Could we have kippers for breakfast,

mummy dear, mummy dear?

They got to have 'em in Texas,

'cause everyone's a millionaire

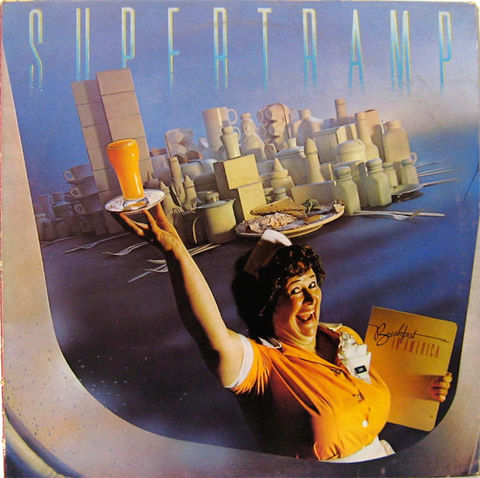

—Supertramp, "Breakfast in America"

I haven't spent much time in Texas, but I'm pretty sure that everyone there is not a millionaire. I never saw anyone in Texas or anywhere else in America eat kippers for breakfast. I'm not entirely sure what a kipper is.

Yet because I was at a vulnerable and impressionable age in 1979 when the English group Supertramp's "Breakfast in America" dominated FM radio, part of my mind has always clung to the idea that in Texas, there are millionaires eating kippers for breakfast. The very fact that I had no idea what that meant was exactly what made it alluring, aspirational. I wasn't sure if I would like to have kippers for breakfast myself (I could be finicky), but I definitely wanted to be the sort of person who knew why that was desirable. I wanted people to think I was eating them.

In my youthful naiveté, I saw secret and powerful knowledge in a line that was meant to convey Supertramp songwriter Roger Hodgson's own naiveté about America when he was young. Eating kippers for breakfast was something that happened in England, not America. Hodgson was trying to evoke what it was like to try to imagine the unimaginable — what life was like where I already lived. I was already living the unimaginable. Or perhaps it's better to adopt the terminology of another naivé interpreter of America, Jean Baudrillard, and say I was already deeply immersed in the hyperreal, in "simulations of simulations" that were "more real than real." There are no "real" kippers to have for breakfast, yet "kippers for breakfast" as an concrete idea, as something to sing and wonder about, is endlessly reproducible and served for me at least as a constitutive fantasy.

Baudrillard writes in America (1986): "There is a sort of miracle in the insipidity of artificial paradises, so long as they achieve the greatness of an entire (un)culture." Kippers for breakfast is that sort of miracle. An entirely implausible fantasy that is nonetheless perfectly characteristic. In America we want what we want when we want it, even if "we" never would consider eating a kipper. As Americans, we still expect to be seen as having anything anyone else could imagine wanting.

The point of being an American, as it is refracted back to Americans, is that you live in the most thoroughly stocked marketplace in the world, an efficient engine for realizing desires, imagination, experiences as products available to anyone who chooses to afford them. As Baudrillard contemplates the desert — perhaps a desert not unlike the rugged high plains of vast, sparse West Texas — Baudrillard comments that it is "a miracle of obscenity that is genuinely American: a miracle of total availability." In "Breakfast in America," Hodgson captures this same fantasy about American plenitude in the song's opening verse:

Take a look at my girlfriend,

she's the only one I got

Not much of a girlfriend,

never seem to get a lot

Take a jumbo across the water,

like to see America.

See the girls in California

I'm hoping it's going to come true

but there's not a lot I can do

In America, there is an overflow of eagerly available California gurls and an apparent promise of sexual abundance for every dismal, passive man bogged down in monogamy, even though there is "not a lot" he can do about it. The singer's dream of America seems to be that he will deplane from the jumbo and the women will throw themselves at him. That is what it means to him to "see America": consequence- and effort-free libidinous indulgence. He will become a perfect consumer who "gets a lot," who derives pure pleasure from sheer quantity of generic offerings, uncompromised by any specific appeals to him as a particular subject, as such hailings would also bring specific responsibilities. And in America, who wants that?

In other words, the fantasy of touring America, of conquering America, of becoming American, is a fantasy of losing oneself and being perfected in the hopeful consumerist melting pot as an exquisitely receptive pleasure sensor. Baudrillard writes, "The only question in this journey is: how far can we go in the extermination of meaning, how far can we go in the non-referential desert form without cracking up and, of course, still keep alive the esoteric charm of disappearance?"

This fantasy stems not only from America's colonial history as a catch-all for Europe's dissidents, heretics, and hustlers. It has more to do with its post-World War II climb toward global hegemony, as the Cold War exporter of freedom in the form of consumer choice and glamorized commodities — its movie stars and its blue jeans, inspiring the "children of Marx and Coca Cola."

But as the U.S. was beginning to send its McDonaldized way of life around the world with the rise of economic globalization, life within America was becoming ever more vertiginous, as American culture was situated at the vanishing point reflected in two mirrors pointed at each other. Growing up as an American meant trying to master that infinite regress, to take cultural hegemony in stride even as it spawned ambiguous forms of resistance in the zeitgeist, like Supertramp's homage. In part, it meant discovering one's own privilege in the distorting, mocking, and envying representations of it in entertainment products from abroad — products that Americans feel unabashedly entitled to appropriate. And in part it meant coming to terms with building an identity in line with America's apparent competitive advantage, which is in making seductive images and then quickly rendering them obsolete.

So Americans learn to know themselves in relation to ephemeral signifiers that tenuously have value attached to them, that can come and go like Supertramp did over the course of the summer of 1979. As the chorus of "The Logical Song," the other massive hit from Breakfast in America, put it, "I know it sounds absurd, but please tell me who I am."

On its face, "The Logical Song" is a pretty straightforward song about the disillusionment of coming adulthood, as one is forced to accept the reality principle and the "logic" of society's repressions and compromises. Wrenched from the childhood idyll in which "all the birds in the trees, they'd be singing so happily, joyfully, playfully, watching me," the singer is instead thrust into "a world where I could be so dependable, clinical, intellectual, cynical." This is the corollary of America as the land of libidinal plenitude: America as land of hyperrational calculation and alienated consciousness. Kippers for breakfast turn out to be a very different sort of pleasure than the jouissance of being at one with the birds who are watching you and singing to you, the pleasure of being assured of your belonging within the natural world. Banished to the desert of the hyperreal, one must banquet on ultimately empty signifiers, strategizing all the while how to consume more of them before it becomes meaningless in the eyes of others to do so.

I have lived in that desert, with its many mirages, and I've become too disoriented to find my way out of it. I still want kippers for breakfast, and if I didn't, I'd want something else impossible to nourish me. I don't think the birds were ever watching me, and if they were, I would have thought they were just jealous. I had the new Supertramp album on 8-track, and what the hell did they have?