

A man could mow two acres a day. Grueling work, it made him look forward all the more to his midday break, at which time his and the other men's wives would produce ripe watermelons, crullers, cherry pancakes and a thick fruit soup known as Moos. This feast they washed down with cups of coffee, milk and cold water.

Bare fields signaled the end of the season. The last load of wheat to leave the field the farmers crowned with sheaf of wheat on a pitchfork stuck upright into the top of the load, a sign to the whole village that they had cleared the fields, and that the end-of-harvest celebration could begin. Women decorated the final sheaf with flowers and the village church with wreaths of wheat. More crullers and Moos appeared on tables, and disappeared shortly thereafter. For Mennonites work was sweet -- if for no other reason than it made their hard-earned leisure even sweeter.