Photograph from The Postal Record (1892)

"At 8 o'clock last evening at Smith's Coffee and Cake Saloon, Mr. Samuel John Buggins of this city -- the well known sausage maker, was united in marriage to Miss Judy Dumps, the daughter of the ex-keeper, Dumps, of the apple stand at the Hoboken Ferry," an 1856 edition of Young America cheekily reports. "After the ceremony a splendid entertainment was given in the principal saloon, including a 'soiree densante,' 'cafe au lait’ and 'gateauz du beurre,' in Smith's best style. This may be considered as the beginning of the fashionable season."

In nineteenth-century New York, nothing went better with radical politics than coffee cake. Manhattan's Lower East Side boasted some three hundred "coffee and cake saloons," where anarchists and socialists tucked into crullers as they debated everything from the theories of Marx and Bakunin to the literary merits of Tolstoy and Ibsen, and the success of the latest performance at the Metropolitan Opera House. Late into the night they talked and between outbursts of indignation or sympathy sipped strong cups of tea à la russe adorned with thin slices of lemon.

Most saloons hosted regular customers, but almost anyone would find himself welcome. Quiet, frowning "chess cranks"; gaunt, earnest critics; doleful actors; sloe-eyed cocottes -- all crowded round the saloons' tables from ten o'clock at night until one in the morning. But they did not crowd indiscriminately; each had their favorite haunt. The city's letter carriers, for instance, favored Dolan's Coffee and Cake Saloon, which operated under the management of the cheerful, mustachioed John Meehan.

Meehan considered himself a friend of the postal workers, an affection he cultivated in childhood. At thirteen his uncle had hired him to help around the saloon, and he did so with enthusiasm. While about his tasks he often overheard the postal workers muttering into their coffee cups. Their interminable shifts vexed them, and they saw no relief short of quitting altogether. "No limit to a day's work," they complained.

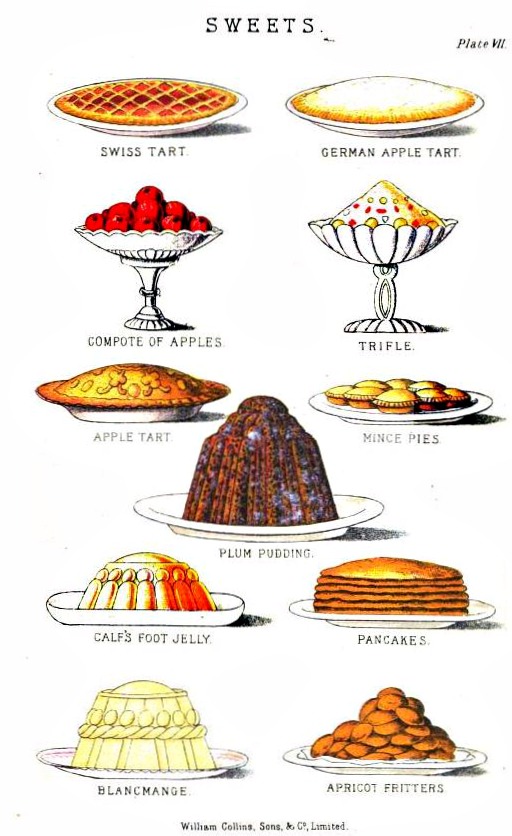

Illustration from Handbook of Domestic Cookery (1882)

"Richard Marshall, better known as 'Butter-cake Dick,' kept a coffee-and-cake saloon under the then Tribune building," writes George Washington Walling in Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (1887). "I could look from my post across the Park and see the genial light of this haven of refuge, the windows deliciously frosted with congealed coffee-steam. O, how I wanted coffee!"

The letter carriers' plight moved young Meehan, who resolved one day to help them. So vital to the saloon's success did he prove that after a few years his uncle promoted him to manager. Meehan soon garnered a fifty-percent stake in the business (an interest which belied the fact that almost one hundred percent of the responsibility fell to him alone). Finding himself comfortably situated, Meehan deemed it high time he made good his vow. Suggesting that the postmen organize, he offered his advice, his financial backing, and his establishment for their union headquarters. Thus the New York Letter Carrier's Association leapt into existence. "Well, boys, you have started, and now don't let this thing fail," Meehan proclaimed to those whose cause he championed. "While I have a tongue or a dollar I will help you get what you want."

Recipe for New York Butter Cakes from Paul Richard's Baker's Bread (1918): "Take one quart of milk; one pound of flour; eight ounces of butter, and eight ounces of sugar. Put the milk, sugar and butter in a vessel on the fire and let it come to a boil; when it is boiling add the sifted flour, stirring it in well with an egg beater; take it off the fire and put in a wooden bowl; let cool till you can hold your hand in it, then mix into it by degrees five whole eggs and five yolks. Add to this mixture two and one-half pounds of white bread sponge, or milk sponge, and sufficient flour to make it like a tea biscuit dough. Let this dough rest, and prove on for half an hour; roll into a sheet and cut into large biscuits; eggwash and lay in granulated sugar; set on pans single; let it prove, and bake to a nice color."

Meehan did indeed keep his promise. When reporters stopped by the saloon for a bite, he buttonholed them and, plying them with strudel and steaming java, extracted promises of articles and notices favorable to the letter carriers' cause. One such convert, William Dougherty of

The Evening Telegram, published many pieces in support of the eight-hour work day. Soon hundreds of influential New Yorkers rallied to support the letter carriers. They circulated petitions, which thousands signed. Placards and posters they pasted all over the city. Before the letter carriers knew it, they had triumphed, winning equitable working conditions.

The postal workers continued for years to frequent Dolan's Coffee and Cake Saloon. Indeed, all New York saw it as a haven for working stiffs -- and rightly so. An enlightened employer, Meehan heaped on his employees benefits for which other laborers would agitate for decades to come. To work at Dolan's meant a job for life; only death or illness altered the payroll. Those too old or sick to work received pensions at their full salaries. Such largess did nothing to dampen the eatery's profits. The smashing success of the first location made necessary opening a second, which likewise flourished, and put paid to the notion that you cannot have your cake and eat it, too.