[These are notes toward a history of the legal and aesthetic concept of salvage. Since I've written on salvage a couple years ago (specifically on the image of a salvagepunkish world that became a staple of genre film, television, and so on), I've returned to the concept on different ground, with a specific interest in the legal framework carried within it and greater suspicion of the real limits of its mobilization again and again. So these notes toward a different tack. They also form a touchpoint for a series of new essays on empire and image I'll be posting here in coming days and weeks.]

“but are we not all wreckers contriving that some treasure may be washed up on our beach, that we may secure it [...]?"

- Henry David Thoreau, Cape Cod

A beginning: beating the meteorological odds. Fernand Braudel writes, in his famous study of the Mediterranean in the Age of Phillip, of the “Mediterranean victory over bad weather” – i.e. the advent of year-round shipping.

Braudel’s use of the term "salvage" in line with how we tend to use it now (i.e. gathering what's still sellable/recuperable from a disaster) is almost anachronistic, because salvage at that time predominantly designated not those soggy sellable remnants but a payment or appropriate portion of goods given to those who stopped the ship from sinking in the first place. (And in English common law, for instance, this “appropriate portion” was often weighed heavily against the sailors who might come to the rescue, covering only their labor and time – and hence giving little incentive beyond vague appeal to human decency.)

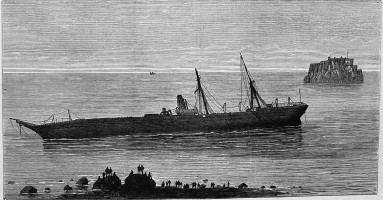

However, the situation Braudel describes – underwriters impelled and profited from increased chances of calamity and waste, and they handled this salvage work through the creation of private firms and/or collaboration with independent contractors – remained salient in the centuries to come, long after state and municipal services became more common. And does so today, in the era of Blackwater/Academi: just weeks ago, the imbroglio called the Costa Concordia has just been passed off to a Florida-based salvage company, TITAN, a subsidiary of Crowley Maritime, who will drag the eyesore to Genoa, to be scrapped and melted down to make forks or struts that will pointedly not bear the name of their source.

Much as the history of sabotage is inextricably bound up with the new explosive concentration of carbon power in trains (and the consequent new capacity to distribute failure across a vast infrastructural network), salvage’s first steps toward becoming a general principle of how we conceive a world of permanent crisis was impelled by changes in motive force. One in particular: the steamship, which made it newly possible to rescue “distressed” vessels and to haul up the truly scuttled from the deep. (As a result, the salvage jurisdiction of the English Court of Admiralty grew hugely in importance.) Both the scope and temporal range of salvage expanded tremendously, revealing that this labor of letting nothing remain dead to the world was that both spurred surging industrial capital and wholly depended upon it.

In the same years, the Romantics tried to lay claim on nature as a source of sublimity, with some measure of success. As for the resurrection and consequent sale of what has been seemingly reclaimed by nature, reduced to landscape, and booted from the circuit of value, industry’s technique will be the uncontested arbiter. And so begins two subsequent centuries of squabble over the meaning of the wasted.

That dominance of machinic force and seriously capital-intensive coordination did not come quickly, in part because of libidinal entanglements. For an oceanic imagination not eager to relinquish the image of rapacious pirates (after the decline of real existing piracy in the late eighteenth century), maritime salvage fit the bill flawlessly, thanks especially to the figure of the “wrecker.” Because while the majority of a wrecker’s real work oscillated between the two operative meanings of salvage (saving ships from going all the way down, or recovering the waterlogged and putatively lost), the notion that stalked newspapers, plays, and novels of the nineteenth century dreamt a more cunning and vicious labor: using guide lights to intentionally coax ships not to safety but to shoal and reef. It’s this meaning that underwrites Guy Debord’s line in his final film: “Wreckers write their names only in water,” meaning, in short, propaganda by the self-negating deed.

Once stuck or wrecked, plunder became an act of easy scavenging: sit back and let the tide wash in the loot. It finds a later echo in one of the lesser-celebrated of salvage films, Peter Weir’s debut The Cars that Ate Paris (1974), where a town runs off the wreckage of motoring tourists they impel into crashing.

