(By Gina Patnaik and Aaron Bady, both graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley)

Last November, a few days after videos of riot police beating Berkeley student protestors were blowing up on youtube, an article in the New York Times announced that UC-Berkeley's Chancellor Robert Birgeneau had been travelling to establish a satellite campus within the intimate confines of Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park. Because Birgeneau had been in Asia during the entirety of the week leading up to and following the events of that day, he had had very little to say about what was happening on his campus, with the exception of two extremely tin-eared and downright offensive emails. We knew he was out of town while campus police were brutalizing their campus, but that's all we knew.

(photo via OccupyCal)

In retrospect, though, the chancellor’s junket is the perfect coincidence: he couldn’t have had anything to do with police violence against anti-privatization protesters because he was quite literally too busy advancing plans to privatize the university. But of course, police brutality and privatization are structurally interwoven: as anti-privatization protesters are fond of saying, behind every fee hike, a line of riot cops. “Privatization” describes the inexorable move away from any sort of education whose value can’t be immediately monetized, and so police violence reminds us that visions of public education which conflict with that of the administration will just as inexorably be suppressed by armed force, as surely as customers trying to break into a store after business hours.

As a closer look at the events around the November 9th strike reveal, moreover, the connection between the force meted out on student bodies on campus and long-developed plans to chart new directions for the university -- in China and as an online university -- are not simply conceptually related. The Chancellor’s physical absence from campus on Nov. 9th and the way his place was quite literally taken by the physical violence of the police speaks to the very concret retreat from actual university space, what they call the “bricks and mortar” campus, that gives “privatization” a tangible form.

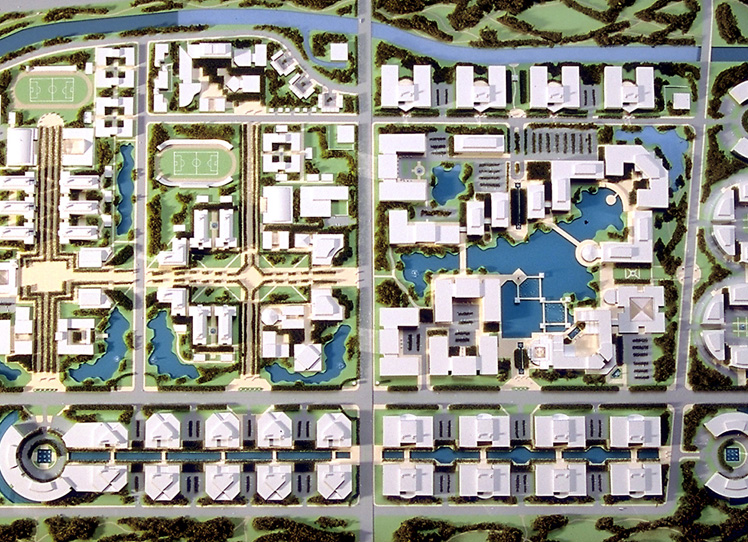

To understand what privatization is, let us look to the Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park, whose website describes its intention to “progressively replace the life cycle of traditional industries” as a way to “represent the revolutionary transformation trend of China’s economic development pattern.” In one sense, this is simply business-speak for the kind of state-run economic development such parks represent, replacing “traditional” industrial development. Yet this is also a rather stunningly literal statement: re-vamping the “life-cycle” of technological innovation also means absorbing as much of the entirety of the human life cycle into the contoured confines of the 25 square km Hi-Tech Park as possible; everything from government research, multi-national corporations, residential units for workers, eating spaces, a few well-regulated parks, and now, even education, are to be laid out into the neat grid of Zhangjiang’s campus.

(photo via)

There is good reason to be at least a little skeptical about this projection; UC-Berkeley has a long history of coming up with its own funds – funds raised from skyrocketing student tuition – after promised donations fail to actually materialize. Yet as UC-Berkeley breaks new ground in refiguring the university as an ancillary project of multinational corporations, perhaps rather than asking whether it will pay, we should question why new revenue streams are the only desirable outcomes the university seems capable of chasing.

