A helping of Halloween heebie-jeebies from The Ghosterity Kitchen

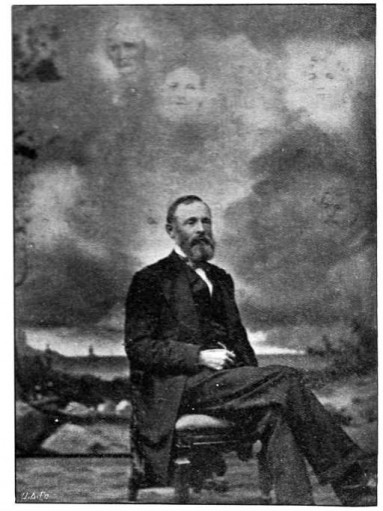

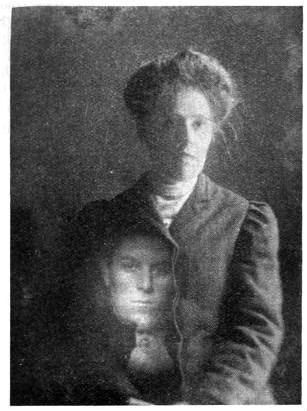

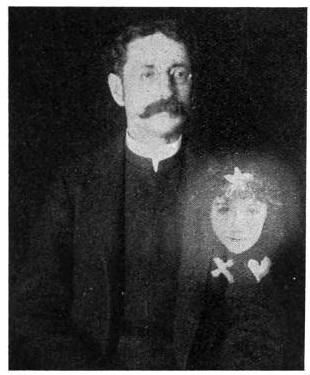

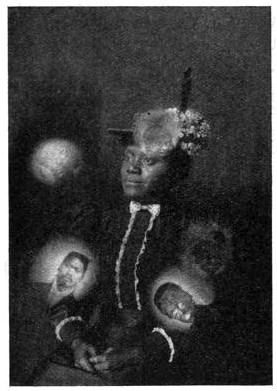

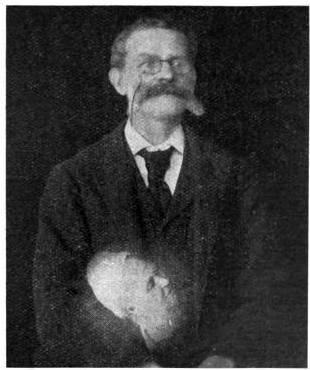

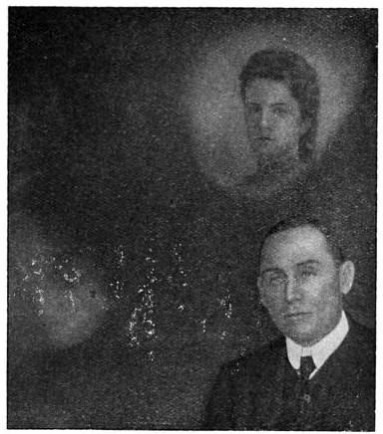

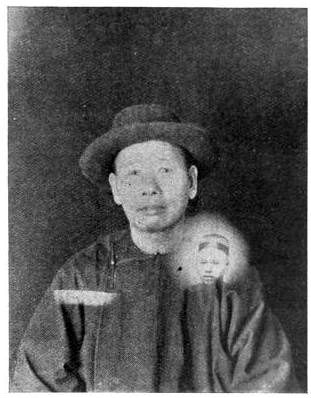

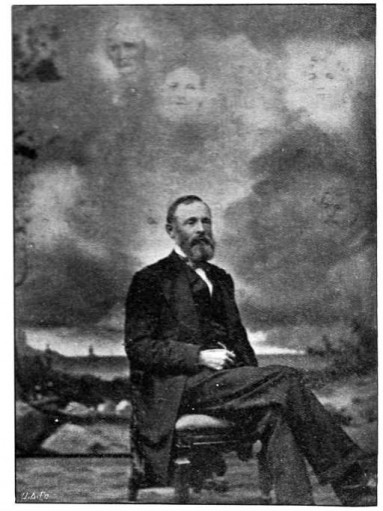

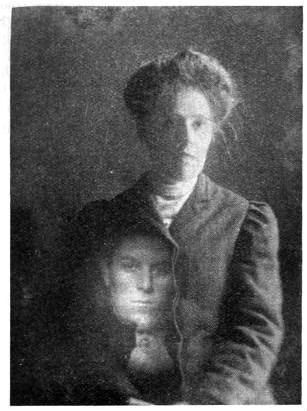

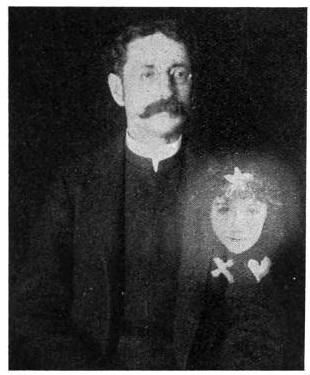

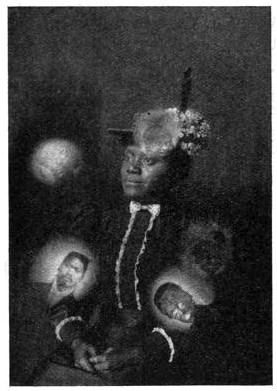

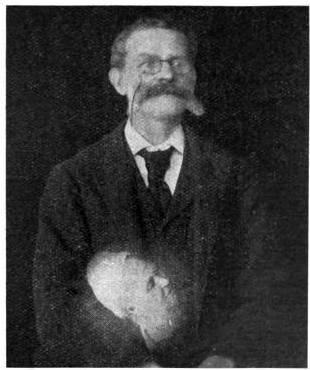

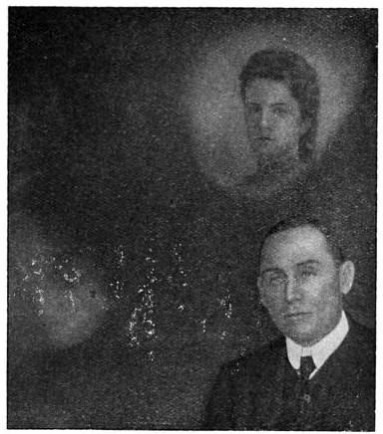

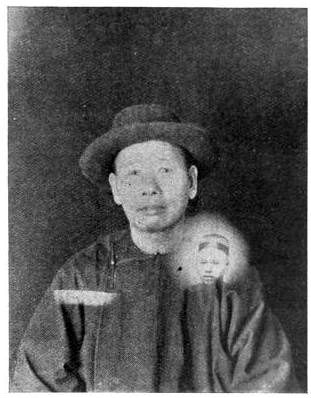

Photographs from Photographing the Invisible: Practical Studies in Spirit Photography, Spirit Portraiture, and Other Rare But Allied Phenomena (1911)

When asked by his disciple Crito, "Where shall we bury you?" Socrates replied, "Bury me just where you please, if you can only catch me," and then added, "Have I not told you and the wise men that the body is not Socrates?"

Emanuel Swedenborg arrived famished to a London inn late one April night in 1745. The dinner set before him he devoured, pausing only to savor its aroma. "How pleasant the food smells!," he remarked. “How wonderful the flavor!" After cleaning his plate he sank back in his chair. "I've never enjoyed a meal more," he sighed.

The Swede's enjoyment quickly turned to horror. A strange languor overtook him. His vision grew hazy and he felt himself held fast to his chair as if by powerful invisible hands. From his pores issued a vapor. Snakes wriggled and frogs flopped at his feet. In one corner of the room appeared a shadowy figure. "Eat not so much," it commanded and then faded away.

Swedenborg maintained that the dead clad themselves in the clothes they had been accustomed to wear, and that they ate and drank, lived in houses and towns, and continued with most of their earthly habits.

"Perhaps they are not stars, but rather openings in heaven where the love of our lost ones pours through and shines down upon us to let us know they are happy." --Eskimo saying

Swedenborg obeyed the figure's command. For the rest of his life as a celebrated mystic, a career some say he began that very night at the inn, he observed an austere diet of bread, milk, and coffee. In this he was not unique. Because things mystic and gastric so often commingled, seers of all stripes hewed to one dietary regime or another.

