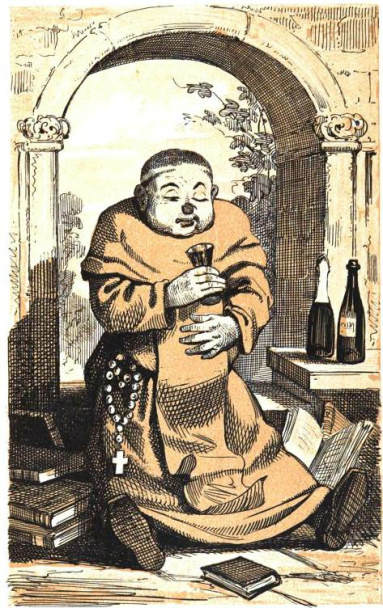

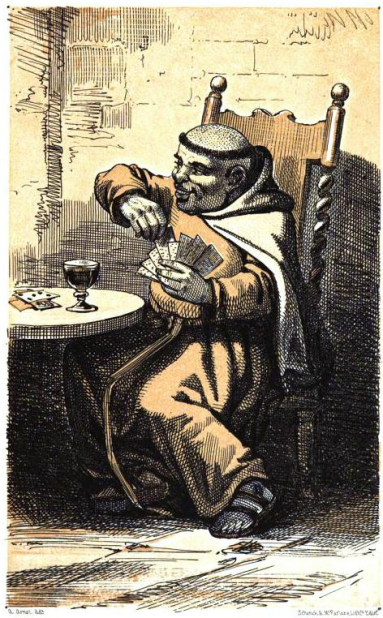

A stay at a medieval monastery often featured a lavish meal hot from the friar

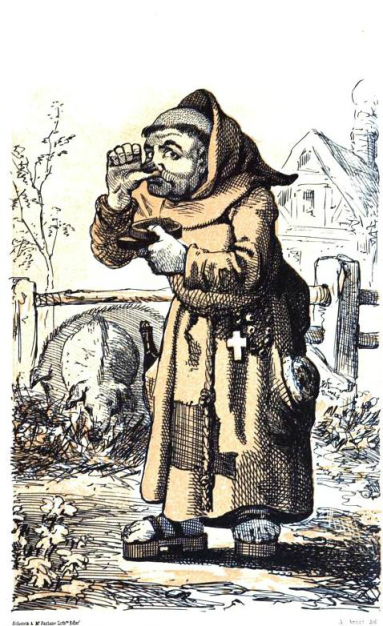

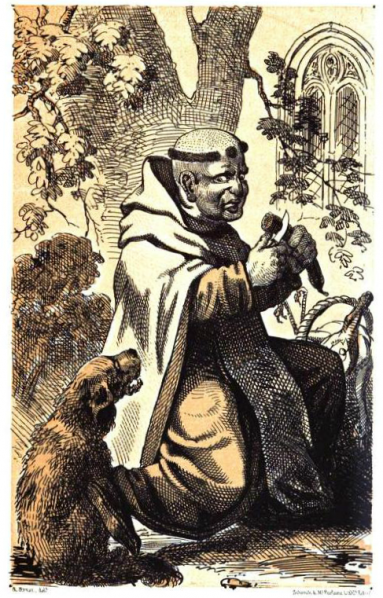

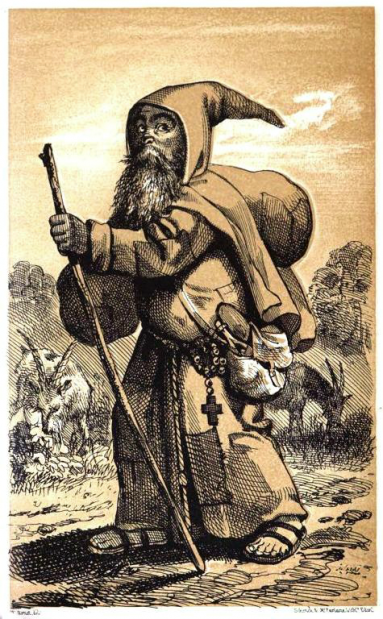

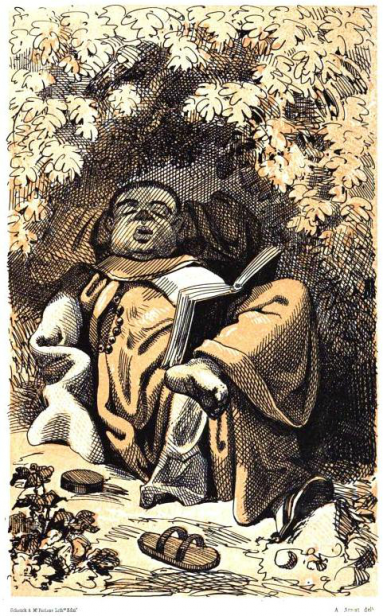

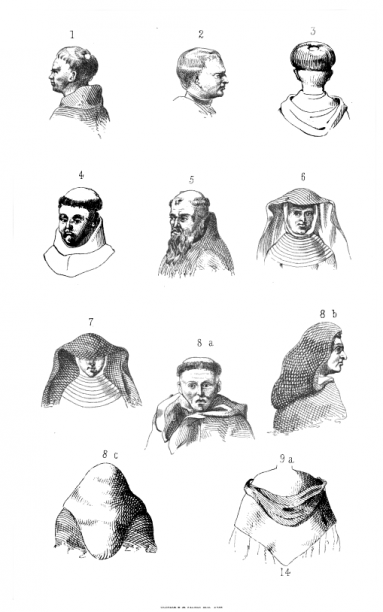

Illustrations from Monachologia: Or, Handbook of the Natural History of Monks, Arranged According to the Linnaean System (1852)

Vogelweide chalked the monks' inhospitality off to misunderstanding. They likely did not mark his regal bearing, so busy were they transcribing the Ancients and painting miniatures, work for which their cloister was famous. "I blame them not," he later wrote in a poem he entitled "The Inhospitable Cloister." "God grant us both His grace!"

During a trek through the Bavarian Alps, German troubadour Walther von der Vogelweide paid a visit to the famous cloister of Tegernsee. Its monks, rumor had it, served sumptuous dishes, decanted excellent wine, and generally entertained in grand style. The day was hot, his exertions great. The poet reached Tegernsee monastery's gate keen on refreshing himself. Yet no sublime vintage, no comfits and sweetmeats greeted him. He received a carafe of lukewarm water, and nothing besides.

"He led us to our cells in the pilgrims' hospice. Or, rather, he led us to the cell assigned to my master, promising me that by the next day he would have cleared one for me also, since, though a novice, I was their guest and therefore to be treated with all honor." --Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose (1980)

