Illustrations from Le Diable à Paris (1868)

"Sleep is the interest we have to pay on the capital which is called in at death; and the higher the rate of interest and the more regularly it is paid, the further the date of redemption is postponed." -- Arthur Schopenhauer

Those winter nights on which Benjamin Franklin couldn't get to sleep, he'd hop out of bed, open the windows, turn down the bedclothes and wait until both they and he were thoroughly chilled before climbing back in.

Franklin attributed troubled sleep to an accumulation of body heat. Rest for him was a dish best served cold. His thinking on this matter accorded with contemporary scientific theories. Yet the founding father's approach to insomnia was likely the exception rather than the rule; most people at the time looked to less complicated remedies.

Said Iago to Othello: “Not poppy nor mandragora, / Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world, / Shall ever medicine that sweet sleep / Which thou owest yesterday.”

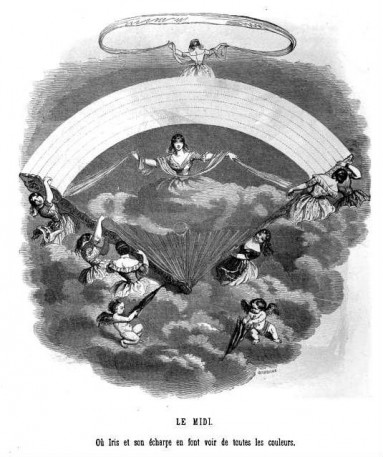

Johann Christoph Sauer’s

Compendious Herbal, one of mid-eighteenth century America's most popular medical references, recommended mixtures of Florentine iris or elderberry blossoms steeped in milk to induce sleep and drive away nightmares. Thyme was thought to soothe the brow plagued by unpleasant dreams. Indeed, the treatments at hand were seemingly endless: Valerian, skullcap, wild lettuce (a favorite sleep aid of the Greco-Roman physician Galen), catnip, hops, chamomile, lemon verbena -- all possessed sleep-inducing qualities. Only when home cures failed to work did families look to traveling drug peddlers, who sold more potent medicine.

Franklin's Philadelphia teemed with such peddlers. They represented local drug firms, and along Chestnut Street, near Independence Hall, they would parade, crying, “Sassafras! Bergamot! Sweet Basil! Wormwood!” If they failed to find trade enough in the city, they sought customers in the backwoods, carrying their nostrums and elixirs with them. Writing a few decades later, Nathaniel Hawthorne recalls meeting one such salesman, “a Dr. Jacques, who carried about with him recommendatory letters in favour of himself and drugs, signed by a long list of people.” Hawthorne quickly sized up the hawker of dubious wares, observing, “I believe he comes from Philadelphia.”

“We are slumberous poppies, / Lords of Lethe downs, / Some awake and some asleep, / Sleeping in our crowns. / What perchance our dreams may know, / Let our serious may know." -- Leigh Hunt, "Songs and Chorus of the Flowers: Poppies" (1836)

The city was synonymous with quack medicine, and rightly so. Opium figured prominently in the soporifics peddled. But opium's use had a long and storied history. A prominent English author of seventeenth-century medicinal manuals recommended a syrup made from black poppies for “frensies, or to those that are restless, and cannot sleep well.” Before bedding down on a heap of hay likely shared with a sheep or two, peasants mixed a sleep-inducing concoction of sugar and poppy seeds, which they wrapped in linen for their restless children to nurse.

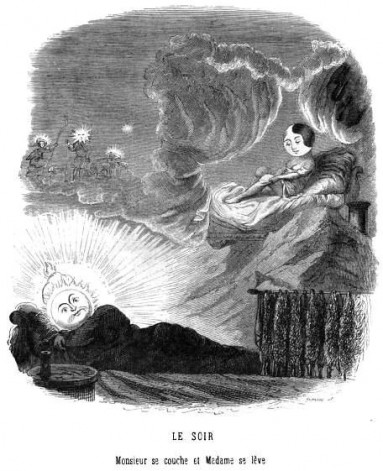

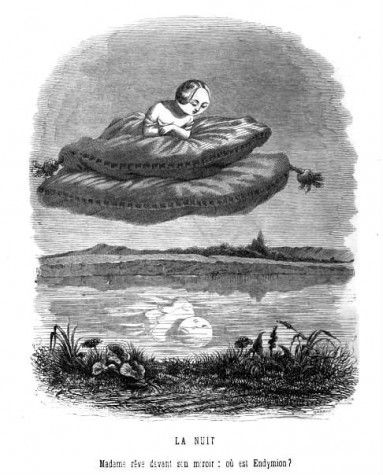

The Romans imagined Sleep as maintaining a stately residence. Accessible by five gates -- Rest, Ease, Silence, Indolence and Oblivion -- his palace consists of basalt columns as dark as night, marble walls inlaid with jet-black stones, great chambers, and innumerable arches vaulting into the gloaming. Murmuring fountains, encircled by tufts of poppies, mandragora and other soporific flowers and herbs line the hall, at the end of which Somnus rests on a couch strewn with poppy petals. By his side dozes a lion, on whose shaggy head he drapes his arm. In his other hand, he holds a fragrant horn of poppy juice, which, in his slack grip, tilts and drips its contents onto the marble floor.

Ancient Greeks and Romans likewise used poppies to ward off insomnia. Pliny the Elder claimed the word “poppy” (

Papaver) derives from

papa, meaning “pap,” the standard food of infants, to which nursemaids added poppy juice to induce sleep. The ending -

ver comes from

verum, meaning “true.” Poppies the ancients considered the true sleep-producing substance. And like their later counterparts they knew that too much poppy juice stupefied rather than lulled. The Roman physician Caelius Aurelianus remarked that wanton use of soporifics brought on daytime lethargy and were as likely to ferry the sleeper off to Xanadu as to the Land of Nod.

Perhaps keeping Aurelianus's warning in mind, medieval men and women were more temperate in their use of soporifics, often preferring the grape to the poppy. Before retiring, lords and ladies drank the “wine of repose.” This sweet, calming draught, usually a mixture of wine, honey and spices (though burnt wine and hippocras also proved popular), a squire served after dinner. Guest and lord quaffed it throughout postprandial entertainments, enjoying its intoxicating effects well into the night. While undressing for bed royals sipped more, so that by the time they slipped between the sheets one could imagine they were sufficiently woozy. If they happened not to be, jesters stood by to sing and whisper tales until the drink took effect.

Recipe for Punch Royal from Oxford Night Caps: "Extract the juice from the peeling of a lemon, by rubbing loaf sugar on it. Pour one pint of boiling water on it. Add the juice of six lemons, one pint of rum, and a pint of port wine. Sweeten it to your taste, and it is fit for use."

Tippling

was likely the most effective and enjoyable way to combat sleeplessness. Or so thought a group of raucous Oxonians, at any rate. In 1835 the slim volume

Oxford Night Caps: Being a Collection of Receipts for Making Various Beverages Used in the University appeared. But if the book's recipes summoned the Sandman they did so only to get him so drunk on such alcoholic delights as perry cups and beer flips and pepper possets that he would forget his duty. The book proved popular among students. It remained in print for over a century, leaving one to wonder if even the rather ascetic Ben Franklin wouldn't have preferred a steaming bowl of lemon punch to eight hours in a frosty bedstead.