They had good reason to do so. Swedenborg's celebrity sparked a fad for communing with the dearly departed. German philosopher Immanuel Kant dismissed Swedenborg as "a spook hunter," but not before he read all eight volumes of the mystic's Heavenly Mysteries. Napoleon claimed to be visited often by a ghostly "little red man" whose gloomy premonitions he took to heart, and Czar Alexander II wined and dined spiritualists in grand style. Poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning's fascination with the undead so annoyed her husband Robert that he felt moved to pen a satire entitled "Mr. Sludge, 'The Medium.'"

"All was not cheating, sir, I’m positive! / I don’t know if I move your hand sometimes / When the spontaneous writing spreads so far, / If my knee lifts the table all that height, / Why the inkstand don’t fall off the desk a-tilt, / Why the accordion plays a prettier waltz / Than I can pick out on the piano-forte..." --Robert Browning, "Mr. Sludge, 'The Medium'" (1864)

Alexandre Dumas

fils received a visit from none other than dear old Dad, who bade him be "a good boy and love your mother." Defending spiritualism became something of a cause for German philosopher I.H. Fichte, who no doubt had something like the wisdom of Victor Hugo in mind to spur him on his crusade. "Those that depart still remain near us," wrote Hugo. "Sweet is their presence: holy is their converse with us."

"Signor Damiani then, in answer to a series of questions, said that he had learned from the spirits that there was no distinction of rank in the other world. It was a regular republic -- a democracy." --From the Report on Spiritualism: Of the Committee of the London Dialectical Society (1873)

"All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses, / And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier." --Walt Whitman

In time, the yen for holy converse reached America’s shores. In 1848 the teenaged Fox sisters began hearing rapping sounds in their Hydesville, New York home. They replied in simple code, ending each message with the command, "Hear, Mr. Splintfoot, do as I do," their correspondent a 31-year-old man murdered some five years before. By the time the sisters got up the nerve to root around the premises for the victim's bones (these along with a few teeth they reportedly found), the entire Eastern seaboard was abuzz with tales of ghostly knocking. The messages often proved timely. Spirits contacting Abraham Lincoln rapped their demand that the country's four million slaves be freed. Harriet Beecher Stowe had dictated to her from beyond the entire text of

Uncle Tom's Cabin. As perhaps only befitted one whose mind could conjure a headless horseman, Washington Irving found the raps reaching his ears a comfort. He claimed they were proof that "those we once loved [are] permitted to return and watch over our welfare." Longfellow echoed this sentiment. The avenues to those loved ones lie "all about us," he believed.

"The real question of life after death isn't whether or not it exists, but even if it does what problem this really solves." --Ludwig Wittgenstein

"Ouija board, ouija board, ouija board / Would you work for me ? / I have got to get through / To a good friend / Well, she has now gone / From this Unhappy Planet / With all the carnivores / And the destructors of it." -- S.P. Morrissey, "Ouija Board" (1989)

"A spirit answered, 'Yes, I am Dr. Livingstone.' I then asked him how he had been killed, and he related all the particulars. He said that a native had crept up behind him, and given him a blow of a club on the back of the head, and killed him outright at once. I asked what happened then, and the spirit said that the savages boiled his body and ate it. I said, 'That was horrible! You must have been greatly horrified by your body being boiled and eaten.' He said, 'No; I was not horrified at it, for we must all be eaten.'" --From the Report on Spiritualism: Of the Committee of the London Dialectical Society (1869)

Though some among the dead preferred to address living relations, many chose to speak solely through mediums. Strange souls, mediums were a breed apart. Feeble-minded females who avoided meat made the best ones. Indeed, vegetarianism was deemed essential to the vocation. Members of the Theosophical Society felt it furthered their cause of promoting the "universal brotherhood of man," living and deceased. (The society’s founder, Helena Blavatsky, however, may have privately held a different opinion. No ascetic herself, her corpulence was such that she had to be hoisted aboard ships and other conveyances by a chair attached to a rope and pulley.) Other spiritualists likewise found that herbivory helped them commune with all creatures great and small. "The vegetarian diet is the most favorable to purity, chastity, and to perfect control of the appetites and passions," opined R. Swinburne Clymer, who enjoined "all true Spiritualists and Mystics" to do "all in their power" to abolish meat-eating, which he thought a "horrible crime."

