Bad food and lousy beds didn't keep early American taverns from turning a tidy profit

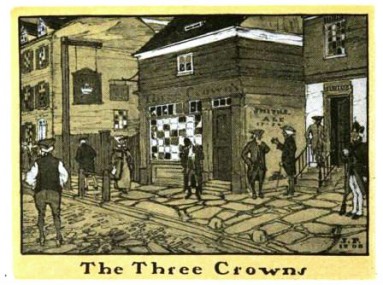

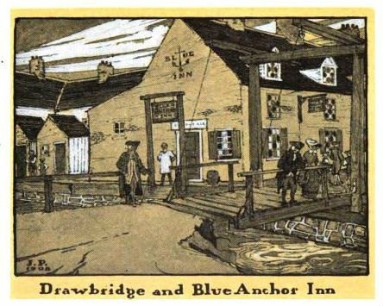

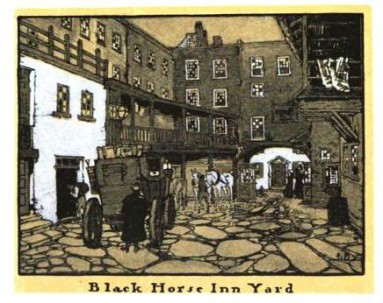

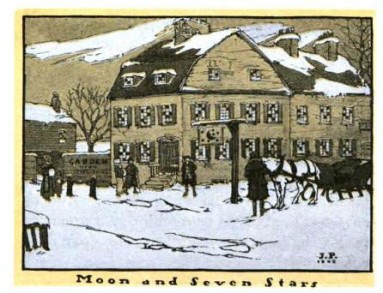

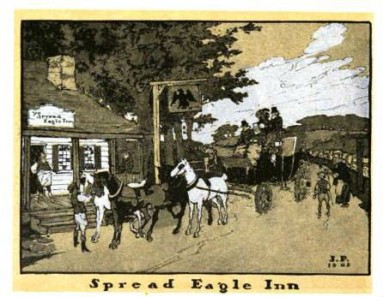

Illustrations from Inns and Ale Houses of Old Philadelphia (1909)

"This life at best is but an inn, and we the passengers." --James Howell

Verminous hotels, lackluster eateries, dubious rest stops: the open road has its perils. I remember a night I spent in Clovis, New Mexico. I took a room in a thirty-dollar motel during a cross-country drive. From the freeway its sign, a bright green clover superimposed on a royal flush, had beckoned me. The tiny room smelled the same as the town -- like cow flop. White-line hypnosis blinded me to the stains on its carpet, the holes in its walls. On a creaky twin bed I fell into black sleep. Not long after I awoke to tremendous itching. I flung back the covers. Fleas were biting me all over my body. I'd have no rest that night. After twenty minutes of fruitless pleading for a refund with an impassive front-desk clerk, I left at dawn, bleary, mottled, wishing for a bottle of calamine lotion.

Dr. Johnson also wrote: "As the Spanish proverb says, 'He who would bring home the wealth of the Indies must carry the wealth of the Indies with him,' so it is in travelling, -- a man must carry knowledge with him if he would bring home knowledge."

"There is nothing which has yet been contrived by man by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn," Samuel Johnson wrote. As my experience in the Clovis motel suggested to me, this likely owes less to any inherent felicity than to relative scarcity. Finding cheery accommodations is much like water dowsing or snipe hunting. In early America this was even more true. Though inns and taverns (the two were synonymous) outnumbered any other kind of business in colonial America, you had to be a lucky traveler indeed to avoid bedbugs, fleas, tainted cider, grifters, and drifters.

"Of all noxious animals, too, the most noxious is a tourist." --Reverend F. Kilvert

Foreign visitors often regretted their stays in American taverns. Irishman Isaac Weld found "filthy beds swarming with bugs" on his visit. Charles Dickens, staying in an inn outside of Pittsburgh, complained of linen "as yellow as the little rivulets" of tobacco that ran from seemingly every man's mouth and of tablecloths crawling with "a sort of game not on the bill of fare." Conditions deteriorated as one traveled south or west. This Margaret Hall discovered when journeying between Washington and New Orleans in 1828. Everywhere she went fleas plagued her. "We bring them along with us in our clothes," she wrote in her record of her travels, "and when I undress I find them crawling on my skin, nasty wretches."

"Always be in a bad humour when you are travelling," counsels James Kirke Paulding in The New Mirror for Travellers (1828). "Nothing is so vulgar as perpetual cheerfulness. It proves a person devoid of well bred sensibility."