In any case, while Birgeneau has said that the satellite campus will only house joint research projects, Berkeley Law School Dean Christopher Edley, Jr. clearly envisioned a much broader range of possibilities while talking to the Daily Californian:

“We are exploring degree and non-degree teaching, executive education, and online teaching, as well as more traditional exchanges and research collaborations.”

Edley’s language sounds familiar to us, because he’s also been spearheading similarly “exploratory” plans to develop an online UC curriculum, one which will charge students UC tuition -- currently close to $22,000 -- to enroll in online classes, even though, as Wendy Brown has observed, comparable online programs typically anticipate a drop-out rate of up to 70%. But of course, that figure has nothing to do with the programs’ overall profitability: since students still pay for courses and programs they don’t complete, cyber campuses profits even when they don’t educate students. And despite vigorous opposition from the faculty senate, a pilot version of the online UC is currently in progress.The project is also going forward despite, it should be noted, the fact that Dean Edley utterly failed to raise the money he promised to raise to fund it: to make up the difference between the $7.5 million needed and the $750,000 raised, the university ended up springing for $6.9 million of the start-up costs. In the early stages of the project, Edley said he “should be shot” if he was unable to obtain millions in private funds for the project, a line many of us are recalling, now, with a certain zesty interest.

As a result, the brick-and-mortar campus languishes while Chancellor Birgeneau and Dean Edley chart a new agenda for the university by turning to for-profit online education and corporate tech parks as models for the future “space” of UC-Berkeley. And this is a transformative course: both the online UC and UC-Zhangjiang Tech Park jettison the arts, humanities and social sciences almost from before the very beginning. In the case of the online university, this streamlining comes as a result of a curriculum that only offers courses lending themselves to online format, typically ones that rely upon rote memorization. Biotech research initiatives that may turn into degree-granting programs focus on securing agreements with multinational corporations and Chinese national labs, but defer consideration of the programs’ educational mission until after research plans are well under way. As a result, both programs fit education to available technology and available funding (or funding that is promised to be available).

It should not surprise us, therefore, that plans to corporatize and technologize the university have been coupled with an accompanying disinvestment from and disinterest in the current space of the university. As a result, the coincidence of police brutality on the Berkeley campus and the chancellor’s trip abroad points to more than a series of logistical missteps on the part of an administration physically distanced from the university campus. It stems from a deep, structural lack of concern for the future of the current UC-Berkeley, both the campus itself and the students it serves.

It should not, therefore, surprise us too much that while police are paid to beat students in the name of "health and safety," the university can't even pay people to pick up trash on campus anymore:

(photo via the East Bay Expess)

As the article that photo is taken from explains, budget cuts to staff have meant that groundskeepers who were originally "hired as experienced gardeners, are now forced to spend most of their time picking up trash while the campus grounds fall further into hazardous disrepair"; far from "America's Greenest Campus," UCB won't even spend money to recycle. But this is not austerity; when the university can come up with an unexpected $7 million for an online education that no one but Dean Edley seems to want, we are talking about priorities.

In the immediate aftermath of the police violence last November, it seemed like Chancellor Birgeneau was so busy re-imagining the space of the university that he simply ceded campus control to the police (albeit through a chain of administrative command so murky as to defy any kind of accountability). Certainly this is true, and certainly it is, in and of itself, fairly damning: in his now infamous email to the “campus community,” Birgeneau claimed ignorance of what had happened, that his trip to Shanghai gave him only “intermittent” updates on the situation unfolding on the Berkeley campus (sparking quite a lot of ironic commentary on internet malfunctions during a technology summit).

Thanks to a public records request by the ACLU, however, we now know that Birgeneau was being disingenuous:

Vice-Chancellor Breslauer wrote to the chancellor at 4:28 p.m. on Nov. 9, after the first skirmish, stating “Protesters locked arms to prevent police from getting to the tents. Police used batons to gain access to the tents. There are still 200-300 people gathered, watching, and, in some cases, screaming at the police...”

Within the hour, Chancellor Birgeneau wrote back: “This is really unfortunate. However, our policies are absolutely clear. Obviously this group want[ed] exactly such a confrontation.” Chancellor Birgeneau then wrote back again, at 5:36 p.m. Pacific time, approximately an hour after receiving the initial email, stating: “It is critical that we do not back down on our no encampment policy. Otherwise, we will end up in Quan land.”