As Jamin Wells points out, though, even as this largely incorrect image of wreckers continued to fuel lurid tales, like Charles E. Averill’s 1848 novel The Wreckers: or, The Ship Plunderers of Barnegat, it was slowly replaced over the course of the nineteenth century.

First, it was supplanted by the figure of the brave, trustworthy, innovative, hearty, and pointedly white male individual wreckers, such as Captain Thomas Albertson Scott, who were less scourges of the high seas than tamers of the waves. Second, though, this image of a respectable individual battling the elements in the name of property and creating the image of what Wells calls a “subdued, ‘understood’ ocean” – an aqueous propriety, a territory identical to its map – was itself outpaced by the economic fact of just what such rescues required. As ships to be saved got bigger, so too the technology of saving itself, demanding not only a salvage tug but tremendous outlays of capital and resources that only corporations could handle. The spectacle of salvage adjusted accordingly, drifting from the amoral scavenger to the righteous engineer to the force of machinic technique itself.

Fittingly, with this came a transformation of spectator’s behavior, in addition to their expectation of what can possible be altered by non-“experts,” horribly presaging our contemporary equivalent form of dismissal (high finance as supposedly both too big to fail and too complicated to allow intervention into.)

For example, when the ocean liner St. Paul wrecked in 1896 on eastern Long Island, tens of thousands swarmed to the site, 20,000 from Philadelphia alone. Yet if reports can be believed, nothing was plundered by the crowds, who came not to salvage themselves but just to witness the feat of salvaging, of capital straining to drag itself back to the surface. In an upset repeated with increasing across decades to come, looking comes from behind to beat looting.

The Liverpool Salvage Corps

On drier land in the same years, increased urban concentration made fire an almost unprecedented threat to life and property, barring early exceptions like Constantinople’s Nika riots and London’s recurrent Great Fires. As with marine salvage, insurance companies took up the slack, at least in the name of the specific properties they backed, and a number of “Salvage Corps” were formed, first in New York in 1839 (the New York Fire Patrol) and first in name as the Liverpool Salvage Corps in 1842. These private fire companies carried out three lines of duty: diminishing risk prior to a blaze; lessening risk during one (laying sheets of wet canvas over things deemed of value); and sifting through the ashes to assess loss. There are stories of the London Salvage Corps picking though the aftermath of a fire in a piano warehouse, like some CSI of property, counting charred keys to try and determine how many ex-pianos make up the musical charnel field.

Early cinema is well-marked by depictions of firefighting, like Porter’s 1902 Life of an American Fireman, favoring it as a kind of good clean heroism similar to that on offer in second-wave wreckers. However, the form of calculation at work behind the Salvage Corps stood wholly at cross-purposes to these archetypes of selfless saviors. After all, by the start of the twentieth century, marine salvage had enshrined in Lloyd’s Form of Salvage Agreement its dictum of “No cure – no pay”: salvage crews only got rewarded if they stopped the ship from going down, providing ample occasion and hurry for what might resemble altruistic heroism – at least until the time came to demand fair remuneration. With the fire salvage corps, though, such grand gestures were reserved only for those who had paid in advance. The rest could, and did, burn. It made the principle of managed risk assessment and discrimination of what and who is worth saving, that principle that came to mark so much of the urban and infrastructural history of the twentieth century, part of the fundamental territorial patchwork and class stratification of cities.

