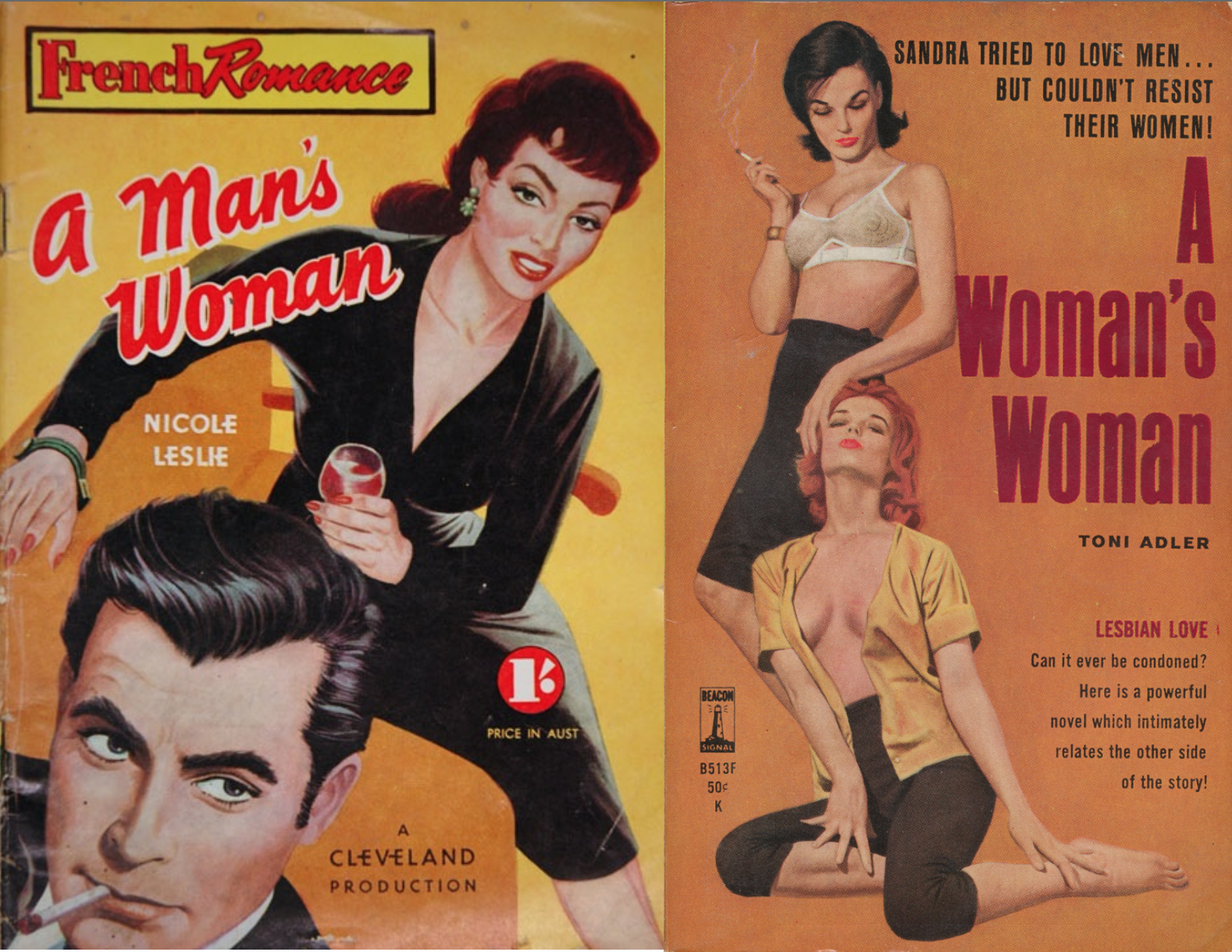

These women look suspiciously alike, eh?

Some years ago, my then-boyfriend said that Drew Barrymore was the ultimate “woman’s woman.” His reasoning: She stars in romantic comedies (née “chick flicks”), she seems like she might be vaguely feministy/ish (because of Charlie’s Angels, I guess?), she has her own cosmetics line, and her production company is named Flower Films, for crying out loud. Most of all, he claimed, “no men like her.”

Now, I was willing to buy most of this, even though it was clear that by “no men like her” he simply meant he didn’t like her: A chronicle of one rando dude’s quest to go on a date with Drew Barrymore became a successful documentary, she was perpetually on those “Hottest Celebrities” lists from various men’s websites until she “aged out” by hitting thirtyish. But I understood the larger point. Drew catered to women in her work, and she didn’t seem to need to cater to men. She could be pretty and charming and normal-ish and not particularly worry about being sexy—partly because she is sexy, but mostly because she’d already tried on the vixen persona in her earlier years and found it wanting (Poison Ivy, anyone?). So, sure, she’s a woman’s woman.

I recalled this exchange years later, when talking with a friend about what exactly the term “man’s woman” meant. I defined it as a woman who had an undeniable sex appeal regardless of her physical beauty, but I’d recently heard it defined as a woman who impresses men by eating the whole cheeseburger basket while appearing to stay effortlessly thin (and, presumably, hot). This friend then defined it as someone who seemed likeable enough and attractive enough that pretty much any straight guy on the planet would be happy to take her out, without being intimidated by her. As an example of the prototypical "man's woman" she chose—you guessed it—Drew Barrymore.

There’s plenty more to be said about Barrymore, but let’s give the poor lass a rest, and instead look at the larger question here: What is a “man’s woman”? What is a “woman’s woman”? We hear these terms being thrown around, and perhaps we’ve used them ourselves, but what do they mean?

