You won't mind filling yourself in on the history baked into this dessert

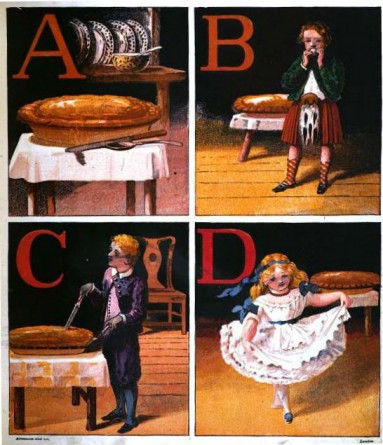

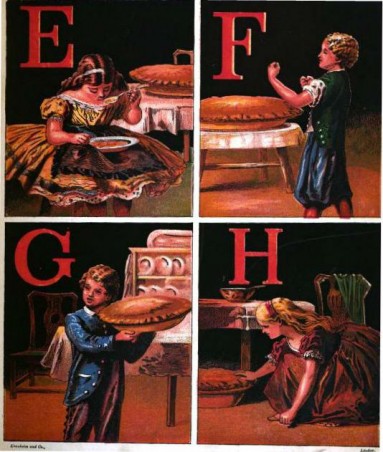

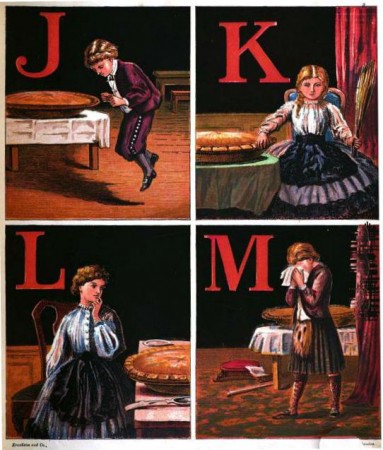

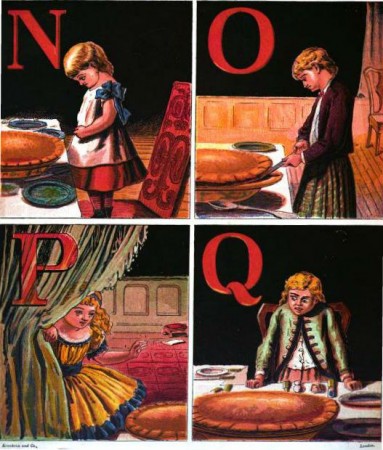

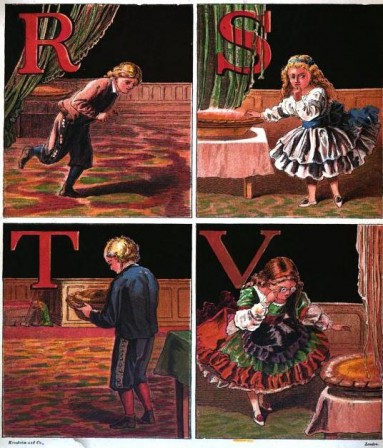

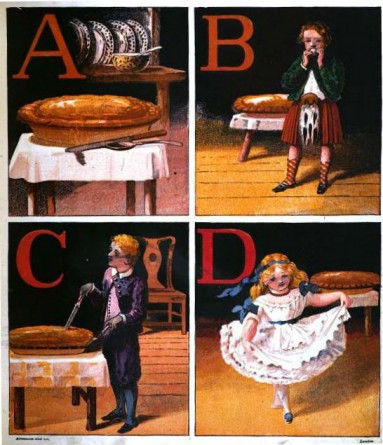

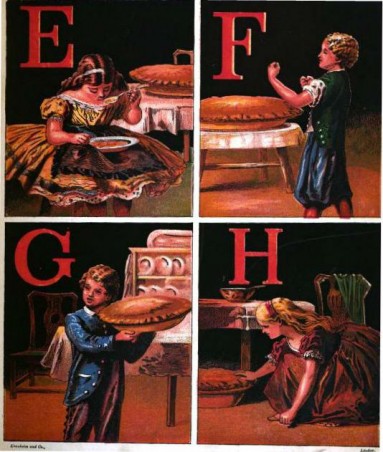

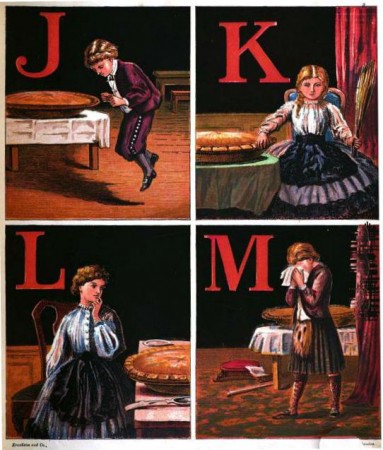

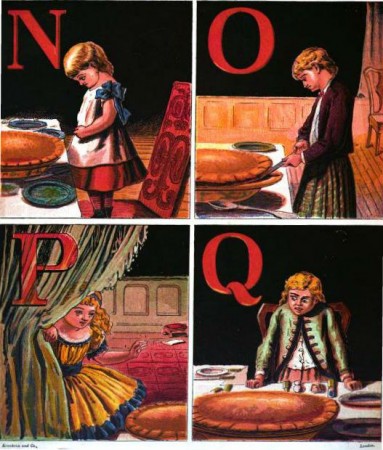

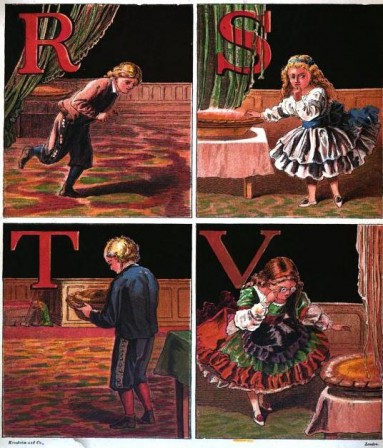

Illustrations from A. Apple Pie (1869)

During the nor’easter that descended on New England last week I spent many dull, rainy hours fixing a bicycle and baking pies. Fixing a bike has its charms. There’s a certain sense of accomplishment in taming a balky bottom bracket. But it's baking pies that I find more absorbing. It’s great fun seeing just how many foods can be transformed into dessert. At one time or another this past month I’ve sprinkled sugar over various fillings and packed them into inexpertly shaped crusts. Some pies have turned out better than others.

"Good apple pies are a considerable part of our domestic happiness." --Jane Austen

Apple pie, pumpkin pie, and even green tomato pie find takers when I give one away. Great northern bean and evaporated milk pie, however? Not so many.

I don’t take such refusals personally. People have always been suspicious of unusual pie fillings, which over the centuries have achieved an impressive variety. A flaky, golden crust could house anything from sprats to starlings.

"When first this infant Dish in Fashion came, / The Ingredients were but coarse, and rude the Frame; / As yet unpolished in the Modern Arts, / Our Fathers ate Brown Bread instead of Tarts; / Pyes were but indigested Lumps of Dough, / Till Time and just Expense improv'd them so." --Anonymous (ca. 1770)

Victorians stuffed their pies as eclectically as they did their homes. Those peddled by piemen ostensibly contained sausage meat, but few could link the filling to any barnyard animal. “Street pastry may be best characterized as of a strong flavor,” observed the Victorian sociologist Henry Mayhew, a quality he attributed to the presence of rancid butter. The servant Sam Weller of Dickens’s

