Since Robin Gibb died last Sunday I have been listening a lot to the Bee Gees. Given the magnitude of their “third fame,” after the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack seemed to temporarily change everything about culture, the group is sometimes mistakenly regarded as nothing more than falsetto-wielding disco appropriators. But before that, the Bee Gees had a long, successful career as Beatlesque balladeers with a penchant for surreal whimsy and songs suffused with a melancholy so pure it becomes almost abstract.

Their material from the late 1960s and early '70s, especially, is unabashedly fixated on loneliness and weeping, and the words lonely and crying recur with a mantra-like regularity. A cynic might suspect they had adopted the words as lazy emotional shorthand in lieu of sincerity, as if that means anything in the context of pop music. “For once in my life I’m alone,” “I started to cry, which started the whole world laughing,” “Run to me, whenever you’re lonely,” “Lonely days, lonely nights, where would I be without my woman?” “I am alone again, you can’t believe the tears I have shed.” This tendency reaches a kind of apotheosis with the 1972 single “My World,” less a song than a relentless sentimentality machine.

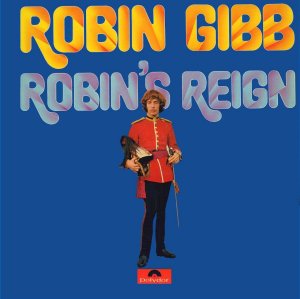

No one conveyed loneliness quite like Robin Gibb, whose eerie, inimitable voice seemed uniquely calibrated to convey inconsolable sadness. If you want to overdose on his forlorn quaver, you can listen to his 1970 solo album Robin’s Reign,

which is filled with baroque dirges, but the bridge of "My World" boils his approach down to its stark, vulnerable essence: "I've been crying. I'm lonely. What do I do to have you to stay?" In the clip above, he does his trademark pose, hand over his ear to stay in tune as he warbles these lines, naked in their directness, shamelessly needy.What kind of metaphor can suffice to express that kind of loneliness? The song's chorus inflates it to the size of the universe: my world, our world, this world, your world. The Gibbs' voices metronymically tick off these permutations in seemingly effortless harmony, and if you weren't paying attention, you might not realize that the song is not a hymn to shared togetherness but the opposite. Basically, there is nothing effortless about any kind of harmony. All those posited worlds are desperate combinations trying to unlock the smothering solitude. Nothing works but the plea, the confession, the celebration of hurt: "I've been crying. I'm lonely."

Robin has lots of these moments scattered throughout the Bee Gees' records where he puts his voice at odds with the comfortable, professional songcraft and the lulling orchestrations, troubling it all with a trembling emotionality that exceeds all causality. My favorite example comes in "It Doesn't Matter Much to Me," a 1973 track from the shelved album A Kick in the Head Is Worth Eight in the Pants. Barry sings a forceful, almost ill-tempered verse about refusing to accept a breakup, but then Robin delivers a chorus in an unhinged voice that makes it seem silly to try to figure out what the song is "about": "It doesn't matter much to me, baby I've been hurt before." The title is irresolvably ambiguous; we can't really tell what "it" is that is not supposed to matter. Robin's vocal suggests that whatever it is, it actually matters a great deal. It sounds as though nothing matters more than the fact that he's been hurt before, and at the same time it doesn't matter at all since he is always hurt. It's the default condition. The disproportionate intensity of his delivery tells us that there is no "before" hurt, no after hurt; there is only hurt, but at least it is not impotent. It can cry out impossible yearnings for solace. Unlike the numbness of depression, the song offers the hope of intense feeling surviving stasis.

What all this crying and loneliness in the Bee Gees' music promises is that there is no consolation in denying it, and no point in trying to come up with arch ways of disguising it or revealing it, as if that would make sadness more tractable. One of their early signature songs, "How Can You Mend a Broken Heart," makes this plain. The question is not answered but followed with a bunch of other deceptively simple rhetorical questions:

How can you mend a broken heart?

How can you stop the rain from falling down?

How can you stop the sun from shining?

What makes the world go round.

Okay, we get it. Maybe mending a broken heart is just impossible, a favorite Bee Gees thesis. It just lingers like a perpetually open wound.