I started poking around for the historical uses of these terms, and it turns out I’m hardly the first to seek out their precise definitions. “There are certain questions... [that] reappear at more or less irregular intervals, like comets, to throw the challenging gauntlet at the feet of every thinker not totally devoid of intelligence,” wrote an anonymous editor in an 1891 volume of Current Literature. “Of these queries none are more persistent and aggressive than that which concerns the difference between a ‘man’s woman’ and a ‘woman’s woman,’ and none have, from the woman’s point of view, been more weakly or illogically argued.” Even in those ’90s, the question was a stumper.

According to that editorial—which is a thoroughly fascinating and remarkably relevant read—the “man’s woman” is a naturally charming woman who is “interested intelligently and sincerely in the things dear to the heart of man,” though she mustn’t be too knowledgeable about those things, lest she outshine him. The “woman’s woman” comes in two breeds: the “sympathetic” type, who, with her knowledge of needlework and social niceties, seems a mix of Martha Stewart and Jacqueline Kennedy, and the “strong” type—the “poet, thinker, leader, reformer” that inspires women and girls to go beyond the domestic sphere. Poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning was listed as the classic example in 1891; today it would probably be someone more like Gloria Steinem or, hell, Lady Gaga.

So we’ve got the “man’s woman” and two types of “woman’s woman,” loosely defined as the Cool Girl, the Good Wife, and the Badass. But indeed, like a comet, the question keeps coming back, and over the past 120 years plenty have given it a stab. Over the years, curious readers have learned that the “man’s woman” may be spotted by her candor and fondness for playing rough in friendships—or she may be spotted not because men like her all that much, but because women don’t like her at all. Or maybe you identify her by the way she sits “listlessly” among other women, but when a man comes along, she’s suddenly able to “brighten up and in a moment become brilliant and beautiful.” Maybe you know her because she’s Melanie Griffith, or Debra Winger, or Keith Richards’ girlfriend. Perhaps you recognize her because she quietly marries and doesn’t cause her husband any trouble—or because she’s a wretched wife who makes her husband miserable.

As for the “woman’s woman”? She is docile, inconsequential, perhaps meek—or she’s a bigger threat to the patriarchy than a man’s woman could ever be. She has unique skills in the workplace—hire a “woman’s woman” on your sales team and you have insight into the heart of all women; put her on television and you’ve got yourself a successful talk-show hostess.

Ah, but then! What of the woman who is defined by falling outside these (handily ambiguous) parameters? Eva Peron was neither a man's woman nor a woman's woman; Julie Christie is both; Nicole Kidman is both—well, unless you ask Nicole herself (she thinks she’s a woman’s woman). And wait—if People magazine says that Debra Winger was the man’s woman of the 1970s, then why was the high-profile documentary about the paucity of women’s onscreen roles titled Searching for Debra Winger? Could Winger be both too?

Actually, there’s nothing extraordinary about Winger in this regard, just as there’s nothing extraordinary here about Drew Barrymore, or Nicole Kidman, or Eva Peron, or any of the women who can’t be easily pigeonholed into one category or the other. In truth, neither the “man’s woman” nor the “woman’s woman” exists. But the fact that we keep coming back to these terms despite never quite agreeing on what a “man’s woman” or a “woman’s woman” is reveals that collectively, we want them to exist, or at least we want the types to exist. Not just because we like to talk genderstuffs, but because we like to talk about women: Pit the “man’s woman” against her counterpart—the ladies’ man—and she becomes even more amorphous. We know exactly what a “ladies’ man” or a “man’s man” are, even when the particulars of their guises vary. Maybe it’s harder to pin down women’s women because women are supposedly so, you know, complicated.

But we can’t pin down the “woman’s woman” or her sister, because a formal classification of the two would end the conversation—and maybe that’s the top reason that we keep coming back to the question. After all, whenever the moniker is used, it says less about the woman in question, and more about the speaker (and we never tire of saying things about ourselves). And again, this isn’t a new thought: “As a matter of fact, the expressions...will nearly always be found to be based upon the contempt that one sex has for the judgment and powers of discrimination of the other…”—this from another journal printed in the 1890s. For a woman to call another of her kind a “woman’s woman” indicates an elevation of sorts, not only of the woman but of womankind—a “woman’s woman” is the prime example of her species, and what on earth would men know about women anyway?

Maybe we learn the most about the “man’s woman” and the “woman’s woman” when we look at the only thing that each of the varying definitions of the terms has in common: a belief that there’s something men want, and something women want—and ne’er the twain shall meet. It’s uncomfortable from a gender-binary perspective, naturally. But it’s just as uncomfortable from where I’m sitting, as someone who firmly identifies as female and who has plenty of traits associated with femininity. For whenever I’ve tried to puzzle out which camp I might belong in, neither one has felt satisfying. The “man’s woman” and the “woman’s woman” are each reactors, not actors in and of themselves. Each of these women fills the needs of others, even the heroic sort of “woman’s woman” who inspires other women—she’s still cast in the terms of others’ needs, not her own.

That’s how humanity works—we all react to one another, we’re social creatures—so in some ways it’s not all that problematic. But the fact that we’ve come up with dozens of ways to figure out how women might fill the needs of others by being a “man’s woman” or a “woman’s woman” says that we’re still more willing to cast women in supporting roles, not leads. That’s changing every day, of course. Now let’s let the “man’s woman” and the “woman’s woman” be part of that change by disappearing.