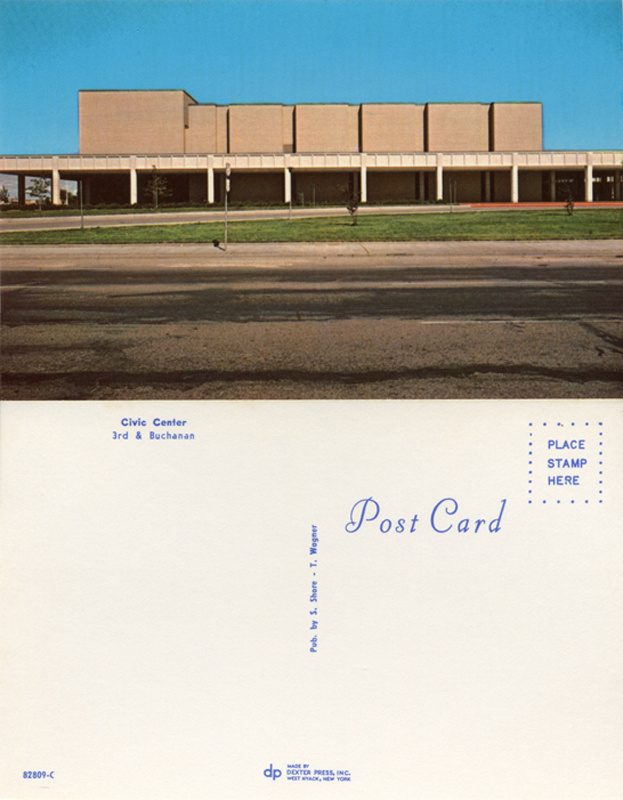

I have a book called Boring Postcards. It contains reproductions of postcards much like the one above. They tend to depict empty interstates, motel parking lots, quotidian commercial storefronts (auto parts stores, smalltown banks), diners, storage facilities. Many evoke an idea of primordial American emptiness, seizing on the still permanency of the printed postcard image to make a meta-statement about eternity. The postcards conjure a world where ordinary use of taken-for-granted infrastructure imposes no wear, inspires no conflict, occasions no longing. Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens.

Of course, by labeling these images "boring" they become interesting: They stand for a quintessential boredom and are never truly dull. They conjure a nostalgia for the never wanted, for an experience beyond desire. In Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind, Patricia Meyer Spacks describes boredom as a modern condition, a socially constructed sense that our ability to experience our own impulses is or should be blunted: "Almost always it suggests disruptions of desire, the inability to desire or have desire fulfilled."

It can be a relief to have a respite from desire, given how much energy is put into stoking it. So much time and money is invested in "managing consumer demand," producing ads, generating hype. In a consumer society, it's a rare delight to experience things without having to want to possess them.

Spacks cites Sean Desmond Healy, who likens boredom to anorexia: Boredom is the pathological refusal to find nourishment for the mind, an inability to bring oneself to try to be engaged. But she also notes the links between boredom and leisure, between emerging notions of freedom and passivity. There is a sense in which the printing press invents boredom, and then cameras reinvent it — every new medium posits a new form of seductive boredom as it finds its particular ways to think for us, to entertain us. Each has its particular mode of passivity that redefines boredom's domain and invigorates its glamour — the superiority of indifference; the luxury of idleness; the comfortable, conscious refusal to concentrate.

Drawing on the term's early modern origins, Spacks views boredom as primarily productive, a spur to innovation, but that view seems conditioned by the idea that distractions are inherently scarce. They aren't, particularly not with phones and social media. They makes no interval of time too short to become bored. When you have a phone, every moment of potential impatience, no matter how brief — waiting in line, waiting for the light to change, waiting for others to stop talking — is an opportunity to check in for some algorithmically tailored, constantly refreshing content available at the drag-down of a screen. The incentives for becoming distracted have never seemed higher. Distraction itself is becoming boring.

Boredom has become rhythmical for me; every three seconds I seem to become bored, regardless of what I'm doing or what I should be focusing on. Distraction is no longer a relief from tedium but its metronome.

Wouldn't it be better to be bored than constantly distracted? Boredom could be some kind of Zen space of non-attachment: My boredom is actually a sign of my focus; my refusal to be distractible is so militant that I will decline to pay attention to anything.

When I was young, I associated boredom with forcible deprivation and assumed that if I had more autonomy, I could seek out the good things in life that were being denied me. I wonder if I would have construed the Internet's plenitude as boring too, simply because it would have been accessible to me. It feels like boredom is more likely to be linked now with the "paradox of choice," and the need to "escape from freedom," as if we all enjoy meaningful choices and broad freedoms.

