Leandro Velasco, The Gift (1976)

This is an extended mix of a piece I published elsewhere.

Once upon a time a mix tape spent three weeks getting made by a boy in Texas.

The tape’s intended recipient (yours truly) received it in a melon-yellow, padded envelope ornamented with hearts scrawled in blue ballpoint. Along with it came four small bars of hazelnut milk chocolate (grown soft from the July heat), and, in cramped black writing scratched on a page ripped from a Mead notebook, the story of its production.

An entire week, the note explained, the boy in Texas spent finding, then altering with lavender-colored pencil and white-out, a blurred photocopy of a photo of a four-car pileup on the A-47 that first appeared in Paris Match. This he carefully trimmed, folded in eighths, and slipped behind the cassette’s brittle plastic case. It took another week to decide if The Stone Roses’s “I Wanna Be Adored”

Of the Theban musician Ismenias, Atheas, King of the Scythians, declared he liked his music "better than the braying of an ass."

should precede New Order’s “Ceremony” or vice versa, and if the final song on side B should feature the original or a cover of The Doors’s “Hello, I Love You.” The third week he confessed to wasting in dithering over whether the cover at all suited the tape's contents, whether he erred in leaving off Echo and the Bunnymen’s “All My Colors,” and whether our dial-up romance, which had blossomed so beautifully in an AOL chat room, would wither despite his gift of one perfectly sequenced bit of sonic sentiment.

The epistolary affair did wither (as do all passions in a fickle fourteen-year-old heart), and the Texan’s tape rests

"A correct comprehension of external, material things is a preliminary to a just comprehension of intellectual relations." -- Friedrich Froebel

in a musty corner of my closet, its viscera exposed and tangled. For a brief time that delicate strip of metal oxide I did treat as an emblem of my lonely adolescence. So carefully dubbed and packaged, it came as a great honor to have received it. I made as many mix tapes as I had made for me. I gave them for every occasion, under the influence of every caprice. Crouched before the household Kenwood rack system, I made tapes for those I wished to convert to my musical tastes, and for those I had converted. I made tapes for lonely 2:00 AM drives on the freeway, and tapes for happy mid-afternoon jaunts to the record store. I made “I love you, you’re just like heaven” tapes, and “You’re cool, but I just want to be friends” tapes.

Hither and yon these tapes traveled, to cities as disparate and far-flung as Iuka, Kansas, Pensacola, Florida and Manchester, England. I made no two exactly alike. Some sported elaborate cover artwork, while others merited only a hastily scribbled song list. Song sequences varied according to my mood, which went from exuberant to morose at the drop of a hat. Each tape bore the stamp of its moment of production, containing not only the crooning of Morrissey or Robert Smith, but all those unspoken, confused, tumultuous thoughts of an adolescent whose awkward isolation more eloquently communicated itself through the creative act of dubbing than through speech. More than a gift, the mix tape I considered a document whose unprepossessing, mass-market exterior belied its contents: a high-fidelity analogue of a teen's deep and complicated interiority.

