Wandering peoples knew no distinction between home-cooked dinners and meals "on the go"

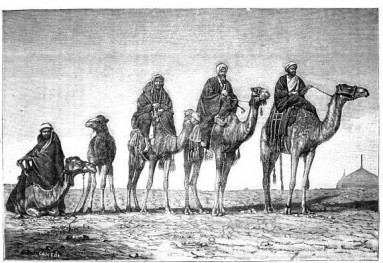

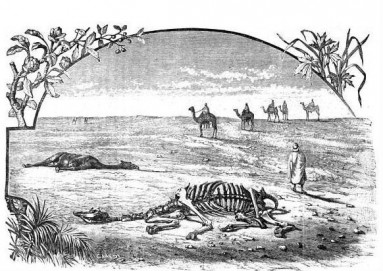

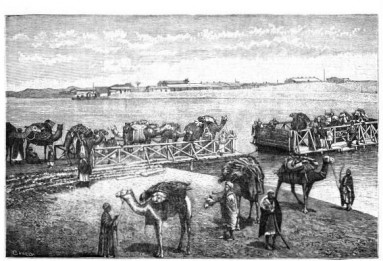

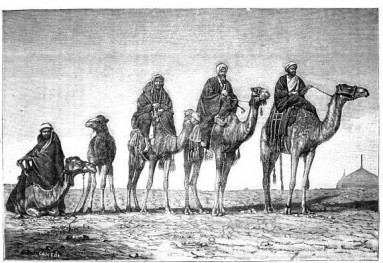

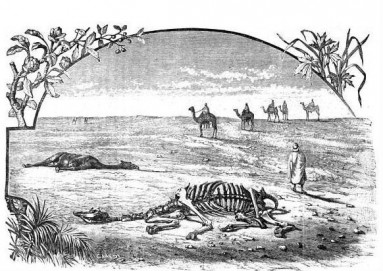

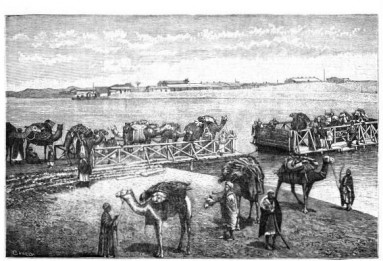

Illustrations from M. Jullien's Sinaï et Syrie: souvenirs bibliques et chrétiens (1893)

I’m moving again. This move will be my fourth in eight years and, like the three before it, owes not to any restless impulse but to banal necessity. Contrary economic winds have blown me from Arizona to New England, from New England back to Arizona, and from Arizona to western Pennsylvania. Now I’m returning to New England. Relocation ranks just below divorce and illness in terms of unusually stressful events. I feel this fact palpably.

Relieving my stress a bit is the fact that I’m headed for a boskier part of New England than the place of my previous stint. Adding to my stress is the fact that I soon must do the one thing dreaded by every itinerant book lover: paring down her library to a portable size.

"I am much inclined to live from my rucksack, and let my trousers fray as they like." --Herman Hesse

It’s a sad task, deciding which books get dropped in moving boxes and which get dropped drop down the donation chute. In truth I haven’t the heart for it. I’ll end up keeping most of them, even though it will mean lugging some sixty cartons of them through high summer’s swelter.

I tried in the past to break myself of this packrat-ish impulse, lest it end up breaking my back.

"Do not free a camel of the burden of his hump; you may be freeing him from being a camel." --G.K. Chesterton

I used an e-reader for a time. It crashed, and some 300 books vanished into the ether. (The event served to remind me that technological innovation is a notion quite distinct from technological progress.) Its screen dark, its keys mashed, it presently lies crushed beneath four volumes of the Durants’

The Story of Civilization. (These, incidentally, are coming with.)

"Whereas the migrant leaves behind a milieu that has become amorphous or hostile, the nomad is one who does not depart, does not want to depart, who clings to the smooth space left by the receding forest, where the steppe or the desert advances, and who invents nomadism as a response to this challenge." --Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (1987)

Yes, a rootless life is a ruthless life if it is encumbered by books or other possessions. Keeping their poems and stories safe in their brains as they drove their flocks to pasturage and water, nomads of yore traveled only with what they needed. Through grassland, over high plateaus, and along riverbanks they moved by day. By night they rested in tents or under the stars.

The Persians called the spare black tents in which the nomads of Afghanistan lived “leather butterflies.”

Morning would see them afoot again, marching alongside a raucous parade of sheep, goats, and dogs, with camels and donkeys following behind heaped with storage boxes containing the few domestic goods deemed important enough to bring along.

