The following is an excerpt of my new book Shard Cinema, just published by Repeater. As the project got its start in essays and fragments written here and in conversation with others involved in TNI, I thought it fitting to share a few excerpts over the coming week.

A large part of the book (including its titular shards) comes from grappling with quite recent history, specifically that of the last two and a half decades in moving images. In that span of years, one of the significant and much-noted tendencies is towards the increasing importance of composite images, i.e. those that are constructed by combining a variety of sources, such as 3D animation and green screen footage, and hence that erase the divide between production and post-production. However, a central aim of the book is to show how such images, even the absurdly expensive ones of blockbuster movies, games, and TV that seem to epitomize and celebrate their distance from the circuits and hands of their painstaking construction, cannot be separated from the processes, geographies, and frictions that go into that construction. This, I argue, goes far beyond searching from some indexical trace of a "real world" to be glimpsed, and even further from any banal fetishization of the analog over the digital. Rather, this deep entanglement between image and process lies in the images themselves and the way that what has become their signature style – one that reaches its peak in the slow-motion shards of the title – itself visibly manifests such offscreen processes.

However, while as the book got its start wading through the minor hell of recent 4K chaos, much of it is concerned with the further past (and with other kinds of moving images, especially experimental cinema, photojournalism, military technology, and video games). Specifically, it goes back to some of the earliest images that got designed as cinema in order to understand how new technical and visual forms come to be so normalized as to vanish into quotidian use, even as they remake us in the process – and thereby serve to veil and excuse the social violence that they both require and extend. The most dramatic nineteenth-century instance of this subsumption into and through what feels alien is the factory, and a forthcoming excerpt at Viewpoint details how the industrial transformation of human gestures produced an often unconsidered anticipation of cinema's inhuman animation. In the twentieth century, one of the apparatuses with similar force is undoubtedly the camera, with its slow spread into ubiquity and what I speak of in the book as distributed sight, the diffusion of potential recording into each and every point in space, long before we learned to walk as if ever and always under a shuttering gaze. This excerpt considers a small iteration of this: the way that the camera slips in and out physical presence, in and out of the way of danger's way, and in so doing marks the contours of a politics of and against visibility.]

---

As squatting became a central practice of the radical scene gathering speed in early 1970s Frankfurt, it did so on a terrain whose space had already been imagined anew, gutted, and repurposed – though for markedly different motivations than those driving the critique of the “housing factory” pushed by the Workplace Project Groups. During WWII, Frankfurt’s medieval city center had been thoroughly devastated, the predictable consequence of nearly 16,000 tons’ worth of RAF explosives dumped from on high. This offered a bleakly rare opportunity to fulfill that perennial architectural and urbanist fantasy of the clean slate, and indeed, Frankfurt became one of the few cities in Germany to get a distinctly modernist postwar reconstruction treatment.

That movement should itself be set in a wider framework, one that exceeds the physical occupations and even the explicitly militant rhetoric, as it was unfolding amongst a discordant, seething public discourse about both the city and what constitutes the idea of the public itself. It’s visible, for instance, in the acidly mocking nicknames that Frankfurters were spitting back at their own city, and not in some gentle ribbing of the loved: Bankfurt, and, maybe more cutting, Krankfurt (a pun that might be translated as “sick city”). A city sick with money, feeding on itself in development’s name.

