A photograph from Margaret Warner Morley's The Carolina Mountains (1913)

The moonshiner treats strangers with suspicion. Rarely do they visit his mountain shack, and rarely does he visit town. He isolates himself among mountain and valleys, which he leaves only once or twice a year. When a batch of corn mash has fermented, he distills it into "mountain dew" strong enough to make eyes water and throats burn. Barrels of this he packs in his wagon under hay and overripe apples (their scent masks that of the liquor) and winds his way over rocky, narrow paths to market.

Inspiration for this post comes from Emil O. Peterson's "A Glimpse of the Moonshiners" (1898)

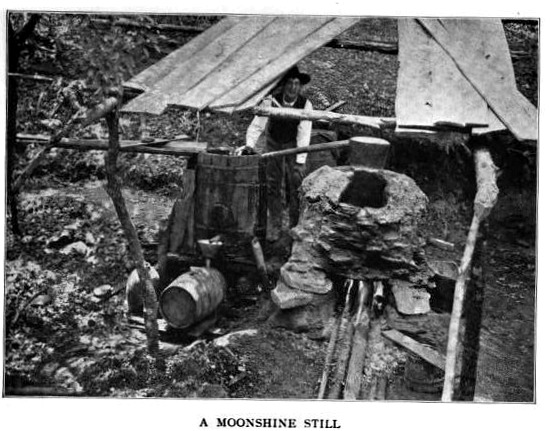

Stashed among bushes, perched over a stream or lashed to the side of his shack, the moonshiner's still performs it mute alchemy. The clear gold it transmutes from dun grains reliably commands such healthy profits that it quickly becomes the single most important item in its owner's life. Indeed, an aggrieved moonshiner doesn't seek revenge on another moonshiner by attempting to injure that moonshiner or insult that moonshiner's wife. Rather, he reveals to the police the location of his rival's still. Revelation of this trade mystery invariably proves devastating. Financial ruin, and sometimes death, soon follow.

"Too cheap are wine and love," complains the character Euclio in Plautus' The Pot of Gold (ca. 195 BC), "if one in liquor and in love is allowed to do with impunity whatever he pleases."

The Boston Cooking School Magazine (1911) contains this recipe for squirrel pie: "Have the squirrels carefully cleaned and singed. Separate into pieces at the joints, nine in all. Put these in an earthen dish; add salt and pepper and one pint of boiling water or highly seasoned meat stock, cover the dish and let cook in the oven about two hours, or until tender. Stir in two or three tablespoonfuls of flour, half a teaspoonful of salt, and half a teaspoonful of pepper, mixed smoothly with cold water. Continue stirring until the sauce boils. Remove from the oven to cool a little while the crust is made ready. Roll the crust to fit the dish. Have it one-fourth an inch thick, if made of pastry, half to three-fourths an inch, if made of biscuit dough. Make a slit for a 'vent' in the center and cut out a few figures from the paste as ornaments for the crust, when it is set in place. Brush the edge of the dish with cold water, set the paste in place, trim neatly, brush the bottom of the ornaments with cold water and set them in place. Bake about twenty five minutes. Serve hot with brown or tomato sauce, to which mushrooms may be added. Pass at the same time celery salad and quince or black currant jelly.

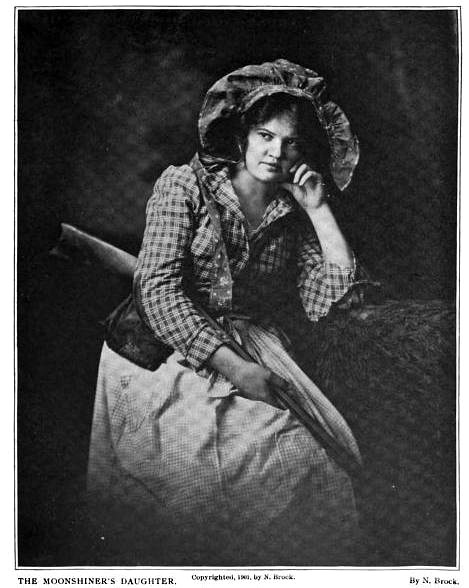

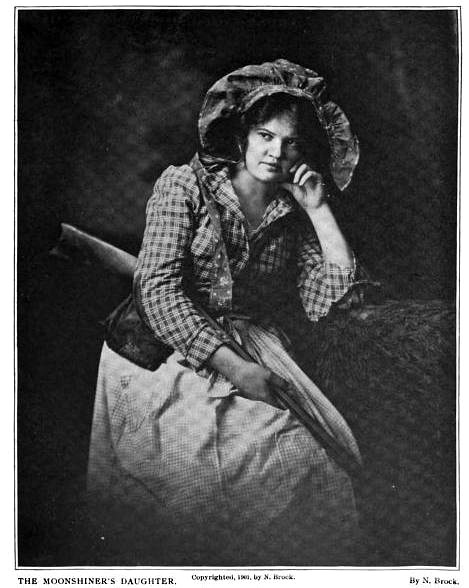

Occasional vendettas notwithstanding, moonshiners generally conduct their lives peacefully. At those rare times when folks pay him a visit, he plays the generous host. He delights in good company and lives in expectation of one great yearly festival: the season of camp-meeting. Held in various places from mid-August through October, this open-air revival sees all the moonshiners gather, with tents and families in tow, for a week-long jubilee. Each evening they gather around great fires and sing hymns into the wee hours. During the day, men swap recipes for moonshine mash or tips for evading the law while their wives and daughters laugh and gossip, catching up on news from elsewhere in the region. The married among them show off their finest clothes while the unmarried keep an eye open for handsome bachelors or comely maidens. Young men drive around in two-horse wagons, scooping up the prettiest girls and trundling them off to nightly farmhouse balls. There they caper through cotillion exercises known as "twistifications" and refresh themselves with generous quantities of mountain dew.

N. Brock, "The Moonshiner's Daughter" (1900)

The rest of the year the moonshiner passes in comfortable quiet. Only one enemy has he: the revenue officer. Of this bogeyman he lives in mortal fear, and he stands ready to greet him with a shotgun loaded for bear. In the balance hangs his livelihood and his very life; the state can take his land should it see fit to do so. Many a standoff between moonshiner and revenue officer end in bloodshed. More than anyone, then, the moonshiner appreciates the only two certainties in life, death and taxes.