Of the various impressions made on the English man of letters Joseph Addison during a 1702 visit to a Freiburg monastery, one that lingered longest was the delight its inmates took in eating snails

And day's at the morn;

Morning's at seven;

The hill-side's dew-pearl'd;

The lark's on the wing;

The snail's on the thorn;

God's in His heaven --

All's right with the world!

-- Robert Browning, song from Pippa Passes (1841)

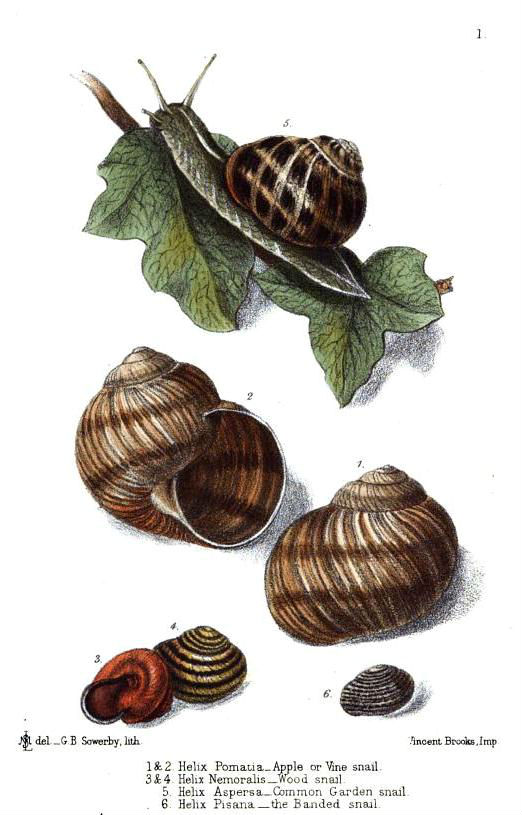

On the supposed uniqueness of the Freiburg monks' escargotieres Addison proves an unreliable source; one could find versions in Brunswick, Silesia, Copenhagen and other locales. Their design varied by region. The people of Barrois used staved in casks covered with netting. The snails of Lorraine endured a somewhat more picturesque imprisonment: a quiet garden corner stuffed with leafy matter and encased in fine trellis-work. The earthier escargotieres of Dijon consisted of trenches dug by vine growers. Into these they dumped leaves, then snails, and then more leaves before topping everything off with few spadefuls of earth. Voralbergers, who combined gastronomy with good husbandry, preferred their snails free-range. Children made a game of searching farmers' fields for the tasty pests, which they plucked from lettuce leaves and cornstalks in a bid to see how many they could contribute to the town escargotiere, usually a large plot of land encircled by a moat. These summer games yielded a great harvest: The enclosures contained often some 30,000 snails fattened on cabbage leaves and kept damp by twigs of mountain pine and small clumps of moss.

How snail aficionados, or heliciculturists, cooked their snails varied as much as how they kept them. Some stuffed them with forcemeat, while others steamed them with rice or boiled them in the shell before slathering them with drawn butter and sprinkling them with parsley. Whatever the method, simplicity ruled; snails were typically eaten during Lent. Indeed, a dish of these shelled savories traditionally marked the end of Carnival in Canderan, a town near Bordeaux. What the snail growers didn't sell they shipped off to convents and monasteries. What the monasteries didn't eat, they gave to the poor. The "hero who carries his house on his back," as Hesiod called the snail, could expect life to describe an odyssey that, no matter the length, arrived at the same destination -- the plate of some hungry soul.