None of us knew whom “Justine Sacco” was, before she tweeted the racism heard round the world, and so there is (or will be) the urge to step back from the text itself—the tweet in question—and talk about her. Who she is, and what she is doing, and how she will suffer, or what she meant, and all that. In fact, there is no #HasJustineLandedYet without imagining her, without picturing (and enjoying) the spectacle of this clueless racist on an 11 hour plane journey, obliviously floating through the friendly skies while the world seethes; the whole thing is only interesting because we know something she doesn’t, because of the suspense of waiting for the big reveal. And the more we make it about her—thereby transforming this event from which her absence was the crucial thing—the more we can only become sympathetic, or at least less cruel: if she’s a person, she’s a flawed person, yes, but she’s not the racist caricature she became in our imaginations. If she is more than the text of her tweet, then our reaction to the text of her tweet comes to feel wrong, cruel, excessive, ugly.

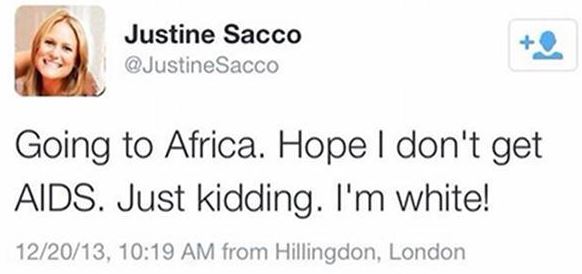

And that’s fine! While she was still in #HasJustineLandedYet, she didn’t really exist. She was a joke. When she landed, she became a real person (to us). And there’s nothing particularly pretty about many thousands of people shaming and humiliating a single person, who they don’t know; whether or not the shame and humiliation is justified, it’s nevertheless unsettling to realize how irrelevant the facts of the matter actually turned out to be. She could be the worst person in the world, or she could be the sympathetic possible version of herself—since the material in question will only allow so much sympathy—but since her absence from the drama was the key thing, it really doesn’t matter at all. She, herself, is irrelevant, and so there’s an arbitrariness to the spectacle that is, I’ll say again, unsettling, if we can see ourselves in her shoes: your good intentions, who you really are, will not save you. The only thing that mattered, in the event, were the words she wrote in a tweet, which were judged, found guilty, and granted no appeal, all without any opportunity to face her accuser. Who she really is was stripped away; what she meant was irrelevant; how she might defend herself, or respond, was eliminated by circumstance; and any kind of counter-testimony or context was rendered impossible. It was simply these words:

"Going to Africa. Hope I don't get AIDS. Just kidding. I'm white!"

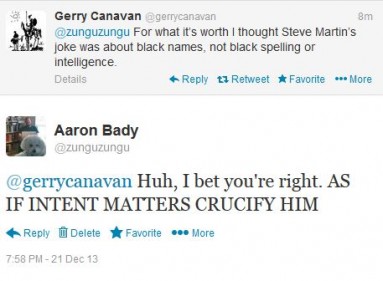

Why were these words sufficient to damn her to the hell of temporary internet infamy? As a useful comparison, last night,the comedian Steve Martin also made a joke that was, unquestionably, based in the racist premise that black people are stupid. But because he’s Steve Martin

Her tweet, on the other hand, was not very surprising; it wasn’t even all that offensive, at least not if we accept the premise that joking about racism is less offensive than making the serious statement that black people are jokes. What I mean is this: Steve Martin’s joke was simple minstrel theater, in which he was playing the straight man, the white guy that has mastered the English language and can, as a result, dryly observe the hilarious fact that black people have not. He is not the joke, in other words; they are. But part of the clusterfuck that was Justine Sacco’s tweet resides in the fact that she was exposing herself as racist, or at least pretending to, or trying to; she was trying to both be the joke and tell it, and it was her spectacular failure that became the spectacle. After all, Martin’s joke was that black people are less intelligent, ha ha. Her joke was more complicated; she said one thing and then also commented on it, not only making herself visible but making the break in her persona—between speaker and self-conscious viewer-of-self—the main thing we saw about her.

In terms of constative speech, I would suggest that what the tweet was actually saying—what she meant—was something like:

“The idea that only black people get AIDS—and white people do not—is something we’re not allowed to say, but I am a troublemaker, so I will say the thing that we are not allowed to say.”

In other words, the tension in the joke—that we relieve by laughing—is that you simply do not say that AIDS is an African disease. It is a taboo statement, precisely because it’s something that a lot of people actually, secretly believe, but feel precluded from openly saying, because, hmm, that sounds racist. Instead, you say something like:

“The AIDS epidemic is bigger than a tweet from a person in PR. If we want real change, we need to think beyond Justine. Let’s turn that anger into something tangible.”

My point is not that the people who set up that website are racist; it’s that they are speaking about AIDS in Africa in the good white person way

Steve Martin was performing the straight man, and doing what straight men do: provide the constative backdrop for the excessive and absurd foreground performance of the real object of humor, in this case, the minstrel spectacle of black people misusing language, hilariously unaware, etc. He gets it, they don’t, and so we see through his eyes, quietly judging their failures, and feeling the relief that we aren’t like that (a kind of disidentification, in fact; to get the joke proves that you are not the joke). But while his joke presumed that we see from his position—that we and Steve are a “we” together—Justine Sacco’s joke became a greasefire because she tried to perform both sides of the play, to be both the minstrel and the straight man, and because she was not there to re-establish order when the joke collapsed under the weight of that contradiction.

