Does the modern workplace cafeteria owe its existence one 19th-century activist's effort to feed the laboring multitudes?

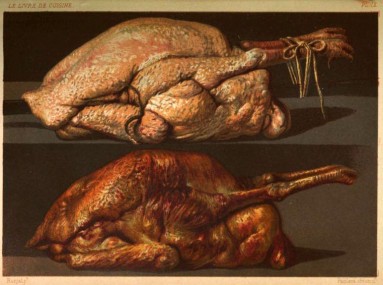

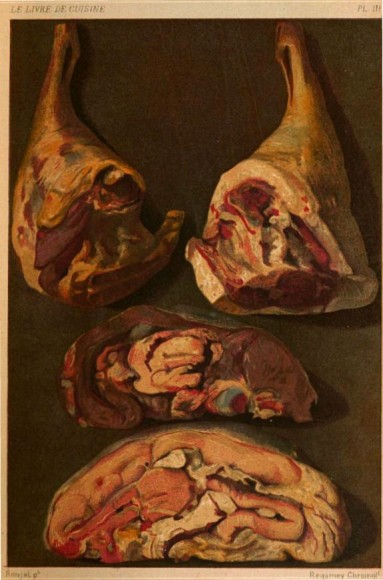

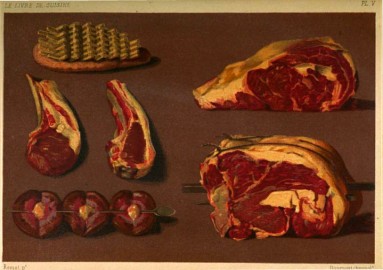

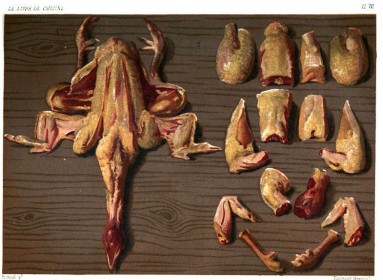

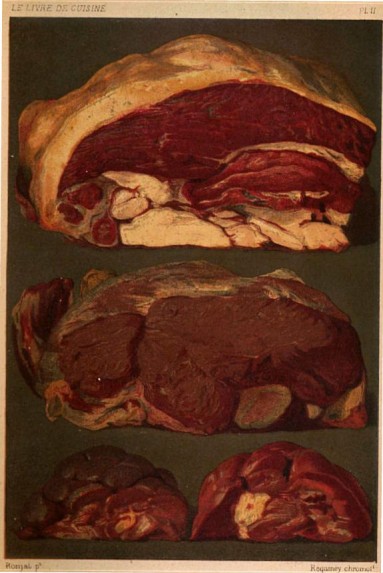

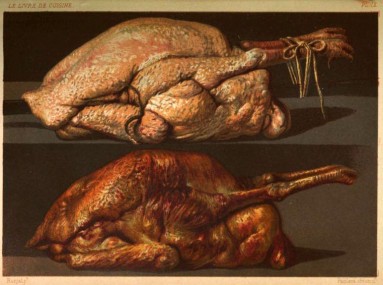

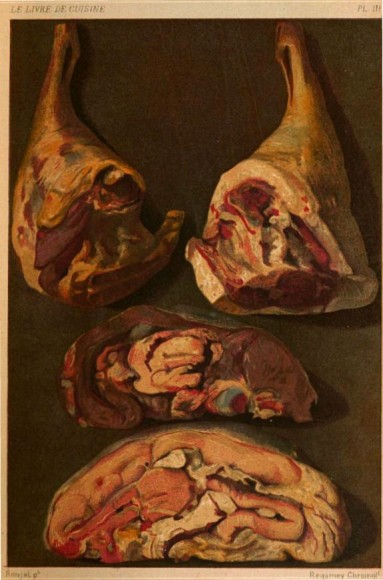

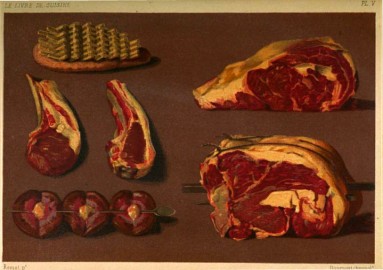

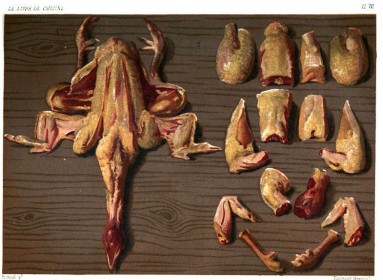

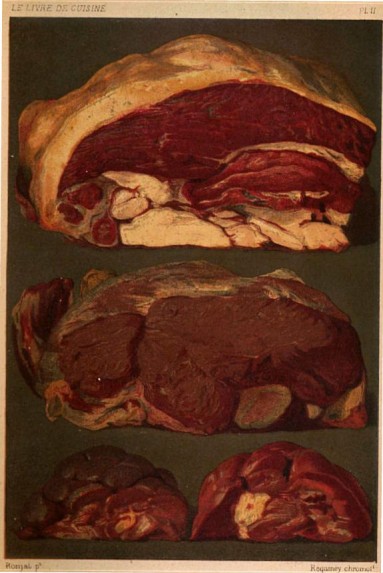

Illustrations from Le Livre de Cuisine (1867)

Though the phonograph and the funicular railway were the two marquee attractions of the 1897 World's Fair in Stockholm, Sweden, crowds flocked to another marvel that had garnered its share of buzz. Stockholm's famous People's Kitchen, which happened to occupy a space in the vicinity of the exhibition, served bowls of hearty soup, slabs of beef, pork and fish, plates of steaming vegetables, slices of rye bread, and mugs of weak beer known as iskällardricka.

The Stockholm kitchen was a pet project of Sweden's Prince Karl.

To partake of this smorgasbord cost a mere 40

øre (the equivalent of less than $1 U.S. today), a price that famished fair-goers found every bit as astonishing as the recorded human voice or alpine transport.

This prandial prodigy was not unique to Stockholm. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, People's Kitchens were as common in some cities as cafes and restaurants. In Berlin had opened the first, brainchild of Lina Morgenstern, the earnest, dreamy daughter of a wealthy Berlin family. Morgenstern’s father, a manager of the Royal Porcelain Factory's Breslau branch, sympathized with the 1848 revolution, and his leanings led him to make the comfort and well-being of his employees a main concern.