Freud famously remarked that the goal of psychoanalysis is to "transform neurotic misery into ordinary unhappiness." I sometimes feel like I need a therapy that can turn overheated distractibility into ordinary boredom. In the same way that I am attracted to the "boring" aesthetic of Boring Postcards, I'm often tempted to romanticize boredom itself, make a dignified accomplishment out of the refusal to become engaged. Adam Phillips, in "On Being Bored," writes that "in ordinary states of boredom the child returns to the possibility of his own desire." Since boredom signifies a will to independence, Phillips suggests that the "capacity to be bored can be a developmental achievement for the child." Through our boredom we can know ourselves as potentially willful, impulsive.

If boredom feels like an accomplishment, it helps explain "boring" entertainment like slow TV, or otherwise aimless reality shows, programming that does little other than remain undemanding — or rather just demanding enough that we feel a friction in our attention, so that it feels like hanging out with people. Phillips writes, "Boredom, I think, protects the individual, makes tolerable for him the impossible experience of waiting for something without knowing what it could be." The "impossible experience of waiting" is more palpable than ever, and culture is struggling to invent new forms of boredom to compensate and counteract it.

Maybe we are tiring of things that are constantly trying to compel our interest. Soon we'll practice boredom as a form of resistance to the hegemonic attention economy.

***

The Stephen Shore retrospective that recently opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York made me think of Boring Postcards. That's not just because one of Shore's own books of boring postcards (Civic Architecture) is on display, hanging by a cord from the ceiling; also on display are the postcards Shore had made, a series called Tall in Texas, featuring more or less generic locales in Amarillo. Apparently he tried to sell these commercially and reportedly used to surreptitiously stock postcard racks with them while on his road trips across the U.S. The point wasn't to parody the postcard aesthetic but to assimilate into it.

At the MoMa retrospective there is also a partial re-creation of All the Meat You Can Eat, a 1971 show he curated that juxtaposed Polaroids and newspaper clippings with pornography, crime-scene photos, glossy stills of airliners, and nondescript postcards of institutional buildings and blasé street corners to explore the range of what he calls "vernacular photography." I take that to mean photography that occurs outside the aesthetic anxiety of proving itself as legitimate "real art." Just as boring postcards become interesting when they are curated and taxonomized, so do vernacular images become artistic. The frame makes the art, not the subject matter or its execution.

Spacks opens her boredom book with the claim that "writing resists boredom, constituting itself by that resistance. In this sense all writing — at least since 1800 or so — is 'about' boredom." You could say the same thing about all art; it all commemorates a decision to do something rather than nothing. Art that looks deliberately boring foregrounds and interrogates that commemoration.

Boringness is obviously not an inherent quality but a description of a relation, of one thing's relative level of fascination with respect to some other, more exciting thing that remains unimagined, amorphous. Many of Shore's photographs, for me, point toward this unseen thing. The wall text at MoMa suggested that Shore's subject matter, as well as his method of pointing and clicking and moving on, with little staging, reshooting, or postproduction, reflected his search for a "neutral" perspective. Large sections of the show look like a collection of Jandek album covers. Many of Shore's images seem to aspire to appear accidental and deliberate at the same time, as if hoping to capture impulsiveness itself, not as a characteristic of the photographer's but as something ambient in the nature of things, that makes them intermittently photographable. In Shore's epic collection of snapshots American Surfaces, the impulse for taking a photo emerges as oracular. It can be trusted to be, in itself, the subject of any image, emergent regardless of what is recorded. Again, as with Phillips's view of being bored as an achievement, boringness serves to index impulsiveness, marking the conditions of its possibility. Only a boring image can convey the excitement of picture-taking.

Like postcards, these snapshots are relatively small, and they require you to crowd close to the wall to view them. I kept having to lift my glasses up to see details, the same way I have to when I am trying to do the crossword. The small scale of these images conveys a kind of intimacy that often counteracts the spaciousness they capture. The postcards too convey a similar tension, the intimacy of potential one-to-one communication paired with intentionally generic images that attempt to eschew personalization or idiosyncrasy. And it appears again in a commissioned series of photos Shore took of bungalows. Isolated families in standalone houses, but taken together they become homogeneous, archetypal. What is stifling, suffocatingly intimate from one perspective becomes sedate and anonymous from another.

Boredom and intimacy are probably inseparable, such that one can always be counted on to signify the other. This may be why it feels like the endlessly distracted life militates against intimacy, eradicating the moments and spaces in which it can flourish. Intimacy requires a willingness to resist impatience, to dwell in it.

Shore mainly posts to Instagram now, and it is easy to make a case for this as an extension of his interest in vernacular photography and unstudied, spontaneous production. But viewing his work there situates it right where it shouldn't be, in those impatient moments when I'm flicking through images, waiting to resume another distraction.

(This post taken from my newsletter.)