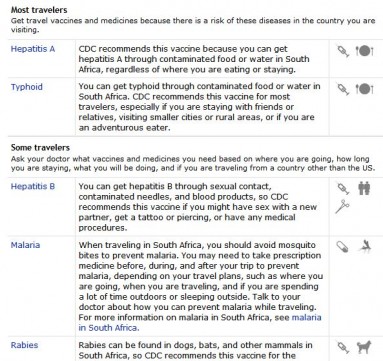

Her joke has three parts: a statement, a reframing, and an explanation. The first statement (“Going to Africa. Hope I don't get AIDS”) gets re-framed by the words “Just kidding,” which announce that what initially seemed serious—the basically rational desire to not catch a disease that can be fatal, on going to a continent where that disease is reputedly endemic—is actually not a real danger. A bit of context: when white people “go to Africa” they generally go to the doctor first, who tells them to get vaccinations and prescriptions against the various diseases that Africa has: pills for malaria, shots for rabies, etc. In other words, the first step, for most Americans going to Africa, is literally to get inoculated against the continent’s pathologies:

That there is no vaccination against AIDS is scary, if we accept the false premise that AIDS is essentially a contact disease, that one can catch it simply by being in an area where it is common (as one can get malaria by simply being in an area where infected mosquitoes are likely to bite you). Which is the mis-statement that the “Just kidding. I’m white!” corrects: going to Africa might put white people in danger of catching typhoid (because, as the CDC tells us “You can get typhoid through contaminated food or water in South Africa”) but being white protects you from getting AIDS, because, obviously, white and black people never have sex with each other. You cannot help but eat the food and drink the water, while you’re there, but you white people can avoid exchanging fluids with the natives, so you’re safe.

Is this racist? Of course, but boringly so: if the racist premise is that black people have AIDS and white people do not, then it only makes explicit what is implicit in a site like http://goingtoafrica.neocities.org/index.html; after all, if AIDS is the problem, you don’t have to go to Africa to find people dying of it. But Africa is a powerful story for white people because it allows us to heap a great deal of relief onto the spectacle of its misery: if AIDS is an African disease, then we can sigh with relief that we don’t need to fear catching it. And we can feel powerful and benevolent and in control; by merely clicking on buttons and donating, we can be part of the solution (For only 1 dollar a day, you can, etc.).

I am profoundly apathetic about Justine Sacco, herself; I find the whole spectacle fascinating, and hilarious, but that’s a separate thing from the actual Justine Sacco. If her career is ruined because she tweeted something really stupid, well, sucks to be fired, but that’s also the world we live in: capitalism means that when a business fires an employee, it’s not my business, literally. Capitalism also means that when an AIDS drug is patented by an American corporation, it cannot be copied and manufactured and distributed cheaply in places where the local economy does not support the high prices which an American corporation can charge. Drug patents mean that lots of black people die of AIDS because they either cannot afford the antiretroviral drugs that “we” in more highly developed economies can, or because the infrastructure for its delivery was never built (because, in the absence of profit, capital does not tend to market life-saving drugs). Drug patents are a tax on sick people. That’s not so simple as racism, even if centuries of racist violence and domination do have the result of making non-white people the primary victims of most forms of economic violence. But if we are upset that a capitalist enterprise exercised its right to make unemployed a person whose labor it had purchased—the basic right on which our entire economic system rests—then why are we not upset that drug companies exercise their right to prevent life-saving drugs from being put in the hands of sick people at the cost of their profits? It’s not our business to be upset about that; the business of the American people is business.

I want to suggest, then, that when or if we find ourselves sympathizing with Justine Sacco—suggesting that she should be shielded from the arbitrary punishment that capital enacts on labor that it no longer find useful—it’s because we are seeing through her eyes, taking on her perspective. We are realizing that we—and I would speculate that this is a very white “we”—can, if we say a thing judged to be racist, suffer consequences for it, even though we are, of course, not a bit racist.

We all say dumb stuff all the time; language (and especially humor) is a complicated and tricky business, and it’s easy to lose control over it. A tweet is not a window into Justine Sacco’s soul, and we all understand that. We have all had the experience of saying something that “was taken the wrong way,” a statement that seems innocuous to us—because we, of course, are basically good people—but which, in someone else’s perspective, seemed in some way hurtful. And if we cannot imagine ourselves being the arbitrary victim of racist, sexist, or homophobic mob violence, then the arbitrary workings of economic violence can seem like the real mob violence, because that’s the one we can imagine ourselves suffering from (because that’s the fear that haunts our dreams). So we sympathize with us, whoever that is. And sometimes, who we choose to think of as “us” has a lot more to do with who we want to sympathize with—and who we want to dis-identify from—than anything so unimportant as the question of whether someone you’d never heard of thought a racist thing.