The Pickwick Papers, however, thought that a purchased pie’s piquancy owed more to meow than cow. You should buy pie, he advised, only “when you knew the lady as made it, as is quite sure it ain’t kitten.” Similarly, journalist Albert Smith called street pies “covered uncertainties” and sympathized with the public’s secret misgivings “relative to the feline character of the Pie-material." In the United States, those misgivings extended to the flesh of another common pet. A popular tableau at lavish parties given at New York’s O' Dougherty House depicted a mock trial of a pieman accused of filling his pies with dog.

"From childhood we eat pies -- from girlhood to boyhood we eat pies -- from middle age to old age we eat pies -- in fact, pies in England may be considered as one of our best companions du voyage through life." --Alexis Soyer

The worst rumor of all circulated in 1824. It concerned a most unusual Parisian barber and wigmaker. He plied his trade on the rue de la Harpe, next door to a baker whose meat pies were astoundingly popular among the wealthy. It wasn’t long before it was noticed that the barber’s clients entered his shop but never exited. Not soon after, an investigation by the chief of police uncovered a plot in which the barber, under the pretense of giving his clients a close shave, slit their throats, stole their valuables, and then passed their bodies along to the baker to be transformed into delectable pies.

From this story came inspiration for the character of Sweeney Todd in The String of Pearls (1846-7).

A search of his basement revealed the bones of hundreds of men, the flesh of whom had long since filled the bellies of Paris's upper crust.

"Lunch was $6.31 at the Lamplighter Inn. That's on Highway Two near Lewis Fork. That was a tuna fish sandwich on whole wheat, a slice of cherry pie and a cup of coffee. Damn good food. Diane, if you ever get up this way, that cherry pie is worth a stop." --FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (ca. 1990)

"There is no being more easily distinguishable at a glance than the pieman: the plumpness of person, which is his invariable characteristic, would expose him to a whole world of prying observers: his rotundity of shape differs very materially from that of other men ... the pieman is plump and gross -- lusty but not corpulent; but his fair round belly does not seem to be crammed with too many of the good things of life; his appearance betokens a man quite at his ease; fattening, as it were, upon his guilt; he is not like pasty -- 'puffy:'-- his rotundity is solid -- it differs from the rotundity of other men -- it is the rotundity of 'the pieman.'" --from The Casket (1828)

