For those readers not fluent in the often arcane nomenclature of popular-music taxonomy, yacht rock refers to a style of post-Altamont soft rock ascendant throughout the 1970s that sterilized the form of its soul and blues elements and instead emphasized disinterested, intentionally trite lyrical themes and an almost nonchalant instrumental virtuosity or "smoothness." Given the postautonomist implications of virtuosity, one can see why the Jacobin was inclined to yoke yacht rock to neoliberalism. But the Jacobin's critique overlooks the agency of the highly flexible and frequently autonomous studio wizards who developed yacht rock, choosing to view them as the hapless pawns of reactionary Reaganism ("Yacht rock was scavenged from various sixties casualties") and writing off their immaculate commitment to craft as passionless "blandness."

The Jacobin would have you believe that "yacht rock was an escape from blunt truths, into the melodic, no-calorie lies of 'buy now, pay never,' in which any discord could be neutralized with a Moog beat," but this glib dismissal overlooks the particular nexus of cultural and ideological forces in which yacht rock emerged, and the way in which the genre functioned to imagine a plausible utopia and thereby reinvigorate the will to resist. The Jacobin mistakes the necessary prerequisite of believing an escape from capitalism is possible for the exercise of mere escapism.

Yacht rock was, in fact, pivotal in the etiolation of pop music in a time of cultural darkness, serving as a dialectical pole to progressive rock as well as to punk, postpunk and even proto-postpunk, spurring drastic retrenchments. Yacht rock was an ameliorative adaptation to the 1970s malaise, not a cause of it. The Jacobin accuses yacht rock of co-optation, but its borrowing was tactical rather than reactionary, a series of clever maneuvers of a cultural workforce threatened with obsolescence to outwit capital under the guise of collaboration, striking a bargain that retarded the subsumption of artistic forms and bought the emerging generation of youthful musicians a hiatus in which to prepare resistance. Yacht rock arrested the conquest of cool, establishing for perhaps the last time a cultural Maginot line of anticool that was capable of stalling the imperial progress of fashionability. If yacht rock was counterrevolutionary, it was in this sense, opening up a space in which the popular was not subservient to the status games of coolhunting and the disciplinary function of novelty.

With the failure of overtly political forms of protest music, which by 1970 had become fully co-opted for the production of status distinction and "cool," the forward-thinking music-industry veterans who had been responsible for propagating the possibilities of pop participation as a mode of refusal of the status quo were forced to retrench. Betrayed by the record labels who facilitated the grand sell-out and made rebellion and consciousness-expansion into mere commodities, rank-and-file culture-industry agitators like David Crosby hit upon the cunning strategy of disguising their attacks on capital in product that foregrounded formal fastidiousness over explicit sloganeering. Rather than generate new anti-establishment symbols that inevitably expanded the terrain of the establishment once they were co-opted, the new approach would embrace placid insularity.

If one's music was doomed to be appropriated, why not start with a bold appropriation of one's own? Yacht rockers pose in the guise of capitalism's traditional expropriators -- the leisure-class layabouts, the rentiers, etc. -- only to model the empowerment of the expropriated not via a pity-charity program of redistribution under conditions that will continue the cycles of immiseration but via a queering of the very notion of indulgence. Rather than capital indulging workers by affording them the means of subsistence, workers appropriate the forms of indulgence, exploding the oppressive mechanisms of leisure by pursuing its fantastic logic of superfluity. Pleasure for all, not just for those with the habitus sufficient for detecting the opportunity of it in hurling insults at aesthetic inferiors.

