"Early bird" or "night owl"--most modern individuals consider themselves one or the other. People who lived before the Industrial Age were both.

Enviable is the sleeper who sleeps, who sinks into nothingness and remains there for a good seven to ten hours, rising again only with the sun.

Enviable and perhaps contemptible. "I hate a man who goes to sleep at once," complains Mark Twain.

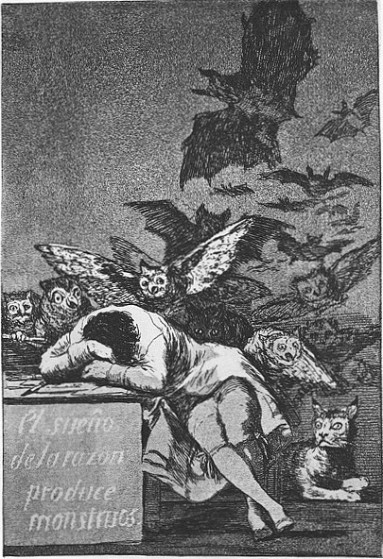

Exhaustion visits sound sleeper and insomniac alike. Yet whereas the sleeper eventually finds rest, the insomniac finds none. She suffers her exhaustion through the night, whose deep stillness only throws in starker relief the restlessness of her mind.

G.I. Gurdjieff understood the importance of placid thoughts. Whenever his disciples became nervous or agitated, he would hand them spades and command them to dig until their bodies wore out and their minds softened like warmed wax. Gaining wisdom depended on a hard day's work. If the disciple got a good night's sleep in the bargain, he believed, then all the better.

The sleeper who falls fast asleep counts herself lucky, then; she not only refreshes herself, but also obviates the need for the sort of spiritual spadework prescribed by the Russian mystic.

I wonder if sometimes I wouldn't benefit from Gurdjieff's remedy. I suppose I represent an intermediate case, a sound sleeper who experiences bouts of wakefulness. I drift quickly into that twilight state that precedes deep slumber. And I fall into that slumber until two a.m. or so, at which time I start awake, my alarm clock ticking a beat for the thoughts that march through my now-roused brain. Student loan debt, SARS, the entropic principle, laboratory meat, wormholes, feral cats, that strange moon of Neptune's on which volcanoes gush ice and the sky rains methane, New Zealand apples, eight-lane freeways, apartment fires, memory chips, social network data-mining--these and other preoccupations arrive unbidden in the small hours.

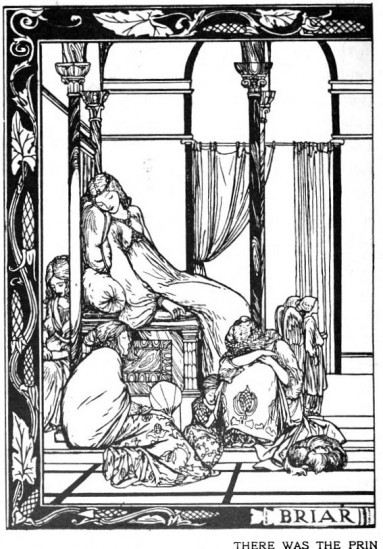

Terrible and lonely are those hours during which I fret and worry and stare at the ceiling. I certainly don't look forward to them. But there was a time when late-night wakefulness wasn't something to be dreaded but welcomed. Centuries ago, sleepers woke with pleasure, even eagerness. Between "first" and "second" sleep, so called, men, women and children stirred to enjoy activities domestic and romantic, spiritual and intellectual.