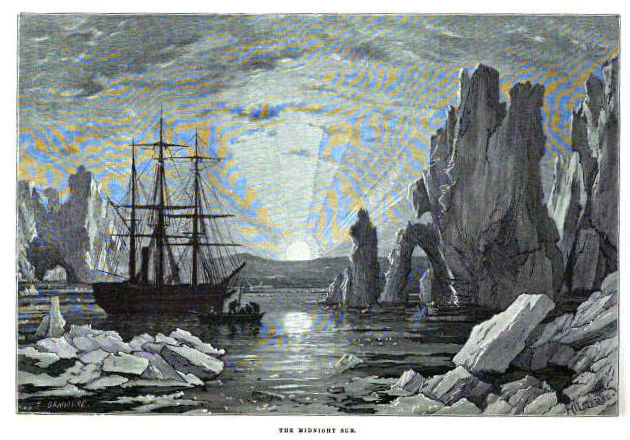

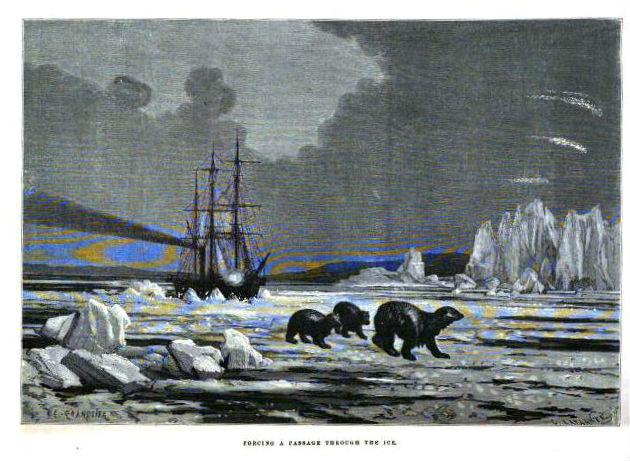

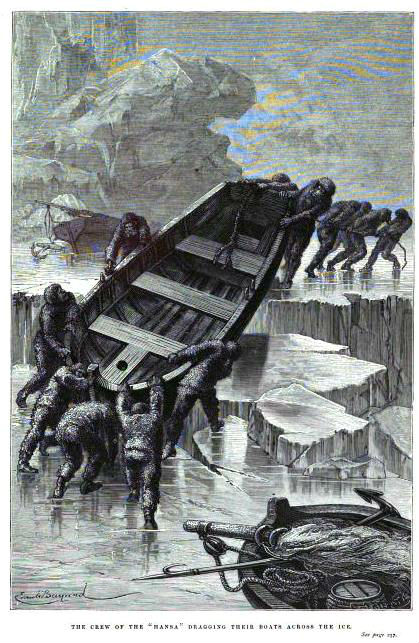

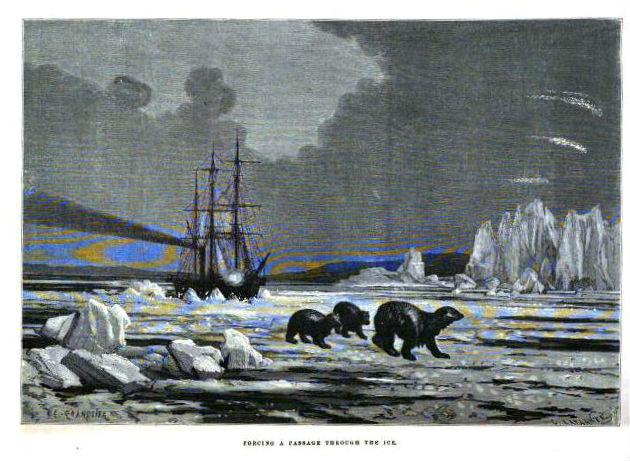

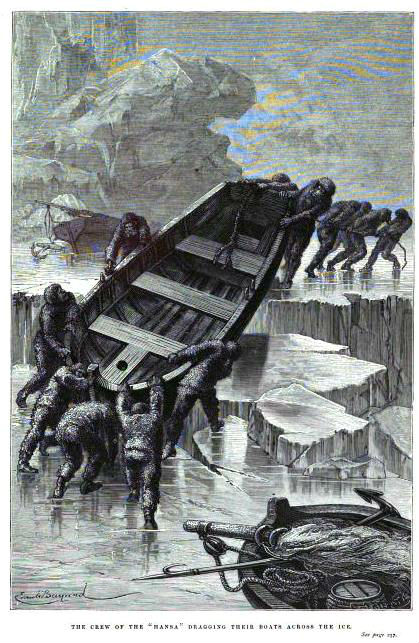

Illustrations from William Henry Davenport Adams's The Arctic World (1876)

So intensely did I experience my loneliness that I often imagined myself as if adrift on the high seas. Indeed, when making mix tapes or chatting online didn't occupy me, I read stories of sea voyages. I liked best accounts of Arctic travel -- the more disastrous, the better. There seemed no greater desolation than that of a whaling crew fixed fast in a sheet of ice that spanned horizons. I thought somehow this plight mirrored my own as a pasty emo girl marooned in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Indeed, nothing says "desolation" like the Arctic. "Your sense of loneliness also heightens the effects of the Arctic seas," notes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In 1880 he had volunteered as a surgeon aboard a whaling ship. The voyage he had found for the most part exhilarating; the Arctic wastes, however, had unnerved him. "When we were in whaling latitudes it is probable that, with the exception of our consort, there was no vessel within 800 miles of us. For seven long months, no letter and no news came to us." Doyle later admitted that the experience of such unremitting isolation haunted him his entire life.

Other Arctic voyagers remarked on the remoteness of the frozen wastes. Their immense size stupefied these early explorers. Journalist William Henry Davenport Adams estimated that the Arctic "comprises an area of 2,500,000 square miles." This "immense portion of the terrestrial surface" had effectively "shut [itself] out from the knowledge of Civilized Man." A more apt description Adams could not have given it; its inhospitable nature seemed to repulse all attempts at coming to know it. Though sometimes the sea around floes lay as still

"Dead Water. The eddy-water closing in with the ship's stern, as she passes through the water. It shifts its place, but is like taking money from one pocket and putting it into another." -- Dictionary of Phrase and Fable

and smooth as glass, it often roiled and seethed, and ice formations called growlers, which could fatally cleave ship hulls, floated just below its surface. Other chunks broke off from shoreline glaciers, plunging without warning into the water below. Thick mists that glittered like diamonds hid behind them rocks and other dangers.

