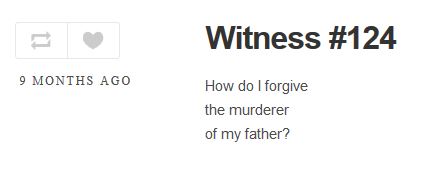

If this was a question—a simple prose sentence—it would open outward: in the answer to the question, we would find its wholeness, completion. It would open up a problem, which would, in being answered, be resolved. Question follows answer, answer completes question, turning an unsettling question mark into a settled period. But it tells a complete story even by its incompletion, since it propels its unsettling remainder outward, onto the resolution that doesn't come. In other words, since it does not resolve—and is not answered—its lack of answer still completes the story: the lack of closure is the answer, the impossible status of not being able to forgive the murderer of my father, a rhetorical question because it is unanswerable, because there is no answer. That lack of answer is the punctuation mark, the absent period that converts a question into a statement. An answer to the question, expressed as a desire to know how, becomes the completion of that desire, its fulfillment. The question is a problem, an itch that is solved by being scratched and made to disappear.

Calling it a poem, however, condemns us to remain with the text, preventing it from becoming a simple question which could then have a simple answer. The text moves under our hands, comes alive: an aspiration to forgive the murderer—to find in that event a solution to the problem—can become a self-critique, even a condemnation: How is it that I do this? It can become a outraged demand that this has happened, apparently without the knowledge of the speaker: How do *I* of all people can forgive the murderer of my own father? It might even defamiliarize the word “forgive”: forgive, forgive, forgive, for, give, for-give, How Do I For Give… the more times you repeat it, the more strange it becomes. How is it that I do this thing forgive? What even is forgive?

Calling it a poem, in other words, produces simultaneity and multiplicity where there was, before, a longing for singularity. Constative utterances aspire to a condition of truth, such that a question demands the statement that truthfully answers. But in its non-constative function, a performative utterance—and what is a "poem" but words, performed?—refuses to allow that to happen. Calling this question a "poem" renders it something more than simply unanswered; it renders it unanswerable. There is no space in which is could be answered, precisely because it is complete (the poem ends) in its completion. It does not want an answer. It does not want a truth.