Such discomfort appeared altogether ordinary. In New Orleans, Hall saw women delousing their children "according to the method depicted in an engraving of similar proceeding in the streets of Naples." In his 1832 travel account

Six Months in America, Englishman Godfrey Thomas Vigne reports that Cincinnati inns, though they served tasty fare, teemed with "the worst of vermin." So vicious did the nighttime assaults of Cincy's lice prove that they caused Vigne to dream of "the most unconnected subjects, -- bullfrogs, and universal suffrage, for instance."

That American inns often left much to be desired was not surprising. Many were frontier farmhouses, isolated and austere, offering guests little more than a pint of cider and a hay-stuffed pillow. This last comfort often had to be shared

A shared pillow, however, was the least of their worries. Adams had a cold, and Franklin liked chill, fresh air. Their entire stay they spent fighting over whether to open the room's lone window.

, as John Adams and Benjamin Franklin discovered one night in a New Brunswick, New Jersey inn.

The unsavoriness of many American taverns and inns belied the fact that, at least around the time of the Revolution, innkeepers and publicans could be numbered among the most revered members of a community. They hailed from the ranks of former deacons, assemblymen, town clerks, and justices of the peace.

The prestige and desirability of tavern and inn keeping declined as more and more licenses were granted to widows as a way to keep them off community welfare rolls.

Traveling through New York state, one British visitor remarked on the number of "lawyers, ex-judges, and former members of the legislature who kept tavern." Even those who once bore muskets didn't shy from the cider barrel. Innkeeping proved a popular occupation for Revolutionary War veterans seeking to restore fortunes lost during the hostilities.

These men of business and war bore a solemn responsibility. The necessity for long and frequent travel in early America made inns of paramount importance, and they were duly regulated. Almost all places that sold ale and cider had also to offer beds. A Maryland statute stipulated "six good and substantial beds, [with] sufficient warm covering for the same, and Rhode Island tasked all taverns with providing one bed for the "convenience of travelers."

"Travelling is the ruin of all happiness!" --Fanny Burney

New Jersey was perhaps the most exacting of all, requiring taverns not only "[to provide] an accommodation of strangers and travelers, the transaction of public business and the refreshment of mankind in a reasonable manner," but also to offer "sufficient accommodations for the stabling and pasturing of horses."

Though many inns earned their bad reputations, some of them did provide excellent service. Thomas Anbury, traveling through the United States in the 1780s, noted that the inns he stayed at were "equal to most in England," featuring "commodious rooms," tasty provisions, and attentive servants.

It was at The American Coffee House that James Otis, the Patriot best known for the catchphrase "Taxation without representation is tyranny," was attacked and driven insane by a party of British officers.

The Three Crowns in Philadelphia, kept by one Mistress Jones at Second street and Walnut, was known for its excellent food. There governors enjoyed ale flips made with gin, eggs and sugar. Boston also boasted fine accommodations: The Bunch of Grapes, The American Coffee House, Cromwell's Head and The Hancock House were all places of estimable public repose. And some inns went so far as to provide thrilling amusements, offering guests entertainment in the form of boxing matches and cock fights

Wrestling matches were another popular entertainment. Early Americans gave the sport a twist. Matches were concluded when, as Isaac Weld observed, "the wretches in their combat endeavor to their utmost to tear out each other's testicles."

. Journeying through Virginia in 1781, the Marquis de Chastellux stopped at a lonely wood-side inn, where he found one such fowl contest about to begin. The sight of "cocks with long steel spurs" failed to amuse him, and he admitted he could not say which astonished him more, the "insipidity of such diversion or the stupid interest with which it animates the parties." That this particular inn offered only a blanket and a spot on the taproom floor for sleep likely contributed to the visiting Frenchman's disdain.

Recipe for The Three Crowns's ale flip from Inns and Ale Houses of Old Philadelphia (1909): "Into two Quarts of old Ale (Friend Smith's Philadelphia brew hath the right Burton smack) pour a half pint of Gin. Beat four eggs well together with four ounces of sifted sugar. Stir in little by little the Ale and Gin. Then froth by pouring from jug to jug and serve in thin glasses, with fresh grated Nutmeg on top."

My most recent cross-country trip is now two weeks behind me, and I must admit I did not suffer any mishaps. Yet every time I hit the road I'm reminded that though much has changed since the days of the early Republic, much has still stayed the same. I can't help but think of a remark made by René Descartes. He said that traveling is much like talking with those of other centuries. If only they could warn you which present-day motels hide fleas.