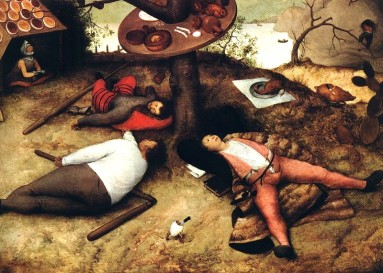

The idea of first and second sleep derives from a form of life that disappeared with the onset of industrialism. "Until the close of the early modern era," writes Roger Ekirch in At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (2005), "Western Europeans on most evenings experienced two major intervals of sleep bridged by up to an hour or more of quiet wakefulness." When an individual took her first sleep depended, like it does today, on disposition and life circumstances. Most, however, went to bed with the sun. Chaucer's "Squire's Tale" mentions that Canacee slept "soon after evening fell" and awoke again during the early hours of the morning. The thirteenth-century Catalan philosopher Ramón Lull characterizes first sleep as stretching from mid-evening to early morning, while the French writer Noel Taillepied maintains that it is "about midnight" when a person wakes from it.

The hours that followed first sleep individuals passed in diverse manners; no custom or obligation imposed itself on this time between times. Ekirch writes that this period bore no name other than the "watch" or "watching." Reluctant to leave a warm bed, many were content to do just that--watch. Others chatted with bedfellows, smoked pipes, comforted ill kinsmen or tended fires. Neighbors visited. Sometimes they broke bread. And frequently was the call of nature heeded. "When you do wake of your fyrst slepe," counsels the medieval physician Andrew Boorde, "make water if you feel your bladder charged."

Those souls charged with keeping house used the hours between first and second sleep to finish chores. These chores invariably fell to women, who tended children and livestock, and even brewed beer, as their husbands loafed in bed. Just how demanding the midnight hours could be for women of the laboring classes is amply illustrated in William Langland's Piers Plowman (ca. 1360–87):

They themselves also suffer much hunger,

And woe in wintertime, and waking up nights

To rise on the bedside, to rock the cradle,

Also the card and comb wool, to patch and to wash,

To rub flax and reel yarn and peel rushes.

The interval between sleep was for the agrarian housewife as unremittingly difficult as were daylight hours. Her days consisted of mind-numbing toil relieved only by bouts of black, dreamless slumber.

Regardless of how the hours between first and second sleep were passed, they were undeniably full. Individuals stirred into activity for good or ill. While the dutiful scrubbed and brewed, and while the lazy simply reposed, less scrupulous types burgled and pilfered under night's cover; and there were always those who in idle moments hatched evil plans. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, folks began to fall out of step with communal sleep rhythms, especially in the cities.

Franz Kafka, a noted insomniac, considers his affliction in a different light half a century later. In his short sketch, "At Night," he describes the loneliness of a vigil:

Deeply lost in the night. Just as one sometimes lowers one's head to reflect, thus to be utterly lost in the night. All around people are asleep. Its just play acting, an innocent self-deception, that they sleep in houses, in safe beds, under a safe roof, stretched out or curled up on mattresses, in sheets, under blankets; in reality they have flocked together as they had once upon a time and again later in a deserted region, a camp in the open, a countless number of men, an army, a people, under a cold sky on cold earth, collapsed where once they had stood, forehead pressed on the arm, face to the ground, breathing quietly. And you are watching, are one of the watchmen, you find the next one by brandishing a burning stick from the brushwood pile beside you. Why are you watching? Someone must watch, it is said. Someone must be there.

Wrapped in their bedclothes, the sleepers in Kafka's sketch bear only the outward vestments of solid, middle-class comfort. Members of a vast and wandering army, a people vulnerable to invasion; save for the watchmen, no one looks after them. Only he sees the historical continuum that undergirds their slumber. They are, as they have always been, unsettled and defenseless.

And unsettled and defenseless we continue to be, particularly as every aspect of contemporary existence conspires to rob us of our peace. "Disruptive," a fashionable term these days, flacks, shills and pundits apply to any new gizmo or "killer app" which promises to upend age-old ways of passing time. In a milieu of constant disruption, where can one find peace or rest? Enviable is the sleeper who sleeps, indeed; for she shows herself able to resist the constant barrage of enticements that the wired world hurls at her. She gets her rest while others keep watch over tweets and emails in imbecile expectation of goodness only knows what.