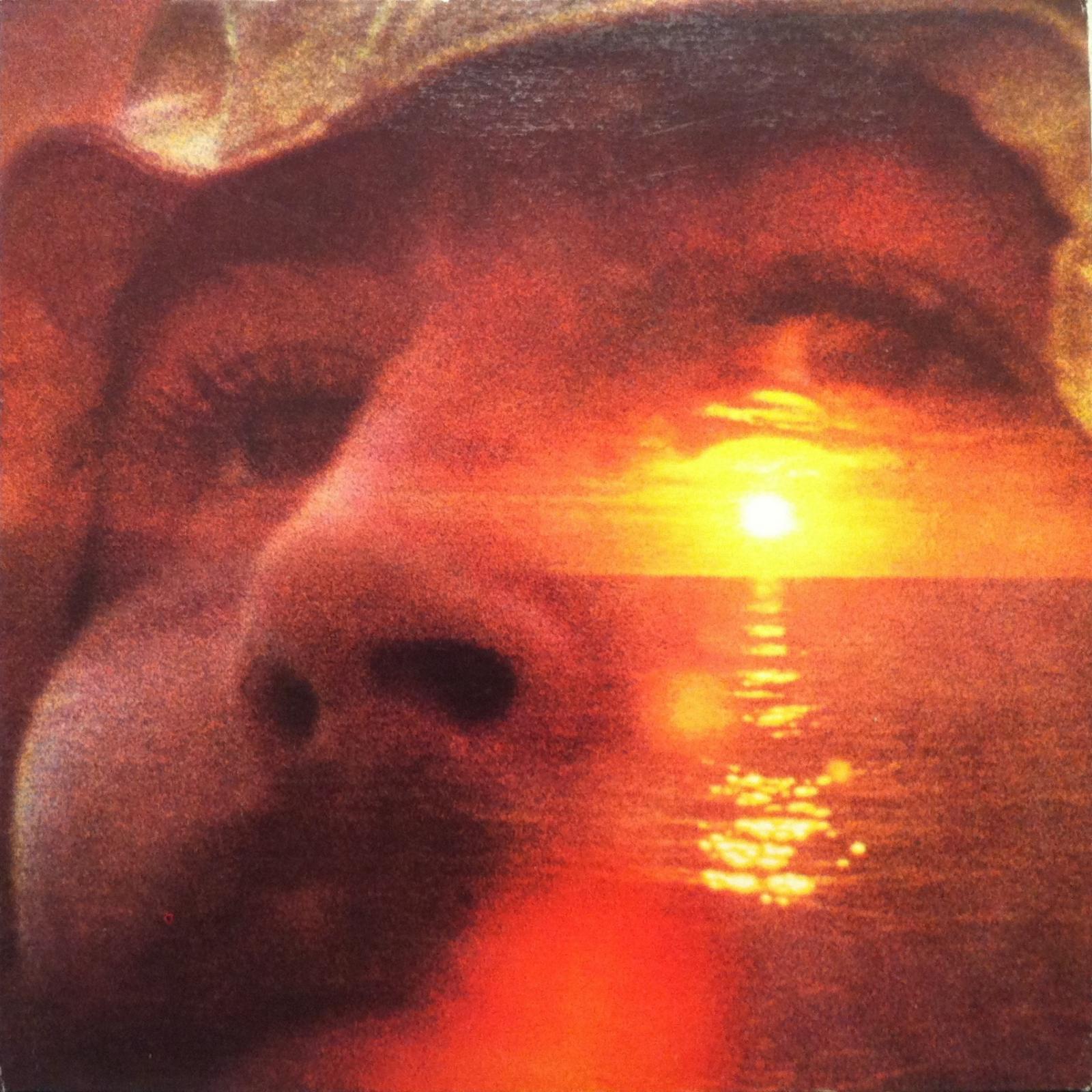

The title of Crosby's first solo album telegraphs the nature of the new political strategy: If I Could Only Remember My Name. In place of the strident assertion of one's vanguard opinions and prescriptive political demands, Crosby and his army of fellow travelling celebrity rock musicians would efface identity, pursue self-forgetting through a hermetic and featureless "smooth" music. Crosby's successors, yacht rock's faceless antiluminaries -- Steely Dan, Seals and Crofts, Poco, Christopher Cross -- would produce the negation of the mainstream and the "popular" as such, razing the ideological ground the more self-consciously subversive genres predicated their identity on being able to claim.

Instead of the rationalized production of "cool" and novel lifestyle tropes that the late 1960s unleashed, yacht rock turned to aggressively uncool and retrograde signifiers of achievement: yachts, sailor caps, tropical getaways, tans, state-of-the-art audiophilia -- exhausted symbols that could be recuperated only as carnivalesque parody. By de-emphasizing identity, innovation, and novelty, yacht rock re-imagines luxury's abundance as inclusiveness rather than scarcity, a mode of enjoyment by rights open to all and offensive only to those snobs who predicate their pleasure on feelings of superiority. It unequivocally rejects the productivity of connoisseurship in favor of a taken-for-granted democratic lexicon of public-domain cliches of the good life.

Yacht rock targets those cultural fucntionaries who carry water for the leisure class by enforcing not any particular set of tastes but the very notion that taste should regulate one's social deserts and serve as an index to one's social worth. It seeks to sever the link between music appreciation and status by rendering the popular into the smooth.

The smooth in yacht rock served as a kind of sonic fracking fluid, injecting itself into the interstices of the capitalist integument to blast it asunder. It supplanted the repressive tolerance of allegedly transgressive music with a truly liberatory anality. By affording no new iconography of self-aggrandizement to listeners, yacht rock permits them the only form of pleasure possible when all modes of everyday self-expression have been subsumed and expropriated by capital as forms of brand-equity enrichment. It allows listeners to disappear into the "bland," the uncool, the anonymous, the faceless, and sail away.

The Jacobin is right to proclaim that "it is only through the cultural transmission of social solidarity – and the rejection of empty celebrations of oneself – that neoliberalism can begin to be annihilated." But no celebration of the self is more politically impotent than the hollow self-congratulation of the sarcastic and secretly shame-ridden music trend chaser who marches in double-time to fashion's inexorable drumbeat and calls his desperate pursuit of exclusive and personal cultural capital a form of radical critique. That's what a fool believes.