Morgenstern was also an ardent admirer of Friedrich Fröbel, who posited that the future of humankind lay in the hands of women, since theirs was the major formative influence during the first six years of a child's life.

The germ of paternal example took root in the daughter. Morgenstern likewise wished to do her part for working men and women. In 1868 she founded the Berlin Association of People's Kitchens, an organization whose mission it was to provide cheap, nourishing meals for the thousands thrown out of work by the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War two years before. To equip and maintain the kitchens she recruited middle class women, and to fund press coverage of the project she enlisted help from sponsors and donors. The endeavor met with success: The inaugural year's end saw the opening of not one but ten People's Kitchens, some of which served as many as 2,500 customers a day.

“The greatest dishes are very simple.” -- Auguste Escoffier

The philosophy behind the People's Kitchen rested on the conviction that the well-being of humanity depends on satisfying three primal needs: food, clothing and shelter. Any of these needs going unmet meant moral sickness, and from this, sooner or later, criminality. The most important of the three, food gave a man energy required to secure the remaining two. It must be made abundantly available, therefore, and it must be prepared according to strict scientific and aesthetic principles. The ideal meal consisted of two food groups -- "blood and muscle formers" (eggs, meat, milk, cheese and beans) and "fat-forming and heat-giving foods" (starches and sugar) -- and supplied enough nourishment that poor men and women need eat but once a day. Only the most destitute received their meals free; the Association stipulated that diners should never be made to feel themselves objects of charity.