"In demonstrating the fact of a future life, I have simply analyzed the mental organization of man, and shown that, from the very nature of his physical, intellectual, and psychical structure and organism, any other conclusion than that he is destined to a future life is logically and scientifically untenable." --Thomas Jay Hudson, A Scientific Demonstration of the Future Life (1903)

Vegetarian or no, mediums seldom enjoyed an uninterrupted meal. Astronomer and philatelist James Ludovic Lindsay recalls a dinner he once shared with renowned medium Daniel Dunglas Home. No sooner had everyone tucked into the first course than "a chair came up to the table with a rush." A series of faint raps followed. The table then began to vibrate before rising some 15 inches, making finishing the soup course impossible. The raps continued, meanwhile, growing from faint to thunderous. Rays of color emitted by a crystal ball formed a vision of the sea as seen from a high cliff. In a ghostly sky stars twinkled.

"Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them." --George Eliot

"From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity." --Edvard Munch

"If anybody would endow me with the faculty of listening to the chatter of old women and curates in the nearest cathedral town, I should decline the privilege, having better things to do. And if the folk in the spiritual world do not talk more wisely and sensibly than their friends report them to do, I put them in the same category." --T.H. Huxley

Visions ran the gamut, appearing heavenly one night, hellish the next. A dinner party given by a medium named Moser saw its host seized by a disturbing presence. Taking up pen and paper, a possessed Moser drew a horse and truck. Below these he scrawled, "I killed myself --- I killed myself to-day -- Baker Street ... killed myself to-day under a steam roller." An article in that evening's edition of the

Pall Mall Gazette later established Moser's vision as fact: A man had flung himself down before an approaching steamroller that bore an image of a horse.

Investigations into spiritualism by Micheal Faraday and William Carpenter found that, in the case of table movements and rapping, force was exerted, but subconsciously so.

As elated as a convincing spiritualist could leave witnesses, a dubious one could leave them flat. Frauds abounded. One British medium's powers, it was discovered, owed to nothing more than some muslin, a bottle of phosphorus, and a fake beard. The "spirit hand" of another medium operating in Boston turned out to be a cleverly carved piece of animal liver. In Berlin police wrestled a medium to the ground and pried from her petticoat items that would materialize during her séances -- some 157 flowers and a few dozen oranges and lemons. And in 1888, Margaret Fox appeared before an audience to demonstrate how she produced spirit rapping by cracking her toe joints. An essay she later published in the

New York World contained the bald assertion, "Spiritualism is a fraud and a deception." Renowned Victorian illustrator George Cruikshank did Fox one better by imputing malicious intent to the trickery. He insisted that a "large and serious amount of suffering and injury" resulted from "belief in ghosts."

Recipe for Halloween Fudge from St. Nicholas, Volume 36 (1909): "Sugar and milk together boil / Until in water cold / They make a soft elastic ball / Between the fingers rolled. / Remove at once from off the fire; / Let stand until lukewarm / Where no rude jar nor shaking up / Can do it any harm. / Then beat to the consistency / Of good, rich, country cream; / Vanilla add and cinnamon, / And butter's golden gleam. / Salt, nuts and ginger stir in last; / Pour all in buttered pan; / When cool and hardening, cut / In squares, as many as you can."

"I believe that when death closes our eyes we shall awaken to a light, of which our sunlight is but the shadow." --Schopenhauer

Whether gulling harmed those gulled is difficult to know. Suffice it to say that being taken in by a clever faker rates as one of the lesser injuries a body might suffer in the 19th century. Injurious or not, spiritualism fascinated Victorians. By 1897 more than 8 million people in the United States and Europe professed to be spiritualists. The movement's popularity poet Gerald Massey attributed to its power to "make religion infinitely more real" by translating "faiths into facts." For an age enamored of science, spiritualism offered skeptical minds irrefutable proof of an afterlife. That this proof was often ridiculous mattered little. Against glimpses of a luminous, more meaningful future existence, present material reality didn't stand a ghost of a chance.