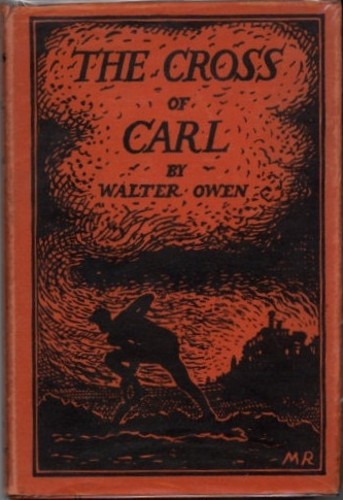

The nominal heroism of the salvager took a further, if not decisive, blow in the First World War when the term became inextricably linked to the meaning most common today (salvage of the already devastated). In that war, “salvage units” were employed, ranging from German repurposing of British tanks to the bleaker work of combing the fields of the dead and literally taking the shirts off their backs. Reporters spoke of a sudden dawning horror that their gas masks, necessary thanks to the nascent technology of chlorine gas deployed at Bolimov and Ypres, were made of fabric cut from the uniforms of the dead. In photos, recovered rifles are stacked like cordwood, arranged into pyres. It is this situation that led Walter Owen to write arguably the first and last pioneering salvage-splatterpunk hybrid, The Cross of Carl (1931). A novella whose censorship in Britain should have surprised no one, it tells the tale of Carl, a foot soldier shot seemingly dead in the trenches. He wakes in a giant corpse salvage factory, where he and the other fallen have been baled together with wire to be rendered into soap. Unsurprisingly, he goes spectacularly mad, becomes a prophetic anti-war wraith of sorts, and suffers the unusuallt brutal fate of being marked for death by the war machine. (The second time personally at the hands of a Marshall who declares him "a rag already" and stabs him before crushing Carl's neck beneath his boot in a grave.)

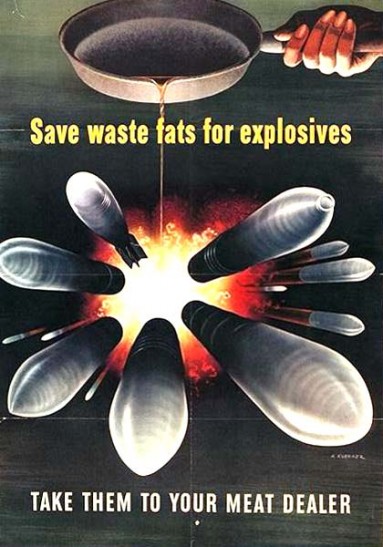

Speculative, sure, but barely, as this use of fat anticipates the American Fat Salvage Committee of WWII, who urged the gathering of domestic fats for use in explosives. As the accompanying Disney propaganda cartoon trumpets, “A skillet of bacon grease is a little munitions factory.” From the re-weaponization of corpses to the weaponization of the national home in the name of producing further corpses: a salvage principle in toto, letting nothing combustible go to waste.

It is also this situation of the war, taken broadly, that generates the crux of all salvage thinking to follow, especially the kind that became unmistakably visible in the last decade.

Small Sailor's Home, 1926

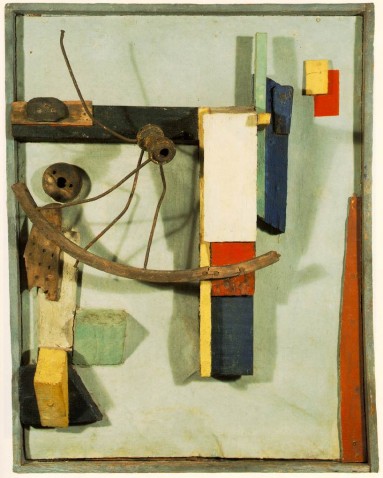

This quality takes shape especially in the cultural production in the immediate aftermath of WWI, most explicitly posed in Schwitters’ Merz: “Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz. It was like a revolution within me, not as it was, but as it should have been."

Salvage is perhaps best conceived as an operation within these drifts of meaning, rather than their driving force or a proposed solution to such visions of waste or redemption amongst the foreclosed. Even if conceived as a solution or tactic, it has no inherent “politics,” cannot be chalked up as somehow cogently radical or reactionary. It is at once a small image of how to function outside of the policed reproduction of capital, gender, and empire and the total form of thinking that undergirds and naturalizes paths of capital that end in Agbogbloshie.

Salvage, in short, comes to be the basic shape of thought underwriting our imagination of crisis, especially in these years of more visible downturn. It is a form already adapted to the gnawing sense that as specific as the coordinates of the crisis may be, it belongs to a wider field – not cycle, not progression, but situation – of collapse that hardly can be exited, redeemed, or borrowed out of.