"Some people treat themselves worse than they would their dogs, just for the sake of money. They spend four-fifths of their lives in this way without seeming to see or feel the sunshine of life, and, then, if they are successful in a material sense, they use the fruits of this self-imposed and unnecessary serfdom in the attempt to make the rest of their lives happy by indulging in extravagant luxury, and fail, because their natures have become so sour, or their tastes so perverted or dead, through lack of proper nourishment or cultivation, that there is nothing left for the comfort and ease, which they fondly imagined their money could buy at this time to work upon." --Charles Summers, The Nomads: A Socioeconomic Novel (1903)

The few domestic goods usually consisted of bedding and kitchen utensils. The latter exemplified elegant efficiency, a virtue esteemed by all nomadic tribes. To make their meals Turkic nomads required only a large hemispherical vessel called a

qazan, a shield-shaped grill, and a type of skewer called a

shish. A large wooden bowl sufficed to serve the cooked dish, and tableware consisted mostly of knives and a double-bowled wooden spoon that looked much like the number eight. Kitchens more elaborately outfitted might boast thin rolling pins, colanders for skimming curds, and stones for grinding grain.

Mongols made due with even less than did their Turkic counterparts. Many families had only a flat-bottomed cooking pot of sheet metal in which to simmer their flour dumplings. To cook meat they sometimes used an animal’s rumen sack filled with water and hot stones. Such simple cookware meant plain meals, to be sure. Yet nomadic life demanded that food be fuss-free. Portability and resistance to spoiling were virtues cherished above all others. Dried grain fit the bill, as did cured meat and sausage. Almost all nomadic tribes had a recipe for the latter. Afghan nomads’ sausage often consisted solely of meat and freshly milled grain; Kazakh nomads made their sausage of horse meat and smoked it over a mix of elm, juniper, spruce, and meadowsweet. When they had mutton, they stuffed it in the sheep’s own innards and roasted it over coals. And when sausage-making proved impossible, they covered hunks of brined meat with oil, garlic, and cheesecloth and dried them over a fire.

To modern readers nomad cuisine no doubt brings to mind the old Fats Waller song, “All That Meat and No Potatoes.” And it was true that wandering peoples weren’t ones to eat their vegetables. Most avoided any kind of farming. Wild herbs, onions, and garlic sometimes found their way in the mutton comfits and dishes of lamb wrapped in plucked skin. Yet such additions were not relished as much as you might imagine. When the young Genghis Khan and his family were robbed of their flock and sent into the wild to shift for themselves, they subsisted on forage of the steppes -- berries, wild apricots, Russian olives, edible roots and greens. To the great conqueror these seemingly tasty foods were anything but. A true Mongol, he believed, ate lots of horse meat and little besides. “Agriculture has been and remains a ‘catastrophe’ at all levels,” writes John Zerzan

"We can either passively continue on the road to utter domestication and destruction or turn in the direction of joyful upheaval, passionate and feral embrace of wildness and life that aims at dancing on the ruins of clocks, computers and that failure of imagination and will called work." --John Zerzan, The Nihilist's Dictionary (1994)

, a leading “green” anarchist thinker. It appears nomads felt much the same way.

If nomads forwent veggies, it didn’t seem to matter much. The raw milk they drank appeared to ward off most deficiencies. From camel, sheep, yak, and goat they consumed it in all of its forms: fresh, soured, churned into butter, and dried and salted as curds. British traveler and poet Charles Montagu Doughty recalled once encountering two young Bedouin men who had traveled several days from their camp. With them on their journey they had brought a milch camel and a single bowl.

Much of what we know about 19th-century Bedouin life comes from Doughty. He traveled widely from 1876 to 1878 in the vast desert regions of Hejaz and Nejd, spending time in oasis towns. He collected his observations in his 1888 book, Travels in Arabia Deserta, which T.E. Lawrence had reprinted in the 1920s.

Such provisioning served to sustain nomadic travelers -- but only just. On several occasions, Doughty encountered men who complained of “creeping hunger” and begged biscuits of him, despite having as much milk as they could drink.

Doughty recorded how the Bedouin felt about the relative merits of their three main dairy sources: "Camel milk is the best of all sustenance, and the very best is that of the bukkra, the young camel with her first calf, as lightly purgative. Ewe's milk is very sweet and fattest of all, it is unwholesome to drink whole, it kills people with colic ... ewe buttermilk should be let sour some while in the semily (butterskin) with other milk, until all are tempered together, and then it is fit to drink. Goat milk is sweet, it fattens more than strengthens the body."

