Part One precedes this post.

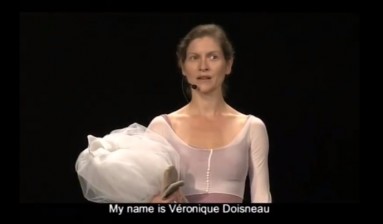

How mesmerizing could a choreography based on ballet and spoken word be? Very. I find it difficult to approach Véronique Doisneau (Jérôme Bel and Pierre Dupouey, 2004) with anything short of endearment.

The Paris Opera Ballet commissioned a documentary about Doisneau from Bel, a "low-rank" dancer a week away from retiring after a 20-year career. The evening of her last performance makes up Veronique Doisneau. Doisneau delivers a monologue like Zidane, but through direct oral address. Physically she is featured front-and-center onstage, not unlike a TED talk speaker, only gripping. She reveals that her career was marred by a back surgery at the age of 20, and works up to more revelations in a soft but resilient tone.

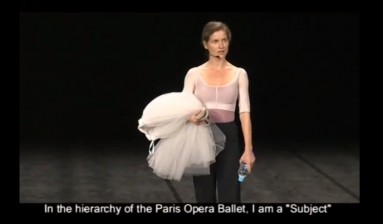

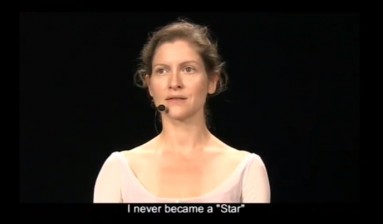

Doisneau never rose to the ranks of full étoiles or principal ballerina but remained a sujet, a performer who dances as a permanent fixture of the corps de ballet, often as a background dancer to the soloist. Her measured cadence and whispery tenor belie rarely spoken, even taboo, disclosures: she divulges her monthly salary, as well as her belief that she may not have been talented or physically strong enough to become a principal soloist. Like the inscrutable-turned-expressive Zidane in Gordon's film, Doisneau breaks the performer's fourth wall through monologue. Direct address places her in a spare but engrossing economy of language.

A full 85 seconds (6:15-7:40) of pacing, heavy breathing, doubling over knees, and rehydration to regain her composure (much like a professional athlete). An unaccustomed scene, watching a stage performer caught in the breaks of her act. As Ramsay Burt enumerates in "Revisiting 'No to Spectacle': Self Unfinished and Véronique Doisneau,": "One could tell from a strain in her voice which movements were the most demanding, and one could hear her becoming increasingly out of breath as the extract progressed. At the end, she took her time to get her breath back, sipping water, her heavy breathing broadcast throughout the auditorium. Her exhaustion was perhaps surprising. Not only had the stately quality of the material she performed not seemed especially strenuous, but ballet dancers conventionally strive to create an illusion of effortlessness."

Doisneau's physical exhaustion—her abrupt break from the airy perfection of ballet to the lethargy of a grounded earthling—is mesmerizing. (Here I must disagree with Burt when he writes that "watching her get her breath back was boring.") I was made uncomfortable not by my own inactivity, contrasted against Doisneau's actual breathlessness, but by the pleasure induced by watching such exertion. An guarded stage secret is set free. It's literally mortifying watching gods humbled to mere mortals.

Pleasure is a funny and flawed concept, and Bel x Doisneau interpolate all its ambiguous parts: the pleasure of making art (a "calling"), the pleasure of pain, and reciprocally, the spectator's pleasure in watching a working performer deconstruct their work.

Doisneau declares herself a spectator and great admirer of fellow ballerinas. In a memorable segment she invites Céline Talon on stage to dance Mats Ek's Giselle as Doisneau herself watches in a clever mise en abyme. (I had to look up both the name of the dancer and the piece; despite her protestations, Doisneau remains a riveting étoile here.)

Of being one of 32 dancers to perform immobilizing poses in Swan Lake: "We become a human decor to highlight the 'Stars.' And for us, it is the most horrible thing we do. Me, for example. I want to scream, or even leave the stage." Stripped of her 31 colleagues onstage, the previously wrenching and frenetic act Doisneau performed collectively hushes down to a frozen, staccato-like solo.

Both Gordon x Zidane and Bel x Doisneau rustle up a documentary form without being conceptually bound to the label at all (Bel calls his a "theatrical documentary"). What joins the works together is the dismantling of spectacle at the same time that we are caught almost helpless before it. Through the raw materials of performed labor—sweat, breath, technical skill—they furnish a rare space to visualize labor typically hidden from view through atomization, cheapened human life, and the technical flawlessness of spectacle.