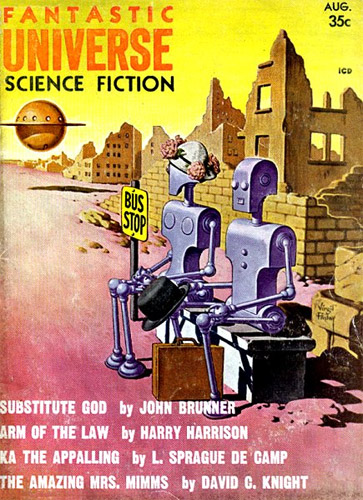

However, that passage through speculative culture of novels, films, comics, games, and television, salvage indeed appears predominantly as a content – a thing done, a kind of people who do it with flair – and as an economic mood, including the sense of ceaseless rehashing of pulp genre inheritances for a last whiff of profit. We can find it in the history of speculative fiction production itself, as in the 1950s, sci-fi magazines like Fantastic Universe, which primarily published stories rejected elsewhere, were known as “salvage magazines,” finding nuggets of worth – or just grabbing up cheap – from what the majors had passed on.

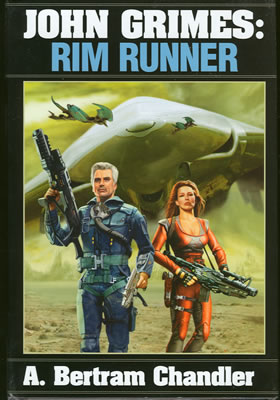

A. Betram Chandler was, at one point, the master of an aircraft carrier, required by law to remain on the empty hull before it was hauled to southeast Asia to be ship broken for scrap. It's little surprise that in his John Grimes stories, maritime salvage history goes cosmic with a “Gaussjammer” yet remains otherwise intact for various off-world naval adventures: "So if it's a ship, it's probably a derelict," murmured Grimes. "Salvage..." muttered Beadle, looking almost happy. "You've a low, commercial mind, Number One," Grimes told him.

The space opera inclination spans from mid-century on, from Robert Wells The Spacejacks (1955), and its “Ryder’s Recovery Systems United,” to Paul J. McAuley’s “The Passenger” (2002): “All of them hulks. Combat wreckage. Spoils of war waiting to be rendered into useful components, rare metals, and scrap."

In Melissa Scott’s Mighty Good Road (1990), extensive descriptions of how cosmic salvage contract work interfaces with large-scale financial interest produces an echo of the actual history of maritime salvage, even if the dangers tend toward the fantastic. It found its way into American homes briefly in Salvage 1, the 1979 TV show scientifically advised by Asimov and starring an all-salvaged spaceship named Vulture and a protagonist who dreams of salvaging the junk on the moon.

Elsewhere, salvage presents itself more as a needling concern and anxiety about what the continued accumulation of waste will do, especially when it exits its socially designated zones of exclusion. (The half-step toward the actually existing treatment of humans as such waste seethes under all of this.) In James White’s Deadly Litter (1964) – a proto-Gravity with a breathtakingly literal title – space litter does the titular promised, hurtling off the Sun’s orbit to become a lethal payload.

Charles Platt’s 1968 Garbage World provides a precursive image of financial turbulence and revenge of accumulated waste as good as any. Fittingly, it takes place on an asteroid, as salvage and asteroids are inextricably linked in the history of speculative fiction, as the latter are imagined as sub-planets without tight orbital coherence, just drifting around waiting to shatter (the ubiquitous asteroid field in which to lose pursuing ships) or ruin things for those with the decency to obey a tighter cyclical path (family structure in Armageddon).

In Platt’s novel, the asteroid, called Kopra with scatological tongue firmly in cheek, is a dumping site for the wealthier lumps of rock in the area. Now covered with ten vertical miles of trash, its residents eke out a scavenger life (of "the drinking, the dirt, the dancing and the debauchery") on its surface. But the waste has accumulated to the such a height that it has become a threat: not, of course, to the life of the Koprans but to the surrounding “pleasure planets,” which stand to be pelted with their own refuse not that the natural gravitation balance of Kopra has been disturbed. To solve it, they must displace the Koprans and destroy the ground on which they walk. In other words, out of concern for the better-off in other areas, they evict the poor from the site, because the excess of a system, it suggests, can only be displaced for so long before it must be properly destroyed.

