What happens when Kenyan women say that we want to stop being hurt again and again and again?

Ideally, we would be taken seriously: victim naming-and-shaming would not happen; sexual violence apologia would not surface; perpetrators would be held accountable; and men would finally stop hurting us.

One would hope. But our upbringing is fraught with stories about the consequences that un-silent women faced.

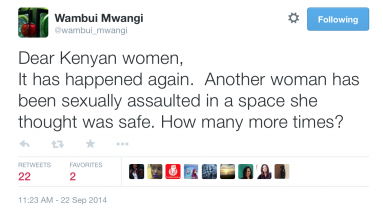

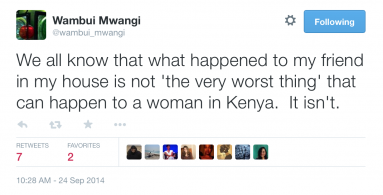

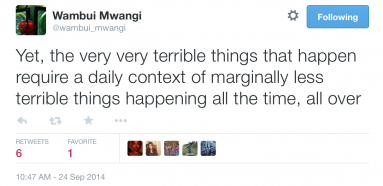

On Monday, 22nd September, Professor Wambui Mwangi announced on Twitter that Kenyan writer Tony Mochama had entered her home and allegedly sexually assaulted another writer and a good friend of Prof. Mwangi’s. The backlash was immediate. Kenyans on Twitter and Facebook wanted to know who the victim was, where she was touched, why she was staying silent about it, and why the accusation had been brought to social media instead of being taken to the police.

Responding to this backlash, Shailja Patel bravely came forward, identifying herself as the victim.

Despite there having been witnesses, Mochama first declared he had not even been at the house, and then that he had been there and had been told to back off from giving Shailja Patel a hug. In a later interview, Mochama said he did not once go near Shailja Patel.

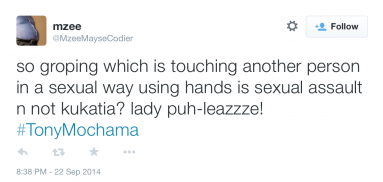

Kenya’s Sexual Offences Act (2006) calls what Mochama allegedly did an “indecent act.” One man called it “kukatia”—flirting. Kenya’s gutter press decided to call it “rape”.

What happens when Kenyan women refuse to be silenced?

When women are muted, they are dehumanised. That thing which is silent cannot be hurt. That thing which is silent cannot know anything. That thing which is silent can easily be considered non-existent.

But Kenyan women are refusing to shut up. We have fought for years to make our horror heard and felt in Kenya’s collective imagination.

To force us back into silence, Kenyan men continually take over the narrative of gender-based violence.

They trivialise it.

They call it ‘kuchotwa.'

Kuchotwa sounds like petty larceny, or like the auctioneers have come to collect something.

They normalise it.

What is the difference between date rape and other kinds of rape?

“Not much difference with normal rape except that the other is committed by an unknown attacker.”

They caricature it.

They rationalise it.

They define and redefine its ‘qualifiers’.

They bury it in the empty rhetoric of bureaucracy.

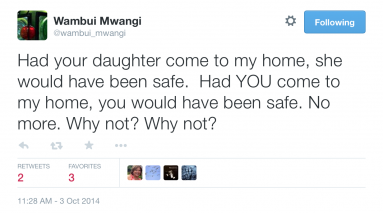

Given that even male Kenyan politicians publicly endorse domestic violence, Women in Kenya struggle to create and protect tiny sanctuaries, spaces in which we can survive, while we fight.

What should happen, then, when even these spaces are uninhabitable?

-Shailja Patel

Shailja Patel was not raped or beaten. Yet, still, she was allegedly violated. Most women’s first, second, third, or fourth encounters with sexual violence are considered trivial.

We are tired of being disbelieved and disappeared.

We will have our homes back.

We will have our bodies back.

We will have them back.