"It is no fun, I assure you, to sit noiseless and motionless, with a cold iron musket in your hands and the temperature 10 degrees below zero," writes Dr. Elisha Kent Kane on hunting the Arctic seal. "Very strange are these creatures. They have a countenance between a dog and an African ape, and an expression so like that of humanity that it makes their murderer hesitate. At last I hit one. God forgive me!"

Landfall on this alien shore proved tricky, and ships that arrived in summer could count themselves lucky. In this season the Arctic charms as much as it perplexes. The midnight sun hangs in the sky like an insomniac's lamp and imbues the icebergs and snowdrifts with a rosy glow. In the shadow of these great masses the water glimmers green like malachite. Further inland small tufts of grass and pale purple flowers stipple rock-strewn plains. Great conifer forests shelter reindeer, who roam and browse on lichens, and in gelid blue-black lakes salmon and sturgeon gather to spawn. Against the sky birds spin and whirl their way to riverside nests, where downy hatchlings await their succoring slurry of regurgitated fish. Life in its infinite variety (save that of man) thrives during these brief halcyon days.

Winter landfall met with a different scene altogether. Then silence greets the Arctic explorer, as does the sharp tang of ubiquitous snow. No rosy glow issues from the sun; the winter sky

"What Froude says of history is true also of astronomy: it is the most impressive where it transcends explanation." -- Garrett Putman Serviss, Curiosities of the Sky (1909)

looms dull and dark. "The grave of Nature, containing only the bones of another world," Adams described the Arctic winter. The change in season did transform the tundra into something otherworldly. "The people, and even the snow, throw off a continual vapor; and the evaporation is instantly changed into millions of needles of ice, which make a noise in the air like the sound of torn satin or the rustle of thick silk," Adams continues. "The reindeer take to the forest, or crowd together for heat; and the raven alone, the dark bird of winter, still smites the frosty air with heavy laborious wing, leaving behind him a long trail of their vapour to mark the course of his solitary flight.... The atmosphere grows dense; the glittering stars are dimmed."

Under those dim stars, the winter ice could trap a ship for five, six months -- sometimes longer. Surrounded only by an endless sweep of snow

Livy notes that when Hannibal led his army over the Alps to enter Rome he used vinegar to dissolve the snow and make the march less slippery.

and ice, sailors had to devise amusements to pass the weeks and months. This they did with great inventiveness. The sailors staged carnivals, with pubs, dance halls, and even barmaids carved of ice. At night they regaled one another with tales of adventure on the high seas. Braver souls set out to explore the wastes, traveling great distances and returning with news of the strange and wonderful tribesmen who make the ice their home.

"Throughout the Pacific, and also in Nantucket, and New Bedford, and Sag Harbor, you will come across lively sketches of whales and whaling-scenes, graven by the fishermen themselves on Sperm Whale-teeth, or ladies' busks wrought out of the Right Whale-bone, and other like skrimshander articles, as the whalemen call the numerous little ingenious contrivances they elaborately carve out of the rough material, in their hours of ocean leisure. Some of them have little boxes of dentistical-looking implements, specially intended for the skrimshandering business. But, in general, they toil with their jack-knives alone; and, with that almost omnipotent tool of the sailor, they will turn you out anything you please, in the way of a mariner's fancy." -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

One of the most popular Arctic amusements was also the simplest. From whales' teeth and bones sailors carved delicate novelties called scrimshaw. First seen on whaling ships

"I have seven ships upon the sea, / Laden with the finest gold, / And mariners to wait us upon; -- / All these you may behold. // And I have shoes for my love's feet, / Beaten of the purest gold, / And lined wi' the velvet soft, / To keep my love's feet from the cold." -- From the ancient ballad "Fragment of the Daemon Lover"

around the mid-eighteenth century (though the practice predates this period), scrimshaw came in many forms. Pie crimps upon whose handles perched sloe-eyed, wild-haired mermaids; combs etched with sea shells and yapping seals and decoratively stained with tobacco juice and soot; sea monsters that encircled yarnwinders -- these and other depictions sprang from the sailors' marriage of fancy and skill. The most elaborate scrimshaw betokened the deepest intimacy. Long strips of whalebone, two to three inches wide and about a foot long, sailors decorated with winding roses, trailing vines, initials and loves mottoes, all usually encircled by intertwined hearts. These strips women would slip into bodices to hold them tight. Known as busks, they reminded the wearer of her seafaring swain.