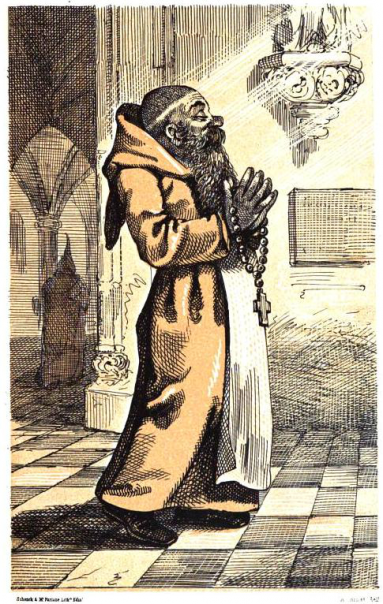

That this reception left Vogelweide disappointed one cannot doubt. The principle of kindness to strangers held such sway that well-intentioned wayfarers expected a hot meal and warm bed wherever they happened to stop. This was no more true than when wayfarers visited one of Christendom's many monasteries, where piety and solemnity did little to discourage conviviality and good cheer. These monasteries turned no one away; they welcomed everyone, regardless of wealth or status. Princes might sleep down the hall from beggars, merchants might dine with priests. And when they did, they did so gratis.

Monasteries did not admit all visitors. Some forbade royalty from spending the night, while others disallowed female guests.

The state of peace among men living side by side is not the natural state (status naturalis); the natural state is one of war. --Immanuel Kant, "Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1785)

Conditions during the early Middle Ages made such hospitality necessary. Inns were scarce, roads treacherous. Whatever taverns did exist were usually filthy, dubious establishments; and the muddy, rutted thoroughfares of the premodern world seemed to harbor nothing but bandits, tricksters, beggars, knights errant, and other assorted scapegraces. The lucky soul that found his way to the monastery gates could truly claim to have been borne there by Providence.

