In the few days since I published last week’s post about the role of compliments in female friendships, I’ve become painfully aware of how often I give compliments. It’s certainly not something I want to stop doing, but when I found myself fussing over the color of a waitress’s nail polish in the presence of a friend who had just finished telling me what she thought of the piece—rather, when I suddenly felt like my friend had caught me in some weird act of benevolent manipulation—I started to think more about what compliments actually are.

Luckily, I’m hardly the first to that table: There’s plenty of research out there from linguists, sociologists, psychologists, and anthropologists about the fine art of the compliment. Robert Herbert, an American sociolinguist, published a fascinating study about the different ways men and women treat compliments that illuminated some of my experiences around complimenting women around me. Some of the findings:

- Women give wordier compliments than men: “What a great coat!” vs. “Great coat!”)

- Women employ more personal terms than men: “I like those earrings” and “You look great in those earrings” versus “Great earrings”

- Men generally don’t use the “I like/I love” construction when complimenting people of either sex; women use it frequently, most of all with other women

- American women are more likely to use “I like/I love” in compliments than British and New Zealand English speakers, and speakers of other languages (it’s rarely found in Asian languages).

I’m intrigued by this, particularly when examining the dual function of using personal terms in compliments. The first thought here is that women are simply speaking in ways we’ve been encouraged to socialize—we’re personal, not political, remember?—and would gravitate toward imbuing compliments with a personal touch that ostensibly aids sincerity and sociability, marking compliments as a more acceptable way of saying Gee, I think you’re swell. But looking at it from another angle, making a compliment personal is also a way of hedging a compliment. “I like that lipstick,” on its face, is about what the speaker likes, not about the lipstick; “Great lipstick” is about the lipstick, plain and simple. It simultaneously takes a risk (“Here is what I like”) and pushes it away (“Remember, this isn’t about you”); it’s assertive, not aggressive. It’s indirect, in other words—a communication mode linguists frequently claim women excel at.

But it’s in studying the reception of compliments that the connection between compliments and intimacy becomes clearest. Compliments given from man to man were accepted 40% of the time; only 22% of compliments given from one woman to another were accepted.

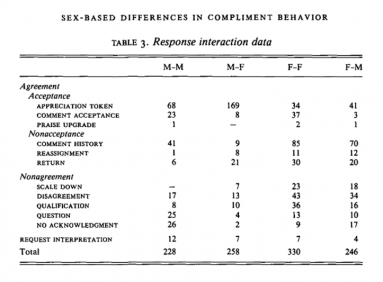

To be clear: Not accepting a compliment doesn’t necessarily mean rejecting it. By “accepting” a compliment in this context, we're talking “Thank you,” or an agreement with the compliment (whether that be a simple “I like it too” or an inflation of it, as in “Yeah, this sweater brings out my eyes, doesn’t it?”). The other forms of compliment response—nonacceptance, nonagreement, or a request for the compliment to be interpreted—can range from returning the compliment (“No, you’re so pretty!”) to scaling it down (“Yeah, well, you should’ve seen how my hair looked yesterday”) to reassigning it (“My hairstylist is a genius”). You can see the numbers here:

Language in Society, 1990, pp. 201-224, for 24 hours!

With that in mind, it’s easy to see why women might “accept” compliments about half as often as men—we’re taught to be deferential and modest and bashful and all that, right? But looking at this data, it’s clear that women know full well how to accept a compliment: When it was a man, not a woman, giving a compliment, women accepted it 68% of the time. The factor most likely to influence how people respond to a compliment isn’t what sex they are, but what sex the person giving it is. I’ll look more closely at male-female compliments later in the week; for now, what interests me isn’t why we’re likelier to say thank you to a man, but why we say anything but to a woman.

Scanning down the column listing responses to compliments given woman-to-woman, we find part of the answer. One number jumps out: 85 women out of 330 responded to a compliment with a “comment history,” defined in the paper as when the “addressee accepts the complimentary force and offers a relevant comment on the appreciated topic.” That is: A quarter of the time, we respond to a compliment with girl talk.

Janet Holmes, a leading scholar in linguistics and gender who conducted another influential (and gated, grrr) study on the gendering of compliments, puts it this way: Women recognize that compliments “increase or consolidate the solidarity between speaker and addressee.” Men recognize this too; “comment history” was also the number-one response men had when complimented by a woman. Part of this is women being assigned the emotional tasks within conversation: the how-did-that-make-you-feel-type stuff that, as the supposedly nurturing sex, comes “naturally” to us—and that gives men permission to articulate emotions that they might otherwise lack. But it’s not just limited to men: Women of different social statuses were likelier than men of different social statuses to exchange compliments. The solidarity isn’t in class, or if it is, it’s our classification as women that lies beneath what might masquerade as nattering on about perfume.

That solidarity is what makes compliments effective. It’s also what makes them poignant, and, as my friend Sarah put it, at times subversive. But given that appearance-based compliments are the most popular type of compliment shared between women—this is the research talking, not me—we’re tethering that effectiveness, poignancy, and subversion to how we look. I cherish the solidarity that compliments of all sorts can bring—nail polish, shoes, and hairstyles absolutely included. I just want us to remember that what makes us pretty is not what makes us women.