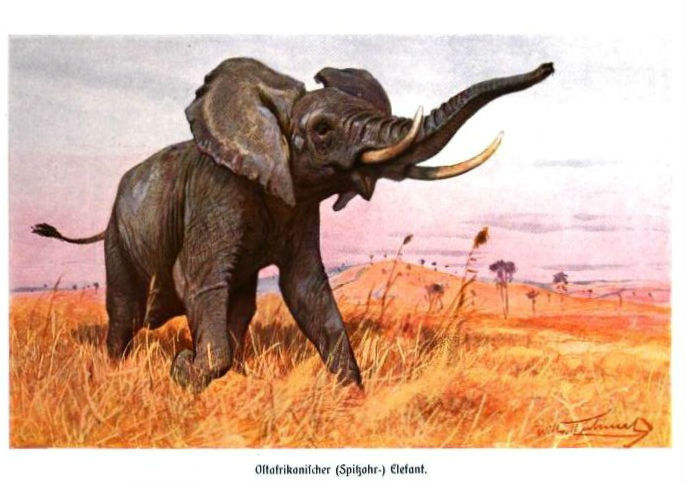

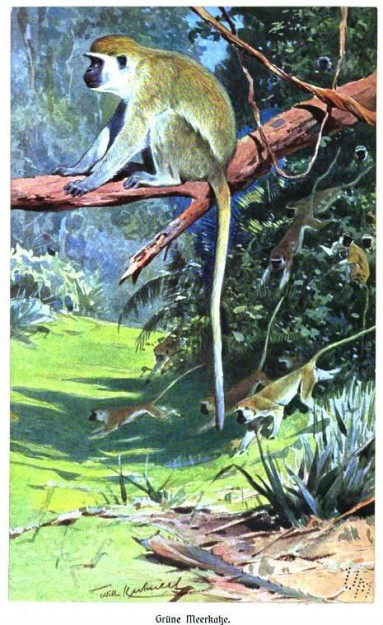

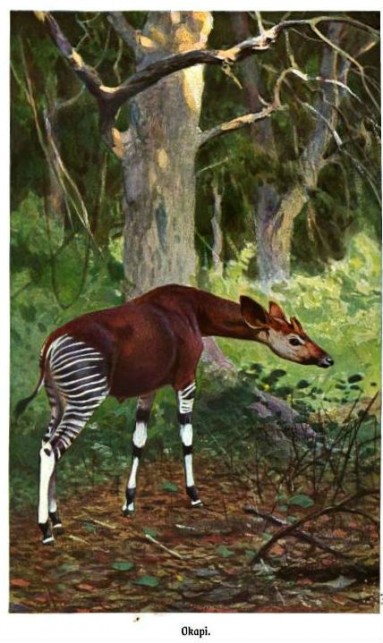

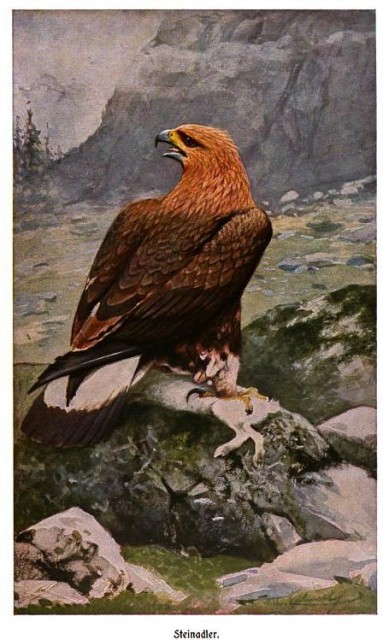

Illustrations from Brehms Tierleben: allgemeine Kunde des Tierreichs (ca. 1893)

More than the pacing, antic tapir, more than the dancing bear did visitors to the Jardin des Plantes love Castor and Pollux, the two elephants

"There is no creature among all the Beasts of the world which hath so great and ample demonstration of the power and wisdom of almighty God as the elephant." -- Edward Topsell, The History of Four-Footed Beasts (1658).

held captive there. Brother and sister (twins, in fact), Castor and Pollux never ceased to delight onlookers. Ladies marveled at the delicacy with which the pachyderms' trunks probed for the morsels of white bread they'd bring them. Men stood thunderstruck by their great size. Children squealed with excitement when for a small fee the elephants’ keeper would set them on his charges’ backs for a march across an imaginary Serengeti.

Even the most jaded of journalists could not help but feel themselves wooed by the charms of these animals. One Paris correspondent for The Times of London deemed them “as lively and playful as kittens," noting how they would “gallop and strike each other with their trunks” and later “lie down beside each other" when such hi-jinks tired them.

Only the dark pall of conflict could break the spell that for seven years Castor and Pollux had cast over the city. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 brought an end to the idyll enjoyed by these "pets of young Paris." The threat of imminent siege forced Parisians to abandon their recreations in order to prepare themselves. Their days they spent amassing arms, building blockades and laying by stores. Some 220,000 sheep, 40,000 oxen and 12,000 pigs they herded into the Blois de Boulogne -- meat enough for even the most protracted embargo, they believed.

