After several days of enduring a solid, nagging throat ache, I took a one-day vow of bed rest. Though I found myself going in an out of lucidity, with shivering, body aches, and all the other concomittant symptoms of acute coryza (a.k.a. the common cold) I availed myself of no drug harsher than a 200-milligram ibuprofen every few hours. And I found that I couldn't speak: every careful attempt at forming a sentence ended in vacuum-filled gasp and a look from interlocutors that mixed pity, concern, and amusement. Why the illness had lodged itself so resolutely in my pharynx was not immediately clear; the medical doctor I consulted after not being able to swallow anything but liquids for those two days took a strep throat test (negative) and handed me a 'Cold/Viral Illness' FAQ that a friend pointed out was printed out from the internet, that entity which requires no co-pay or in-network restrictions. The 'unusual' symptoms listed under 'Reasons to See Your Health Care Provider' included 'Confusion,' 'Sensitivity to light,' 'Shortness of breath or wheezing,' and 'Any other symptoms that seem unusual' (I can't say exactly what I find so poetic about including confusion and skin rash in the same preventative guide, but I do). Instructed to drink hot fluids and avoid contact with others, I retreated to the agoraphobic sanctuary of my bed.

In sickness I encounter a no-place, an imaginary nation where my body is the only inhabitant. No-place has two primary, contradictory affects which I feel in turns. Beatific: the rapture of ill health suspends time and blurs the clear outlines of everyday objects, and for one entire day I slide in and out of the fourth realm of sleep (the dreamless one you usually bypass without the aid of drugs). Fussy: ineffectual grumpiness, a sincere desire to have my head petted (a sensation I find odious, even offensive, otherwise), and in a prolonged state of physical discomfort. Trapped in the graspable nowhere I read every 'leisure' reading I'd been putting off, from Lies: A Journal of Materialist Feminism to Fred Moten's poetry to some Pasolini essays from Heretical Empiricism to AnOther Magazine (which has become an unbearable mercenary for fashion advertising since the last issue I opened some ten years ago). I did it with the joyous realization that ill health and promiscuous reading go together.

Somewhere in the mottled delirium of wakefulness and a gifted bowl of soup I learned that it was Louis Althusser's birthday. While I haven't read him much in recent years his writings formed a large part of the beginnings of my college years, so much so that as a freshman I came to perceive the film department as a midwife to critical theory. Althusser's works on ideology (reconceptualized as 'our imaginary relationship to real conditions of existence') were not just influential on their own; as professor to Jacques Rancière, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and at least a half-dozen other philosophers in the French tradition (almost all of whom would break with him in some fundamental way, as Rancière did) the sum total of his mentorship rivaled just about any other communist or Marxist contemporary in effect.

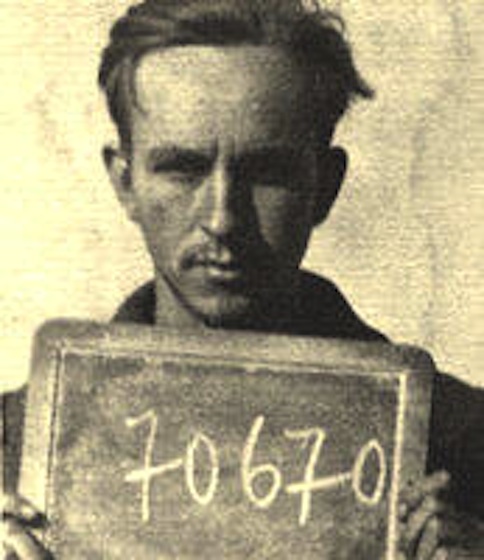

His mugshot, pictured above, was circulating along with the birthday pronouncements yesterday, and since then I've been amazed to find almost no mention of when and where it was taken, and whether it had anything to do with the 1980 strangulation of his wife, the revolutionary Hélène Rytman, eight years his senior.

Following his birth to a pied-noir family in French-colonized Birmedreïs, Algeria, Althusser lived primarily in two abodes: at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris (first as a sickly student lodged in a single suite at the infirmary and then as a tutor and professor at a faculty apartment) and at the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital. He endured mental illness and psychological instability his entire life, at least three decades of which were characterized by manic depression—the most startling speculation about his mental capacity is that he was able to produce anything at all. And he did produce, even writing the memoir L'Avenir dure longtemps (published in English as The Future Lasts Forever) from the mental ward. The book details his killing of Rytman on a low-lit November dawn in their shared apartment where he was found crying, 'J’ai étranglé Hélène!'

The 'definitive' biography of Althusser's life, or the text that is most closely read alongside his own, is Yann Moulier Boutang's Louis Althusser, published twenty years ago; if it appears that care at a mental facility was favored over prison because of Althusser's fame, Boutang's narrative refutes that. He 'calculates that [Althusser] had to be taken into a hospital on an average of once every three years and that he was "immobilised" by depression for perhaps half his working time' (John Sturrock, 'The Paris Strangler').

From Alice Kaplan's review of the memoir:

As a result of the murder of his wife, Louis Althusser was declared unfit to stand trial by reason of insanity—in French, this is called a non-lieu. This verdict preceded and preempted a trial. The non-lieu saved Althusser from the nightmare of a trial, and possible condemnation, but its consequences were enormous. As a person deemed unfit to plead, he lost his right to a trial—that is the right to testify and be held responsible for his actions; he lost his right to enter into contract (his affairs would be handled by a legal guardian) and hence by extension—at least symbolically—his signature, his authorship.

Althusser, calling himself a 'missing person,' claims to be writing his memoir from this 'non-place.' He writes not as some latter-day Chateaubriand, from beyond the grave: He writes buried alive.

Althusser would write an entire memoir about his life without the concrete memory of the act of choking Hélène, save for his 'coming to consciousness [...] with his thumbs massaging the hollows in his wife's neck.' There are several interpretations of the violence of the act and Althusser's mental state during it. Paddy Lyons counters Sturrock's claim that the autobiography was a self-victimization, offering that the niamid treatment Althusser received was 'disastrously' doubled, reducing him to 'waking dreams in which he was subject to suicidal compulsions,' with Hélène becoming suicidal in the meanwhile. The final act of throat strangulation aside, it doesn't appear that Hélène could have hoped for a return on her devotion (since she nursed him even at the cost of her own sense of despair and decline in health): when she was voted to be purged from the French Communist Party, Althusser did not abstain or recuse himself, instead sheepishly joining the majority banishing her in 'a moment of cowardice.'

None of this aids in deducing the source of Althusser's mug shot, since he was never jailed for killing his wife, but I am still keen on finding out where. [Update: From Viewpoint Magazine's Asad Haider: 'That photo is from [Althusser]'s five-year stay in a prison camp during WW2. He was prisoner #70670 in camp Stalag XA.']

In truth, in my foggy and feverish mental transportations I started wondering about the existence of my own mug shot. There is at least one. It is housed at the University of California Berkeley Police Department. My recollection of the photo is one offensive middle finger raised at the bookings officer. I made at least one visit to the Records Unit of the UCBPD in the aftermath of the photo because I needed a police clearance to obtain a Brazilian visa. They refused to give me one, so I got one from the City of Oakland instead, which could vouch for the Brazilian government that I was not, in their official capacity to determine such a thing, a known criminal.