Refuting the Chancellor’s face-saving excuses is not really the point; the ACLU’s efforts only confirm that the Chancellor’s long-standing policy of pre-approving and pre-praising any and all police actions is still in effect. But his emails do demonstrate quite clearly that a lack of information about what was happening was not the Chancellor’s problem; the problem was that he lacked interest. When the Vice-Chancellor informed him that “Police used batons to gain access to the tents,” he did not express concern for the manner in which these batons were “used,” nor did he request more information about what lies behind that word, “used.” He already knew everything he needed to know. “Obviously,” he pecks out on his blackberry, the people in tents got what they wanted, what they deserved, what was coming to them.

Having been very physically present that day and that night, I must confess that the word “obviously” sticks deep in my craw. On being told that campus police were beating student protesters with “batons,” the Chancellor regarded the motivations of the students as so transparent, and the police reaction so beyond question, that he does not request more information. The situation is, to him, “obvious.” And so he writes a blank check, one that would result in further police violence later that evening. This is, in my opinion, a profound and damning ethical failure on his part, and we should never forget that.

Others reacted differently. As Bob Hass, the former US poet laureate, recalled in the NY Times:

Earlier that day, a colleague had written to say that the campus police had moved in to take down the Occupy tents and that students had been “beaten viciously.” I didn’t believe it. In broad daylight? And without provocation? So when we heard that the police had returned, my wife, Brenda Hillman, and I hurried to the campus. I wanted to see what was going to happen and how the police behaved, and how the students behaved. If there was trouble, we wanted to be there to do what we could to protect the students.

What we didn’t know then, we now know: “the police had returned” because they got the order to do so from the administration: the Chancellor had re-iterated to his Vice-Chancellor that it was “critical that we do not back down on our no encampment policy.” And so, having been directed to continue beating students (until morale improved?), the police came back, and continued beating the students and faculty members.

Here, we have another apposite coincidence: when university chancellor Robert Birgeneau heard that his students had been beaten, he asked for no details and ordered the beatings to continue; when poet and teacher Robert Hass heard that his students had been beaten, he went to see for himself, and then he put his body where it could do some good.

But I’m not interested in trying to judge Chancellor Birgeneau; his own words damn him more effectively than I need to. Instead, I’m interested in understanding why he was so removed, so distant, and so uninterested in doing anything but upholding a policy against tents (and at this point, it’s worth adding to the record the fact, which later came out, that the policy against tents was not originally meant to apply to students; the faculty members who formulated the policy were thinking only of non-student campers, as one of them recalled at a later faculty senate meeting).

The phrase “Quan land” provides part of the answer to the Chancellor’s certainty: in his mind, the worst case scenario was what Oakland Mayor Jean Quan had allowed to happen in the first few weeks of Occupy Oakland, where a group of occupiers gained a foothold precisely because the city had not used police violence, immediately, to enforce their policy. Now, of course, Jean Quan is better remembered for the police violence she eventually authorized against Occupy Oakland, but for Birgeneau, apparently, the lesson of Mayor Quan was that more police force, sooner, was the way to handle things.

But I think the most important element is, simply, this: the relationship between fundraising and higher education has become a zero-sum game in which attention to one is predicated upon unapologetic neglect of the other. I am not suggesting that fundraising is an unconditional evil, of course; I’m grateful for the faculty and administrators who devote endless hours to grant writing and donor solicitation in an attempt to keep the university’s doors open. But I second Celeste Langan’s concern about an administration which directs its energy “toward seeking donations from entities that ought to be taxed,” especially when deep structural transformations in the university itself seem to precede even the existence of the revenue itself. To put it bluntly, our top administrators are not only allowing massive deals like the Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park – or the online education initiative – to determine the course of the university’s educational mission, but seem incapable or unwilling to imagine any other way forward.

