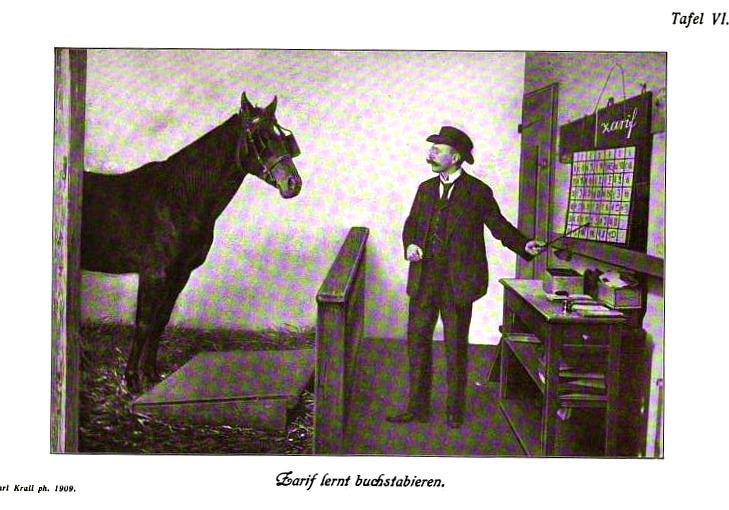

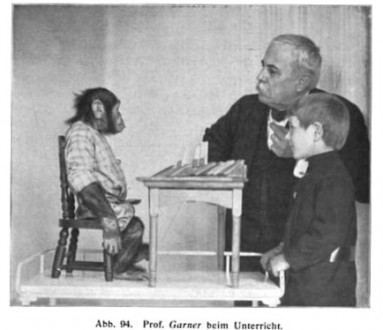

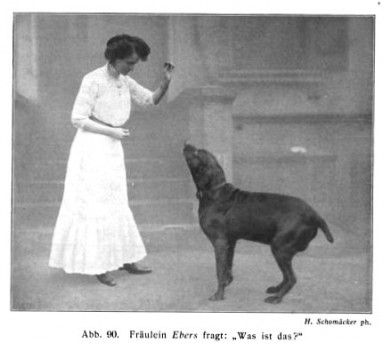

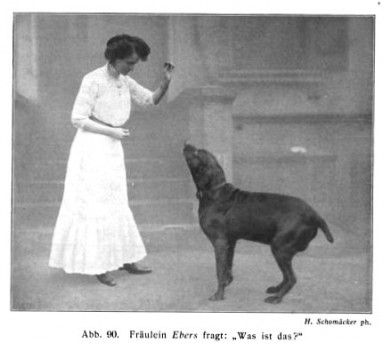

Photographs taken from Karl Krall's Denkende Tiere (1912)

All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely critters--at least as far as Mrs. Midnight's Animal Comedians were concerned. The rage during the 1753 London season, this troupe plied its trade in a small, elaborately decorated theater named the Castle Tavern. The show starred poet Christopher Smart, who appeared in drag as Mrs. Midnight and orchestrated the splendid entertainments his trained dogs and monkeys performed in period dress and powdered periwigs.

Mrs. Midnight's also featured entertainers higher up the evolutionary ladder; child prodigies and street musicians often graced the stage.

The playbill advertised battle reenactments and dances, the great "Ballet Dance" being the troupe's greatest coup. A masterpiece of staging, it presented the siege of a miniature fortified town. Monkey defenders "manned" its ramparts, clutching halberds with steely resolve. The attack swiftly followed. An army of dogs stole upon padded feet, prancing forward, dancing backward, climbing ladders, vaulting walls, all the while gripping swords in eager muzzles. Simian wit met canine bravery but proved no match; the victors soon hoisted their standard aloft as the vanquished doffed their tiny caps. Soon thereafter the familiar notes of "God Save the King" sounded in the theater, accompanied by barks and yowls, hoots and howls.

Charles Dickens believed that children who were forbidden to dance and play became "like monkeys with something depressing on their minds."

Relief from clash of arms came in the form of various

entr'actes. One featured three monkeys in the roles of Harlequin, Pero, and Columbine (the last attired in an unwieldy hoop dress). In another, monkeys wearing cloaks and cocked hats rode dogs that jumped over bundles of sticks. Later there took place a domestic scene: Two more monkeys, bedecked in ribbons and pearls, dined on cake and wine as another stood in attendance, plate held primly under his arm.

The dancing-dog craze lasted barely a century. In The Menageries: Quadrupeds, described and drawn from living subjects (1826), author James Rennie writes that "[t]he dancing dogs of the showman ... are almost extinct; though, now and then, his pipe and tabor are heard in some obscure street of London."

Mrs. Midnight's extravaganza sparked a vogue for animal domestics.

The Adventurer, a periodical of the day, reports that "every boarding-house romp and wanton school-boy is employed in perverting the end of canine creation." In homes throughout London, pugs poured tea and pomeranians proffered scones. Many was the householder who cherished hopes that his tractable and clever mutt would make his fortune.

From a 1909 issue of Good Housekeeping: "A man who has been very successful raising thoroughbred dogs, especially of the large breeds, gives this recipe for a most nourishing and economical DOG FOOD. Procure a soup bone and boil as for soup. When all the juice has been extracted, take the bone from the broth, remove the meat, chop fine and return to the soup. Stir in sufficient cornmeal to make a thick mush and set aside to cool. When cold, cut in slices and feed to the dog as required."

What reward did the Animal Comedians receive for their crowd-pleasing exploits? Did their keeper regale them with backstage feasts of hazelnuts and apples, bones and offal? Did they retire, footsore and exhausted, to gilded cages and feather beds? No such luck. Novel delights often conceal common outrages. The "method of teaching" employed by the impresario Smart to instruct his players in a "modern way of footing" involved, as one intrepid reporter discovered, "placing red-hot iron plates alternatively under each hind leg, and in quicker or slower succession as the variations of the tune required." For the hapless stars of Mrs. Midnight's revue, the Castle Tavern was a theater of cruelty, and show business meant a dog's life, indeed.