Rodrigo Hasbún’s Affections is a very short novel, the story of an ex-Nazi and his family trying to lose themselves in Bolivia. But because it repeatedly refuses to become the book you expect it to be—and because it lives in this moment of refusal, and never stops being a novel that refuses to be the novel you think it will be—that brevity makes it a lot easier to give it the re-reading that it both needs and deserves. I say that, because this is a novel that doesn’t end when it finishes: I started re-reading the early sections before I’d even finished the novel, and I strongly recommend this way of approaching its twelve interconnected vignettes. The novel’s short chapters feel more like paintings than prose: rather than read them end-to-end as a singular interconnected narrative, you watch them like the sort of movie that you rewind and freeze-frame. Or perhaps like a movie divided up into youtube clips.

I first got lost in this book because of the gentle complexity of Hasbún’s writing (which Sophie Hughes has outdone herself in translating); his sentences are clear and simple and direct, but they have a way of turning over on themselves, of changing into something else even while you are still reading them. Like his characters, the writing tends to be suspended between multiple timelines and perspectives, layered, overlapping, and emulsive; a recollection of the past will turn into an anticipation of the future and a psychologically revealing detail will suddenly turn out to be seen from and filtered through the perspective someone else.

Anyway, I have rarely read a novel so gently and quietly concerned with adding two and two and getting five, in fact, of making it possible to read the same sentence twice and see two different things. At first, I thought this was just because Hasbún is a very good writer—which he is—but it isn’t just that: to tell a story about a person is to freeze them in place, but to live the story that is told about you, to move forward in time from the image into which you were frozen, like a word being italicized—it does something to render that story a mere fiction, false and inadequate. And if telling stories is a form of control over reality—which it is—then living in a world made by stories is all about finding the places where the story doesn’t fit, where the lives we are sentenced to break apart and become something else. This novel is about that: Affections is not a story about lives, in the end; it’s about how people live in a world constructed by stories, how they make those stories, and how they are lost in them.

Let me confess: I am overthinking this novel. I am putting things into it that aren’t necessarily there on the page, grasping for a theoretical frame that would connect the dots in a novel that leaves these dots defiantly disconnected. But it’s the sort of novel that forces you to do that: by declining to tell a complete story—and by refusing to settle into a secure and stable narrative form—it leaves the reader with nothing to do but prowl around in the margins of the story, reading into the gaps that are left by the stories left untold and extending outwards into the stories that begin, are suggested, but the dots left unconnected. This is what happens when stories end, but time goes on.

Hasbún began writing this novel, as he recently told Scott Esposito, when he heard the story of Hans Ertl, from a friend, over beers; the friend had been writing the biography of Klaus Barbie—a Gestapo torturer who secretly lived in Bolivia for decades, before being extradited in 1983—and Hasbún had been fantasizing about writing a novel in which Barbie would be a character. You don’t have to ask why one would write a novel about such a person; a Nazi torturer, living in secret in the Americas… the story writes itself, comes alive, takes over. So much so, in fact, that many reviews of Affections refer to the novel that they had expected it to be, when they first heard a rough description: The Financial Times observes that “another writer might have exploited [this theme] more wordily,” for example, and The Scotsman can’t help but notice that “the easy option, which someone less talented and original might have taken, would have been to write a political thriller.” “A less daring writer would surely produce a doorstop of a family saga,” observes The National. And so on; a frequent refrain in the reviews is the sense that “another writer might have exploited [the material] more wordily,” that writing more would have filled in the “overall interconnectedness” of the material, which Hasbún has left “teasingly unresolved."

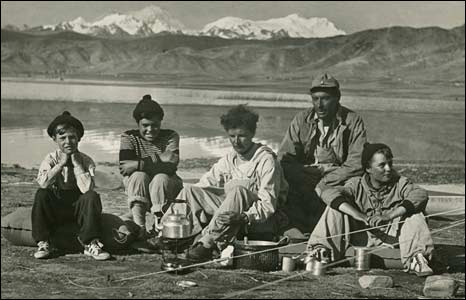

In these reviews, we find some of the stories that are present in Affections, some of the novels it doesn’t become. It could have been a political thriller or a family saga, a genre piece or a “doorstop”; it almost should have been, since we feel the subtle force of those stories in the interpretive pressure they exert on the novel. But Hasbún didn’t write those novels, because he didn’t write about Klaus Barbie. Instead, he was drawn to the much more enigmatic figure of Hans Ertl, a similar figure whose life is harder to summarize, if only because it kept going on. Barbie’s story is a three-act play, a gestapo torturer who fled and was caught. Done. But while Ertle’s life has some parallels with Barbie’s, those differences are key. Ertle had been Leni Riefenstahl’s cameraman for the 1936 Olympics, and had helped to film Rommel’s North African campaign, and—like Barbie, with whom he was friends—he took the “La Ruta de la Ratas” from Germany to the Americas, settling into semi-anonymity after the war to escape the disgrace of his Nazi past. But unlike Barbie, he was blacklisted after the war for his associations, not his actions; he was never brought to justice, because he was not a war criminal. As his surviving daughter recently insisted, he had been conscripted; in his defense, he did what he had to do to survive but never actually joined the Nazi party. Because the central drama of his greatest work of Nazi cinematography—Riefenstahl’s Olympiad—is really Jessie Owens’ triumph, not Hitler’s, you could even plead his case by saying that if Riefenstahl scripted the pageantry, he filmed the athletes.