Though much of his time in the Arabian desert Doughty spent with the Bedouin, he never found himself having to subsist on camel’s milk. Bedouin rules of hospitality stipulated that the best food be lavished on guests. Often this would come as generous portions of boiled mutton served up in a paste of milk and wheat or roasted camel calf meat adorned with rice, the recipient perhaps never suspecting that such a feast was usually reserved for holidays, and that his host had likely emptied his stores and devastated his flock to provide it.

Everyday fare was more austere yet. For the Bedouin it typically came in the form of a single meal of bread and milk taken after the evening milking.

"A loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou." --Omar Khayyam

This is not to suggest, however, that these wanderers were ascetics. Even an environment as rugged as theirs rendered up delicacies. Expert foragers and hunters, they ate a truffle-like desert plant called

kemmaye and various small game -- Cape hare, Ethiopian hedgehogs, porcupines, and rodents. These last creatures they threw on the fire, fur and all. From their livestock’s milk they made a clarified butter called

samn, which they churned in an inflated animal skin and seasoned with coriander and cumin. They loved the stuff so much that they drizzled it on whatever foods they could and even drank it straight, snuffing some up their noses for good measure.

"O thou, who departest from me, mounted upon the clear-coloured camel, bearing upon its back the foursided saddle, / And its bag and neck-leather, and well-ground flour, with the coffee-beans, and the sweet-smelling Tombac." --Bedouin poem

What the immediate environs failed to provide could be had by trade. Along with jujubes, tea, and salt, mulberries were a favorite, as were caravan dates. The latter could be found at all oases. Easy and economical to transport, cheap, and nutritious, they were said to taste like dry cotton wool and ashes, albeit not unpleasantly so. Supreme among all delicacies, however, was coffee. “Where there is not coffee, there is not merry company,” went an old Bedouin saying. At the coffee tent men gathered to exchange news and tell stories. Doughty recounts an occasion when no less an eminence than “a ruler of seven tribes” carried out the coffee ceremony, roasting, pounding, boiling, and serving “the cheerful mixture with his own hand.”

"These characteristics of the land, reacting on the inhabitants, render them in great part of unsettled predatory habit, intensely individualistic, jealous of the secrets of water and pasture which barely make life possible, and proud of an exclusive liberty, which has never been long infringed." --David George Hogarth, The Penetration of Arabia (1966)

A century ago nomadic Bedouin made up some 10% of the total Arab population. Today they account for 1%.

It was these simple, noble pleasures shared among free men that led Doughty and other Victorians to romanticize nomadic life. "The poorest Bedouin, in his ragged goatskin tent, and coarse woollen mantle, owns no superior on earth, and looks with contempt on the pomp of a Turkish pacha," wrote traveler John Lewis Burckhardt. These nomads he saw as models of "kindness, benevolence, and charity," for they were "a nation of brothers."

A century later, fascination with this nation of brothers hadn't waned. "Homeless, cut off from the world," writes Albert Camus in his 1957 story “The Adulterous Woman,”

they were a handful wandering over the vast territory ... which however was but a paltry part of an even greater expanse whose dizzying course stopped only thousands of miles farther south, where the first river finally waters the forest. Since the beginning of time, on the dry earth of this limitless land scraped to the bone, a few men had been ceaselessly trudging, possessing nothing but serving no one, poverty-stricken but free lords of a strange kingdom.

Recipe for "Stuffed Eggs for Traveling" from Santa Rosa Recipes (1891): "Boil eggs hard, remove shell, cut through center and remove yolks; chop yolks very fine, adding a very little onion, mix with a little oil, vinegar, cayenne pepper, salt and black pepper, place into the whites; put the eggs together as though whole, wrap in tissue paper twisted at the ends."

Nomads elsewhere didn't fare well either. The Soviets settled Kyrgyz nomads in agricultural villages. Prolonged drought, meanwhile, destroyed the ability of Afghan nomads to continue their way of life.

By the time Camus’s adulterous woman was fantasizing about joining in ceaseless trudging, nomads had arrived at something of a standstill. The combustion engine came to replace camel and donkey as the nomads’ beast of burden, destroying their wealth as it did so. Politics joined technology in the havoc. Government policies in Egypt and Israel, along with oil production in Libya and the Persian Gulf, forced many Bedouin into sedentary life and wage labor. Even in Doughty’s time, oases were devolving from cheerful kaffeeklatsches to fiefdoms where men sparred over politics and taxes.

Whatever its difficulties, the natural simplicity of the life nomadic maintains a certain allure. Unfortunately, more than a few of us these days are getting a taste of a more modern and decidedly unromantic version of it, one which leaves us possessing nothing, yet serving someone.