Sailors made scrimshaw not only to while away the hours, but also to bridge two worlds, the maritime and the domestic. The designs reveal as much. The fantastic world of the sea, all its peculiar creatures and monsters, they etched into tools intended for housework. By doing so, sailors forged a connection to loved ones seemingly on the other side of the earth. In his story "Christmas in the Arctic Regions" (1876), J.H. Woodbury describes the predicament of a group of sailors "frozen in" the Arctic circle. In this dreary land they must pass "one long winter night for months, unbroken by a rising sun." Rather than despairing, however, the sailors set themselves to carving. "I don't think you will find scrimshawing in the dictionary," Woodbury's narrator informs readers, "for the word isn't used much on shore." Woodbury has one sailor explain that the term means "cutting, etching, scratching, carving--making all sorts of pretty things out of whalebone." This same sailor offers a sense of his and his shipmates' output: "We had made jagging-knives, and things to keep the girls straight and things which we had no names for." Only seafaring sorts took to whittling whales' teeth, which, though expressive of acute longing for home and loved ones, resulted in objects so singular that their existence preceded their application.

Their uniqueness made scrimshawed items coveted gifts. New England wives compared their collections to see whose husband had put the most effort in his work; the more elaborate the carvings, the more devoted the husband. An 1852 edition of The Journal of Agriculture features a story in which the narrator describes an old scrimshawed pipe, "the gift, long ago, of a favorite uncle, a sea captain, 'whose bones have bleached these many years in some deep cavern of the sea.'" This pipe the family treats with great reverence. "Its capacious bowl was never polluted by contact with the poisonous weed, nor its ivory mouth-piece desecrated by lips profaned with its touch." So unique is this whalebone pipe that the captain's kin dare not employ it for its intended purpose, a prohibition buttressed by knowledge of its maker's having since descended to Davy Jones's locker.

"Meals were served at 7:30 A.M., at noon, and at 5 P.M.," observes John Randolph Spears in The Story of the New England Whalers (1908). "Meat usually boiled, and bread were dumped in bulk into pans and carried from the galley, or cook room, to the forecastle, where the men divided it and ate it from small pans. For drink they had tea and coffee sweetened with 'longlick' -- molasses."

"A group of men so undesirable that they have been dismissed from the Army are hardly more desirable in a civilian community.... If these men can be put through a vigorous medical examination on their return, all possible abnormal conditions corrected, occupational therapy ... given as necessary, these men ... might be made serviceable." -- From "Training of Teachers for Occupational Therapy for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Soldiers and Sailors" (1918)

Born of its maker's circumstances, scrimshaw documents for those far away the seagoing life and its particulars -- the whaling ship, fish-scented and cold; the white immensity of ice; the dark, dull winter; the crushing isolation. Simple gifts carved from teeth and bone, they exemplify what sociologist Michel de Certeau

The Practice of Everyday Life (1984)

calls acts of "everyday creativity," which help to elevate us above adverse circumstances. The creative act, usually some type of unalienated material labor (sewing, drawing, writing, cooking, etc.), frees us from the constraints of a society dependent on incessant getting and spending. Within the context of the whaling ship, the act of scrimshaw allowed sailors to articulate inchoate experience through craft and, by doing so, transcend, at least imaginatively, their isolation. Out of this act came a gift in the truest sense, one which cannot be reciprocated; for in those combs and pipes the giver objectified the contents of his individual experience.

Though life today militates against devoting time to painstaking creative acts, the mix tape stands as a vestige of everyday artistry. Cobbled together from found cultural objects, it like scrimshaw embodies an individual's experience of the world. As such, it achieves as much authenticity as any carved bit of tooth or bone. One mix tape, given to me for my fifteenth birthday by an alcoholic second cousin, I keep in the top drawer of my desk. It’s a white, off-brand tape. Across its top in tremulous cursive it reads “Christine’s Songs.” It boasts a motley mix, everything from Style Council (she dated the band’s drummer Steve White) to The New York Dolls (she dated singer David Johansen as well) and The Ramones (she once sold Joey Ramone a saxophone). Generally she proved a deft hand at recording mix tapes. But between Wire’s “Dot Dash” and Love Tractor’s “I Broke My Saw” there appears on the tape I have from her thirty seconds of faint cursing, the barking of a nervous spaniel, and the creaky complaint of buttons half pushed as she attempts to set the machinery right again -- a brief audio document of well-intentioned clumsiness on a tape now some fifteen years old from a person I once thought wonderful and with whom I’ve since fallen out of touch.

I don't know if we still give one another such gifts. I feel, though, that if we don't, we should. The illusions of digitally mediated community that we find foisted on us only engender an isolation as vast and oppressive as any Arctic waste. To bridge this gulf, we must look to older ways of connecting with others. For despite our increasingly virtual world, the material gift still enjoys tremendous currency as means by which we can express things that lie too deep for tears -- or 140-character tweets.