In other words, he’s the sort of person for whom the phrase “Good German” was coined to gloss over the sins of willed ignorance and comfortable complicity and to exonerate the individual on the strength of their passivity. This is Ertl’s position, as we meet him in the early pages of the novel, railing against his disgrace, against the stories which have been told about him. His narcissism is such that he believes that he can be remembered as the first cameraman who filmed underwater, that his personal achievements in the cinema can and should be disentangled from his associations with Nazi Germany. The stories that are told about him are the wrong stories, he declares, and so he sets out to correct the record, to live a life in the new world that will leave his life in the old behind.

Since the novel begins with Ertl and his family embarking on a journey to find a lost Incan city—the lost and legendary Paititi, which Ertl believes to be the Bolivian Machu Pichu, and for which he plans to play the role of pioneering explorer—the reader can be forgiven for expecting that the novel will tell the story of the expedition, that we will read the drama of an old world exile struggling to transplant his family and his legacy in the new. But it doesn’t become this novel either; in fact, as it turns out, the novel will barely be about Ertl at all. The journey has hardly gotten underway when the narration leaps ahead, to the daughter and mother that were left behind—to the story, essentially, of a single cigarette they shared and what it means and will mean—and then it leaps again, and repeatedly, across the years that span the lives that each daughter will live afterwards. Affections will not, it turns out, be about Nazis in the Americas; it will be about what it feels like to feel affectionate to those who are, what it means to be the daughter of someone you might tendentiously argue to be a “Good German.”

It’s worth observing, at this point, just how many different novels this novel head-fakes then refuses to be, how many classics of Latin American literature one feels it to be associated with. I found the opening page reminiscent of the famous opening sentence of One Hundred Years of Solitude—with Ertl, as grandiose and narcissistic patriarch, a Quixote akin to José Arcadio Buendía himself—but since it concerns Nazis in the Americas, comparisons with Bolaño are unavoidable, and warranted. Moreover, Hasbún was the late Ricardo Piglia’s student at Princeton, where he wrote a dissertation about personal diaries, and it’s hard not to read this novel in the shadow of Piglio’s own literary diary, the first volume of which will be released in October; Affections is written in an intimate and personal voice, diaristic in feel, if not in fact. Moreover, since the Ertl family was real—and you can read their Wikipedia pages, if you want—the novel’s blurring of fact and fiction makes resemble any number of works that re-write the historical archive, especially in its desire to take stories framed by patriarchs and find the voices lost within them, of women. But the book never becomes Rodolpho Walsh or Diamala Eltit, either, or anyone else.

Any attempt to say what this novel is—the family saga as allegory for the nation, e.g., or an exploration of mid-century revolutionary violence in Latin America—swiftly becomes a statement of what the novel feels itself becoming and declines to be. And this, it seems to me, is what this novel is, this gesture of uneasy refusal and slippery deferral, the experience of a story being told just long enough for it to outgrow itself. But starting from the original flight from the family’s Nazi past—in which they are very literally displaced, and in the process of becoming something else—displacement comes to be more than just a theme. It is the novel’s mode of perception. Each of the twelve brief chapters has the narrative texture of a person looking at a photograph, and remembering or dreaming: As Hans Ertl and his family struggle to distance themselves from the images that he produced—and to make new ones for themselves—photography serves as a metaphor for the alienation of change. To take a photo of a thing is to make a record of the thing that it will never again be, the still point receding into the horizon behind you; to take a selfie, even, is to memorialize the person you’ll never again be.

I could describe what happens in the novel, I suppose, the dramas and lives its characters play out. But most of what “happens” in it happens off-screen, and most of the novel is scenes of anticipation, or memory, or even reveries about what could be, or could have been. Love affairs, killings, deaths and life… all the big events in the novel are experienced in memory or in anticipation. The result is that Affections is always one thing in the process of becoming another, but it never quite arrives; the future keeps receding and the past keeps piling up, ever present. Because we are always reading about just after or just before, life, in this novel, is what happens in-between, in the stories that are made to contain an uncontainable life and in the work of making new stories to contain what has not yet come. The reader is left suspended, shuttling back and forth along the timeline, looking forward and back for answers that never quite come. References to things that have already happened are rarely explained, or filled out; every time the novel seems to move in one direction, it shifts and sets off in another. As a result, every chapter feels like an excerpt from a much longer novel that we won’t get to read; every shot a reminder of all the angles and perspectives and footage left on the cutting room floor.

Scott Esposito called Affections “one of those brief novels that Latin America specializes in,” and these comparisons with “Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Horacio Castellanos Moya, Alejandro Zambra, and Samanta Schweblin” are certainly a good place to start. But Affections’ brevity—or, rather, its radical incompletion—is also very particularly its own: to remind you that while stories and photographs struggle to freeze time into manageable units, into usable pasts, time marches on. Because it’s incredibly important that we never even get an ending to the story; this is a novel that ends with the digging of a grave, but who will occupy that grave? The novel ends, but the grave still waits. Resting places are not this novel’s specialty, it turns out; time marches on and the camera keeps running.