Morbid conjecture of this sort made for a volatile market. Few would envy a London pieman, as he wended his way, pie-can in hand, through the damp, dark streets, crying, “Pies all ‘ot! eel, beef, or mutton pies! Penny pies, all ‘ot! -- all ‘ot!” On a good day he might sell 240 pies; on a bad, none at all. “I was out last night from four in the afternoon till half-past twelve,” complained one pieman, “and I didn’t take home 1 shilling 6d.” Ready custom could only be found in the drinking houses. There working-class men, tipsy with ale and numb from the day’s employment (or unemployment, as was often the case) waited for the pieman to appear. With his cry of “Here’s all ‘ot!” commenced a popular game. He would flip a shilling coin and invite someone to call it heads or tails. Calling it correctly won the caller a free pie. Calling it incorrectly won him the pieman’s outstretched hand and expectant look.

The Cook in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales is challenged to tell his own story to atone for serving reheated pies: “And many a Jakke of Dovere hastow soold / That hath been twies hoot and twies cold.”

During the middle ages and into the early modern period, mystery pies were sought rather than shunned. People then loved unusual surprises. They made their pies large and unwieldy and painted them brightly with pigments derived from lead oxide, metallic mercury mixed with the “pisse of a young child,” and arsenic mingled with hare bile and buried under a dung heap for five days. From these gaudy “coffins,” as they were called, issued canaries, frogs, and people. When in 1626 the diminutive Jeffrey Hudson

Hudson stood two feet tall.

burst from a pie before Charles I and his wife Henrietta Maria, he so delighted the royal couple that they made him a permanent member of their household. Bridal pies too were filled with sundry surprises. Robert May includes a recipe for one in his

Accomplish’t Cook (1671). It calls for oysters, dates, pine kernels, barberries, marrow, prawns, cockles, artichokes, cheese, garlic, larks, and heaps of spices to be stuffed into six or seven tiers of pastry. And if those ingredients weren’t enough, May suggests tossing in “live birds, or a snake” to “pass away the time.”

"Rather than fail they will decry / That which they love most tenderly; / Quarrel with minc'd pies, and disparage / Their best and dearest friend, plum-porridge, / Fat pig and goose itself oppose, / And blaspheme custard through the nose." --Samuel Butler

Medieval monuments of pastry were for the most part savory. Sweet pies didn’t appear with any regularity until the 16th century, when sugar became more widely available.

During this period, pies made in the sweet-sour tradition and featuring such disparate ingredients as eggs, sausages, marrow, grapes, dates, and barberries were also popular.

American colonists made an art of the sugared fruit pie. Yet their seemingly innumerable recipes for apple, pumpkin, mince, and custard pies were more or less conservative; of a puritanical bent, they deemed devilish anything more. The British also began to incline toward sweeter pies during this period. Queen Elizabeth I delighted in pies of candied orange peel, and with some regularity her subjects baked ones filled with heavily sweetened meat, fruit, and vegetables.

Pies remained quite variegated until the 20th century, when the scientific revolution’s mania for taxonomizing and classifying came to apply even to baked goods.

Recipe for "Mince Meat for Pie" from The "Home Queen" Cook Book (1901): "Shred and chop very fine 2 lbs. beef suet -- by dredging the suet occasionally with flour it chops more easily and does not clog -- boil slowly, but thoroughly, 2 lbs. learn round of beef and chop fine (mix all the ingredients as they are prepared), stone and cut fine 2 lbs. raisins, wash and pick 2 lbs. currants, cut fine 1/2 lb. citron, chop 2 lbs. apples -- weighing them after they have been peeled and cored -- a table-spoon salt, a tea-spoon ground cinnamon, a grated nutmeg, a salt-spoon allspice, 1/2 as much cloves, 1/2 oz. essence of almonds, 1 pt. brandy, 1 pt. cider. This may be kept in a cool place all winter. If too dry add more cider."

Janet Clarkson begins her

Pie: A Global History (2009) with an account of a debate that appeared in the

Times of London.

In 1927, a Mr. R.A. Walker wrote a letter of “vigorous protest” decrying the “abominable soul-slaughtering and horrible trick of serving puff pastry and stewed fruit under the guise of apple tart. This was answered by one Col. John C. Somerville, who promptly took Walker to task for using “apple pie” and “apple tart” interchangeably. “All properly brought up children,” he added, would know the difference. By his lights pie was “whatever is cooked in a pie dish under a pastry roof.” The newspaper’s readers apparently dissatisfied with this response, the debate raged on, fueled, Clarkson writes, by “veiled insults ... categorical statements ... and side issues.”

Present-day disputes over pie tend to be far more diplomatic. Cookbooks feature recipes for pie alongside those for pastries and tarts, and no undue criticism ensues. Yet like our colonial forebears, we continue to take a conservative view of filling. I have yet to see a beet pie in a commercial bakery, though I understand they’re delicious. And my bean pie sits in the refrigerator untouched. I guess the Roman writer Publilius Syrus was right when he wrote, "The most delightful pleasures cloy without variety."