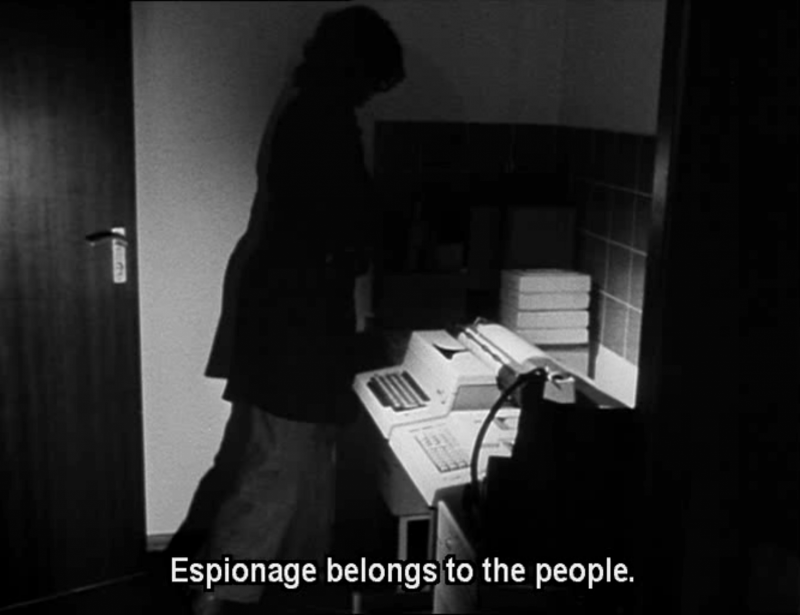

It was on this combative terrain that Alexander Kluge and Edgar Reitz would make In Danger and Distress The Middleway Spells Certain Death, with specific focus on the Frankfurt Häuserkampf (housing battle) of February 1974, zeroing in on the violent eviction of one of those squats prior to the demolition of the building itself, as if to scrub the ground clear of any trace of social possibility. The film is a slippery, fundamentally dialogic hybrid that combines documentary footage of militant resistance and public outrage with the ambulatory wandering of Inge Maier (a prostitute who steals the wallets and cars of her clients), interviews and meetings debating the transformation of Frankfurt’s housing market, preparations for the city’s annual carnival, and a loopy espionage plot that turns on an East German communist spy who insists that “espionage belongs to the people.” (She writes lyrical reports that her contact derides: But you, you write poetry! It’s too general. But class struggle means facts, not generalities...)

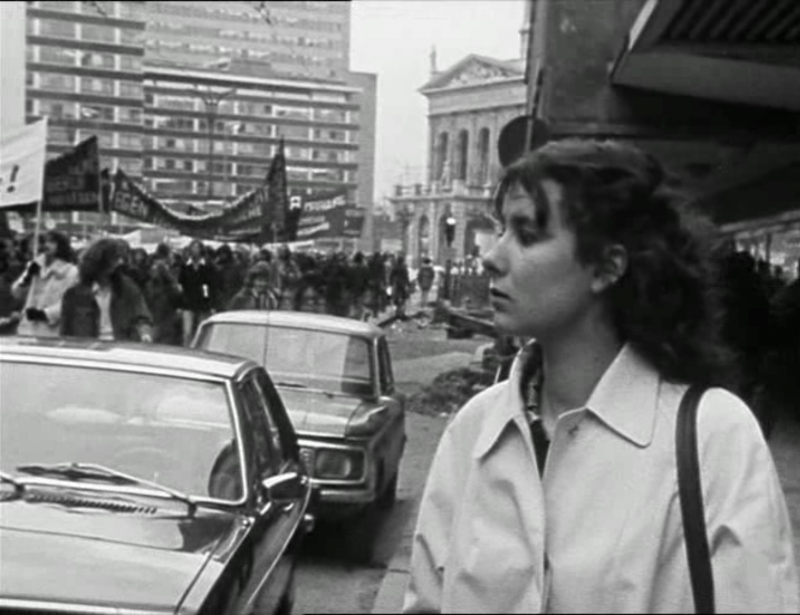

What makes the film remarkable, though, is how it never cleanly delineates these threads but instead tangles them, joining the factual with the whimsical, financial speculation with flights of speculative fancy. The film was intended, in Kluge and Reitz' own words, to produce “proportions rather than statements; an object with which one can argue,” an offer that was certainly taken up, as shooting involved a protracted debate with the squatters whose eviction is filmed, concerning whether or not one can make a film that concerns a struggle that you are not immediately involved in from the start. Perhaps most potently, In Danger enacts this fraught principle of production in front of the lens too, as it intersperses the characters throughout quotidian situations actually happening during the film’s shooting: in an indelible passage, Maier walks, suitcase in hand, through the chaos of the riot following the eviction. The spy, for her part, attends real astronomy lectures, and, at one point, takes a lift high up the outside of the building, looking down and out over the city being transformed by those projects of demolition and construction, surveying it as if a developer or cartographer.

But the shot is intercut in sequence with others of her at street level, carrying out uncertain surveillance of a march against such projects.

And the shots alternate, caught between these two positions and moments without resolve, until suddenly, as though the only solution was to flee plausibility and depth alike, there is a stuffed toy bird that hovers over a rear projection of the city like it’s soaring amongst the skyscrapers, a cut-rate angel of history with cartoon eyes that can't blink in face of the monetized chaos below.