A French writer who survived the siege said that "he will ever feel grateful to Bismarck for having taught him that cat served up for dinner is the right animal in the right place."

This proved an unrealistically optimistic estimate. The siege lasted well into winter. By late autumn the Parisians had consumed all their livestock. Beleaguered, wracked with hunger, they found themselves resorting to strange flesh. First they ate their horses, all 70,000 of them. Then they nibbled their pets. Old maids roasted lap dogs and mourned them as they sucked marrow from tiny ribs. House cats went missing only to turn up in butcher shops, filleted and dressed with paper frills and colored ribbons. Housewives served the small pink and white carcasses broiled with pistachio nuts and pimientos. When even the stock of felines dwindled, a "rat market" sprang up in the Place de Hôtel de Ville. Even such meager meat as this came in scant supply, the price it commanded putting it out of reach of the poorest citizens, who had only “siege bread

Recipe for siege bread:

Wheat ... 25%

Rye, Barley, Peas, Vetch ... 5%

Rice ... 20%

Oats ... 30%

Starch ... 10%

Bran .... 10%

,” a dark, sour-smelling mass made mostly of sawdust, to fill their bellies.

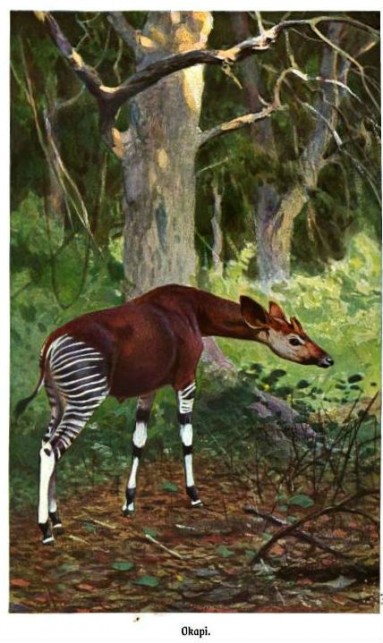

War creates opportunity for those savvy and well-heeled enough to seize it. In this, the siege of Paris stood as no exception. Provisions in the city stretched to the limit, the various attractions of the Jardin des Plantes rapidly went from luxuries to liabilities. One dwarf zebra, two buffalo, two Sambour stags, twelve carp, two yaks, three geese, one small zebra, one lot of hens, one lot ducks, eleven rabbits, four reindeer, two Nilgai antelopes, one doe, two elk, one antelope, two camels, one yak calf -- these exotic creatures were all placed on the auction block and sold to the highest-bidding butcher.

So catholic were the appetites of the Parisian elite that winter that Victor Hugo likened their stomachs to Noah's Ark.

An English butcher named Deboos claimed the lion’s share of the menagerie. He catered to Paris's wealthiest citizens and counted Baron de Rothschild among his best customers

The good baron had purchased all of Deboos's cassowaries.

. To him went also Castor and Pollux, whose sale happened to coincide with a situation of particularly acute dearth. The city had nearly exhausted its store of meat, and the moneyed classes, invoking the folly of maintaining a zoo under siege conditions, clamored for something new, something unusual, to delight their palates.

"M. Trintan ... relates in particular that an Egyptian parrot had its wing broken by a splinter of a shell, and that sometime afterwards, viz, in 1879 it welcomed with loud greetings the veterinary surgeon who had attended it while suffering from the wound." -- from an article in an 1877 issue of The Country.

Deboos admitted he knew nothing about slaughtering elephants, but, sensible to the caprice of the rich, he saw it as in his interest to learn on the fly. Enlisting the help of a zookeeper and a gunsmith, he settled on Castor as his first victim. The keeper commanded Castor to kneel and rest his head on a wooden block. The elephant obeyed.

The gunsmith meanwhile raised a carbine to his shoulder, took aim and fired. The explosive steel-tip bullet it discharged struck home, but it did not kill Castor. Blood gushed from the wound it made. The elephant appeared surprised and somewhat confused, perhaps thinking he had suffered some accident. Yet he continued patiently to rest his head on the block. It took two more shots to the skull to fell him.

"Love, in animals, has not for its only object animals of the same species, but extends itself further, and comprehends almost every sensible and thinking being," writes David Hume. "A dog naturally loves a man above his own species, and very commonly meets with a return of affection."

Pollux received a more humane dispatch than that granted her brother. She died of a single shot behind the ear.

The abundant meat these animals rendered — some 1,500 kilograms — commanded the princely sum of sixty francs per kilo. Restaurateurs printed new bills of fare to advertise the exotic new dishes

"The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a new star." -- Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

they offered:

Emincee of elephant! Elephant vinaigrette! Stewed elephant with camel's hump! These dishes the

beau monde of Paris downed with gusto. Gourmands reported the trunks and feet tasted especially fine.

The days of exclusive culinary adventure ended with French surrender on January 28, 1871. As a gesture of goodwill Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck directed food relief to Paris by the train-load, which the city's poor, who had little else but seige bread to nourish them and who had perished by the tens of thousands during the hostilities, no doubt gratefully received. Richer sorts, however, perhaps sniffed at the idea of eating rations, memories of their earlier zoo-animal dinners still vivid in their minds. Ennui bred by peas and sausage was something only they could know.