The four kinds of monastic bread: panis armigerorum, a white bread for the abbot's guests and wayfarers of distinction; panis conventualis, darker bread eaten by the monks themselves; panis puerorum, served to the boys of the cloister school; and panis famulorum for the lay servants of the monastery.

Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Western monasticism, decreed in his Rules that there "ought in the monastery to be suitable places where guests can be welcomed respectfully and cheerfully."

Lucky for him also was the fact that the monastery's residents delighted in unexpected guests, whom they met with an effusive greeting that began with a kiss of peace and washing of hands and feet before proceeding to prayer and culminating in a rich repast. Along with good cheer the monks heaped on their visitors roast pigeon and hare, egg-thickened porridge, great planks of salted salmon, mounds of glittering whelks, fillets of bream and lamprey, thick porpoise steaks, and other fruits of sea and lake. Vegetables fresh from the monastery's garden arrived at table, as did fruit from its orchard. And bread, loaves and loaves of bread: Four kinds the monks had, from black to white and every shade between.

"You utter a vow or forge a signature and you may find yourself bound for life to a monastery, a woman or prison." --Bronislaw Malinowski

Though St. Benedict may have forbade his monks to eat creatures having feet, many abbots turned a blind eye when on plates should appear suckling pig, roast goose and other delights. Abbot Samson of Bury St. Edmunds went so far as to employ hunters to supply his monastery's guests with fresh game. Monks were even known to catch frogs and beavers for eating. Plucked from pond and stream, these web-footed things, they insisted, were more fish than flesh. They similarly concluded that laurices, or newborn rabbits, were more egg than animal. Their consciences assuaged by such scholastic reasoning, they devoured these creatures by the dozen.

"Go on betimes, loiter not as a guest ever in our abode; / He, though loved, becomes burdensome, who warms / himself too long at hospitable fires." --Edda (ca. 13th century)

For those who wished to dine neither on beaver nor bunnies, monks' vegetarian fare presented an ample substitute. A traveler staying at a Trappist monastery in France recalled dining on fruit, a few vegetables, a hunk of cheese, a loaf of bread, butter and some sweets. He found the meal delicious. But pity the traveler who showed up during Lent at the gates of the most austere orders; he often received only bowl of lentils and oats for his trouble.

As welcoming as medieval monks were, the ancient Greeks were more so. Some say they set the standard. Kindness to strangers was for them a way of life; to abuse the wayfarer was to court divine wrath. Zeus protected strangers and supplicants, and a Greek never knew if the traveler knocking at his door was the god himself in disguise; he well-remembered the tale of Baucis and Philemon, that kindly couple who entertained, unawares, the gods in their humble cottage.

Yet no matter how self-denying the order, the traveler could count on it to produce a cheering cup. Most monasteries brewed and fermented with gusto. It was said that the ale made by the Benedictines of Orgeval so delighted the palate that, on once occasion, it inspired a group of young men to join the order. And where climate permitted, monks made wine as well. Canterbury Church and St. Augustine's monastery in England boasted several vineyards. The Isle of Ely was renowned for its vintage. All throughout Europe monasteries crafted such surpassing spirits that even kings paid them visit to sample a dram.

Villagers of St. Riquier of Picardy had to provide their monastery each week with 100 loaves of bread, 30 gallons of tallow, 60 of ale, and 32 of wine.

A recipe for Monastery Wine Soup from Cassell's Dictionary of Cookery (1883): "Pick and wash four ounces of good rice, put it into a saucepan with a pint and a half of cold water, and the yellow rind of a lemon. Let it soften gradually, and when it has become quite tender, pour over it a pint and a half of any white wine, and stir in from three to four ounces of sugar. Beat the yolks of four eggs, pour the soup slowly upon them in the tureen, and serve at once."

On the whole, happy was the traveler who landed in a monastery. He ate good food and slept in a soft bed. But it was those the traveler passed on his way to the monastery who often bore the cost of his night's entertainment. Though clever and industrious, monks were not wholly self-sufficient. They depended on the toil of people who lived and worked beyond their cloisters' gates. On fairs and markets they levied dues. They controlled local bake-houses, mills, wine presses and stud bulls. From farmers and artisans they demanded tithes, and, where permissible, they owned serfs. No mere Peter's pence, such exaction burdened folks who in most cases lived at or slightly above subsistence. Indeed the old rules of hospitality were such that a free lunch often meant someone went without supper.