Survival Research Labs, apparently being contemplated by a nude cyclist

If one strand of salvage was space opera, the more common one, especially in years surrounding the financial crisis, is a variant of the earthly post-apocalyptic. In some, like the Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic (1971), salvage becomes a basic human operation for processing the trash left behind here – Earth as cosmic rest stop – by far more advanced beings, turning subsequent human evolution into itself one long labor of retrofitting. Others keep it more strictly terrestrial, situating salvage – both collection and montage of the ruined – as the key procedure of survival in a hell we ourselves wrought, from Paul Auster’s In the Country of Last Things (1987) to Paolo Bacigalupi’s Ship Breaker (2010) to less whole-hog doomsday fare, like Cory Doctorow’s Makers (2009) or Slick Henry in William Gibson’s Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988), modeled after Mark Pauline of Survival Research Labs.

Doomsday and/or a shitty The Prodigy video

Arguably the most popular diffusion of this has been cinematic, acid-etched into permanent pop cultural memory by – what else – the Mad Max series, which served primarily to 1) bind salvage to a vision of use-value (and libidinal value) that outstrips exchange, 2) structure that as a condition of a neo-primitivism in the wake of market and carbon energy collapse, and 3) render this a transposable aesthetic, yet another -punk to enter the recombinatory grist mill. Films like Richard Stanley’s Hardware (1990) make this entirely clear, as the compelling inhuman work of a machine that scavenges anything, human material included, to keep itself running is posed against those for whom salvage is just an art practice, and a terribly sub-Burning Man assemblage at that. And crisis-era films like Wall-E (2008) and Doomsday (2008), which were of course produced before the crash, extended that even further: the former by making a landscape of the unsalvageable into the site for a tale of more-human-than-human robot love (and redemptive farming), the latter by making salvage just one more post-plague barbarian’s flourish amongst others, neither more nor less political than smearing neon paint on your machete. Again, it reduces down to something that merely looks, for all intents and purposes, like a rejected Prodigy video, indicating how slow the uptake has been on any new aesthetic thought surrounding salvage.

Years when one sits on sacks that carried the substance on drinks while sitting on the sacks

Outside of speculative fiction, the last years have seen the idea of salvage proliferate through the social world, on two fronts. First, the points where attempts at sustainable life and community run most viciously into financial operations, resulting in the “fire sale,” the new landscapes of foreclosure, the junk bond, the sub-prime, and mass default, all images of efforts to scrap value from what was previously excluded from consideration and of the violent consequences that follow. Second, he wide diffusion of a salvage aesthetic in the neo-yuppie cultural fixation on “architectural salvage.” That thirst for the reclaimed, which works to disavow actual historical particularity by fetishizing any minor grit that belies origin (as in “you can still see where they bolted the train rails to this reclaimed British depot wood that now forms the frame for our bed!”), is just one expression of a profound new horror of space. Amply aware of the sheer social contradiction and cruelty on which the passage of any commodity depends, the last decade has responded with inoculation (the scars of passage tacked to every wall possible) and with a telluric vengeance towards and fixation on whatever can be pinned down to a site.

Circulation pinned down like butterflies

In terms of this full-bore rewriting of urban space and consumer cartography through the look of salvage, speculative culture has been totally, utterly outpaced in both weirdness and force. Unable to clearly distinguish itself from pastiche and unwilling to commit to any rigor of genealogy, torn between being a mere subset of the post-apocalyptic or a defense of “upcycling” and DIY in a prelapsarian world, it ends the only way it knows. Salvage folds in on itself, raising long-graven portraits of recuperated waste that can only and ever look like more of the same, etched in beeswax for the the wall of a craft brewery, black blood for the backdrops of our mordant Kriegsspiel.