In the 1890s, when Germany engaged in extensive rearmament, Morgenstern promoted peace. She was a delegate to the International League for General Disarmament, French League for Peace and the German Peace Society, and she served as vice president of the Women's Alliance for Peace.

Morgenstern's project quickly caught the attention of more influential parties. Kaiser Wilhelm and his wife Augusta became dedicated supporters, donating large sums and soliciting gifts from others. The Empress Elisabeth of Austria imported the idea to her country.

In 1898 an anarchist stabbed the empress to death in Geneva, Switzerland.

Spacious, cheerful, featuring high airy windows and marble floors, the Kitchen she sponsored in Vienna attracted each day over ten thousand diners. Its popularity stoked her enthusiasm to the point that she, along with some aristocratic friends whose help she enlisted, would lend their physical exertions to the effort. Any given day a visitor to her People's Kitchen might witness wasp-waisted ladies ladling hearty goulash and

knödel, white aprons covering their elegant walking dresses.

People’s Kitchens in Berlin, meanwhile, drew the press to their doors. In 1883 a correspondent for The Sanitary Record, an English-language publication concerned with matters of diet and hygiene, visited a People's Kitchen at the Berlin Sanitary Exhibition. He found it "a bright, cheery, social 'cookshop,' free from the sights and smells which repel all but the very poor and needy from the mere cookshops of London and its suburbs." He delighted in its cheerful throng of students, working men and women, tramps, artists and others, all there for the "plenteous, wholesome, nutritious noonday meal," and treated himself to a "toothsome and satisfying" lunch of boiled beef and vegetarian Irish stew.

Between the opening of its first kitchen in 1868, and the correspondent's visit in 1882, the Berlin Association of People's Kitchens reportedly served over 28 million meals. By the century's end, similar ventures began to appear in the United States. Mrs. James A. Burden and Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt Jr. chose a district of New York City inhabited mostly by longshoremen and unskilled laborers as the site for a People's Kitchen that opened under their patronage in 1915. Like its Continental and Scandinavian counterparts, this American eatery served wholesome, filling fare at a reasonable price.

In 1905 a People's Kitchen opened in the Jewish Quarter of New York's East Side. It fed and comforted immigrants fleeing persecution in Russia, Romania and other European countries.

Yet the ideals informing the Kitchens of Berlin, Austria, Stockholm and elsewhere enjoyed only imperfect translation across the Atlantic. Industrialists' wives, Mmes. Burden and Vanderbilt showed themselves shrewd investors in their own right.

Recipe for Green Beans with Potatoes from Lina Morgenstern's Koch-Rezepte der Berliner Volksküchen (1883): "100 kg green beans, 75 kg potatoes, 1 kg salt, seasonings, 1 kg flour, herbs and onions for stock, pepper, one bunch parsley. Directions: Cut the ends from the beans, break them into 2 or 3 pieces, blanch them in boiling water, take them out, and fill the pot with stock and seasonings, put the beans in and boil until soft. Then take out the seasonings (bay leaf or bouquet garni) thicken the liquid with flour, season with pepper, and once it has cooked awhile with the potatoes, add the chopped parsley. Serve with beef or salted pork."

Wedding lofty ideals to a sober concern for the bottom line, their version of the People's Kitchen they presented as "a business experiment with the social purpose of selling at cost good hot food." They hoped "to inculcate wholesome food habits" in working men and women who, they feared, would otherwise frequent the nearby saloons offering free sandwiches with purchase of a dram.

The American experiment proved every bit as successful as the European. Thousands lined up for the New York People's Kitchen's three-cent pots of split pea soup and baked beans. Taking cues from the endeavor's outcome, local factory owners installed their own lunch facilities. There workers might nosh nourishing food provided them as inducement to step up productivity. In-house cafeterias present in so many workplaces today perhaps trace their roots to these commissaries patterned after Morgenstern's altruistic eateries. Served hot meals by their employers, employees serve their employers' bottom line.