A portion of the riot footage will get reused nine years later, in 1983, to form what has become one of my favorite films ever made, a tiny, precise, and furious two-and-a-half-minute short called Biermann-Film. It’s named for Wolf Biermann, the dissident and resolutely unincorporable folksinger, whose song “Großes Gebet der alten Kommunistin Oma Meume in Hamburg” (“The Great Prayer of Granny Meume, Old Communist in Hamburg”) provides the film’s only sound and dictates its running length, as the images begin in tandem with the song and end when it ends. (The album from which it was drawn, Chausseestraße 131 (from 1968), is itself stunning, an instance of maximal effect from minimal means. Barred from recording in the GDR, the whole record was made with a portable mic snuck in, and so the sounds of the city and his apartment constantly intersperse. Trams and street cars go past and honk, people speak outside, and inside, Biermann simply rages, there’s no other word for it.)

To you I cry as I did in my childhood

My short life was long an abundance of poverty

Oh God, what great toil for a scrap of bread

Formally, the film is exceedingly simple: there is just the song, the riot, and the quiet amidst and after the struggle, as the street is swept clean by those whose job it is to do so, no matter whether the debris comes from a carnival or the daily movement of commerce or an exceptional revolt. It begins with the first line of the song, as riot cops file through our view and line up on the street, identical and interchangeable with their translucent shields and helmets and belted coats, there on a street already strewn with stones as bystanders watch, hands in pockets.

For peace I cried into the great wars

And what have I achieved?

Soon I shall die

I’m fascinated by these drops. By the way I find myself recoiling, as though they’ve leapt through the screen and hit my face. Without any didactic explanation, the film poses a fundamental question that runs throughout cinema: can we be struck by an image?

Because as the lens is hit, the camera suddenly materializes. It becomes something in space subject to being touched and soaked and ruined, and in this collision, this immediate manifestation of what sees, it makes us physically present to ourselves too. We’re at once caught in the mesh of the image and distanced from it, as the mechanism of recording is revealed as a physical apparatus and layer of framing and bracketing, severing any transparent absorption and yet transmitting its shock.

With the distance it has moved, it seems as though some rigid chronometric march of time has kept pace, so that in the seconds filled by that other van, this timeline moved forward undisturbed. Yet the lens is clear. There are no drops on it, no trace of what had happened just moments before.

The image jars and rotates to show the source: another van and its water cannon that has just rolled through, sneaking up to attack anyone, no matter if they are filming. And behind it marches those cops from the beginning, batons out, the way cleared for them.

A quick prayer

But they pass straight by whoever is holding the camera. As if that person wasn’t worth the bother of chasing away or attacking, wasn’t there at all. It’s unsurprising because sometimes the surest way to remain unseen is to record what you are seeing, to hold a camera in front of your face. Because whatever can get soaked and keep filming, whatever has sight that can be magically cleared of any liquid or interference like nothing happened, is something that promises to not touch back, to not intervene, to mind its own business, to barely be there in the first place, just a record, a ghost and its machine.

Towards the end of the film, as the song is hitting its climax, Biermann belts out, voice furious and shaking:

Oh God, grant that Communism triumphs!

Grant that my beloved Wolf does not end up

Behind barbed wire as his father did

At this moment, the camera is looking up at the sky past a building, as though echoing the addressee of that prayer, the “God in heaven” to whom Biermann sings also the first line of the song. There are kids arrayed on top of the buildings, and the air is bright and clear, with fluffy and decidedly unmenacing crowds. One might read this alignment as an affirmation of faith, that all one needs – or can – do is pray and wait for someone in the sky to handle the undoing of capitalism or at least to strike down the cops from above. But that’s not what the film thinks, remotely, especially given that prior to this, we see that someone inside one of the surrounding buildings has got water of their own and is hosing the cops away, chasing them off.

Besides, that very same line was sung with equal fervor at another point in the film: right when the water splattered the lens, the last word falling dead on the instant of impact. That’s the counterpoint, the film’s grasp of the kind of messy contact and interference at work in the process of dismantling capitalism. Not the utopian dream or the prayer to the endlessly far, but the point at which any fantasy of remove or distance is ruined, and no one gets to be innocent or simply an observer, when even the camera itself can’t be excused for its complicity and can be touched, wetly, fine with the mist of the riot.