For a truly disorienting sense of how removed the chancellor was from his own campus, compare these images of Sather Gate, which stands on the northern tip of Sproul Plaza:

(photo via UCBerkeleyNewsMedia, Occupy Cal)

To this imitation of the gate at the 2010 and 2011 “Berkeley Ball” in Shanghai (sponsored by VeriSilicon Holdings Co., Ltd), a gala event that followed the Berkeley Biotech Forum where Birgeneau and company were last November:

(photos via Berkeley Club of Shanghai)

Sather Gate is an important piece of campus architecture. It once marked the entrance to the UC-Berkeley campus, and although the grounds were expanded to include Sproul Plaza in the 1960s, the archway still serves as a symbolic gateway to the heart of campus. Once upon a time, it was a campus tradition to block the gate, once a year, as a symbolic demonstration of the campus's autonomy from the community outside.

Let us note, then, that in the former image, protesting students are flooding through Sather Gate to fill Sproul Plaza with signs, bodies, and tents. One student holds a sign spelling out recent tuition and fee increases (around $5000 in 2005, just over $22,000 in 2011). But in the latter photo, Sather Gate has morphed into a pseudo-proscenium, a background for photo-ops with potential investors, representing no more than the symbolic capital which Berkeley has become: less a place than a certificate. This “arch” opens onto nothing: it frames a projection screen, allowing external images to bounce back endlessly.

I wish that I had more information to share or post about UC-Berkeley-Zhangjiang Tech Park. In fact, I wish that any public source had information to share about such plans. But the administration’s silence has been as telling as it is characteristic: side-stepping any public discussion around corporate partnerships, the administration chose instead to release a single two-paragraph announcement, the contents of which have been copied pretty much wholesale in all media outlets covering the story.

Turning to the images and language used to imagine the university might seem like a way to side-step more pressing questions such as: the university president’s refusal to relinquish emergency powers, never-ending fee hikes, and the devaluation of the arts and humanities, which just a few of the consequences of privatization. Dwelling on just a few of the proliferating photos and messages swirling around recent events, however, might just allow us to attend to the deep structure of the administration’s disregard for its academic community and the campus space which that community works each day to create.

When asked, for example, about what students might miss out on when they “go to class” at the computer screen in their bedrooms instead of on an actual campus, Dean Edley opined, “What you won’t get? There won’t be beer bashes, yeah.” That’s right: college campuses are only good for keggers. If you shared my initial response to this statement - an inclination to forgive what must have been a misguided and altogether regrettable slip of the tongue - Edley has reiterated and defended his views on multiple occasions. And Dean Edley’s disregard for the current university is matched only by that of UC President Mark Yudoff who confided to the New York Times that “being president of the University of California is like being manager of a cemetery.”

These are not just examples of administrative rhetoric at its most hyperbolic, or of “down-to-earth” men speaking off the cuff. This is who they are. The language we use to describe our world reflects our understanding of its contours, and of how we want to shape that world’s future. And so, to sum up: in Dean Edley’s words, the university campus is value-less ground; in President Yudoff’s, it’s a dead wasteland. These are precisely the sorts of imaginative de-populations of the university that underwrite Chancellor Birgeneau’s ability to describe UC-Berkeley students as “intruders” and then send in riot police to forcibly remove them. In the interests of “hygiene and safety,” administrative regulations aggressively and violently champion the banal, and in so doing, they actively foster the exact campus atmosphere which allows them to dismiss university culture as value-less - and so move towards privatizing it. The space of the university campus is not only good for nothing; the space must be rigorously protected so that it becomes good for nothing.

In the weeks after November 9th, the administration’s attempts to devalue the university and its campus campus reached even greater heights. Their responses to weeks of protest took shape not as discussion but as a recitation of campus policies and release of PR articles. My personal favorite was when, in a maddening display of solipsism, the Berkeley Graduate Division published a series which re-cast the recent protests and ensuing police brutality as an “extraordinary season” of activism on campus. Written entirely in the past tense, the articles “offer resources for understanding” a movement which was, in the view of the administration, a thing of the past. Photographic montages generate a visual corollary for this narrative, juxtaposing exuberant students holding signs with Robert Reich speaking to thousands on the Mario Savio Steps. Images of riot police beating of students and faculty, dragging professors by their hair, or arresting 40 people have, of course, been tastefully excised. In the final image, which occupies the bottom right corner of the screen, a man power-hoses the (now-empty) Mario Savio Steps. The occupation is over; health and safety has been restored. The students have been removed.

(photo via UCBerkeley News Center)