Peeling back the layers of this humble vegetable's history reveals that, no matter how you slice it, there's power in spuds

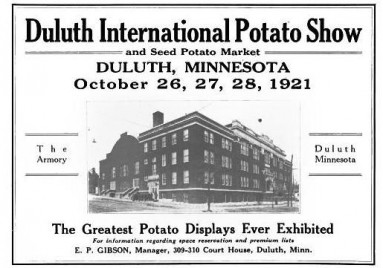

Illustrations from Potato Magazine (1920)

Nothing orients like food. Wherever I find myself living I try to eat according to the region and season. In Rhode Island I ate mussels and stuffed quahogs. Nopales, carnitas and citrus sustained me in Arizona. Pennsylvania presented me with a real cornucopia -- beets, cucumbers, duck eggs, garlic scapes, delicata squash, ground elk meat. Now that I’m in Maine, it’s potatoes for me.

Here you can buy them right off the truck. The parking lots of shopping centers you pass have occupying them potato-laden pickups minded by flinty, denimed Yankees or smartphone-fondling teens in halter tops and too much mascara. The potatoes typically come in two varieties: red and white. The reds are my favorite. I buy them five pounds at a time. They’re cheap

"I despise formal restaurants. I find all of that formality to be very base and vile. I would much rather eat potato chips on the sidewalk." --Werner Herzog

, and their earthy savor is such that you forget any threat to your pancreas or pants size. Plus, unlike that other, far more famous local food, they may be boiled without leaving you feeling as if you were some medieval inquisitor.

Potatoes have long caught the eye of folks with economy in their sights. Amelia Simmons ranked the potato first among vegetables for its “universal use, profit, and easy acquirement.” In her 1796 book American Cookery she counsels readers to turn spuds into pies, cakes, and puddings

To promote his favorite tuber in France, Benjamin Franklin advised French pharmacist Antoine Augustin Parmentier to hold a banquet featuring potatoes in every dish, including dessert.

. To those lacking the will or means for such flourishes she recommends simply boiling potatoes whole and eating them off the point of a knife. Sold on the virtues

Samuel Deane and Jared Eliot claimed the potato not only nourished the body, but enriched the land. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson appeared to have understood these virtues as well. Both founding fathers grew potatoes on their respective estates.

of this vegetable, which tasted passably good and stored well, practical-minded Americans took Simmons’s advice to heart. The most successful farmers of the young United States regularly sought advice on potato cultivation, and the perception reigned that he who could not afford to plant at least a bushel of potatoes was an unfortunate man, indeed.

Hardy and nutritious, the potato was a natural fit for the early American republic, whose citizens esteemed independence above all. Homesteaders and householders alike found that the food aided thrift and thus boosted their prosperity. A similar revelation occurred on the other side of the Atlantic, albeit in service to a different economic end. Under the influence of late 18th-century captains of then-infant British industry, Manchester and Liverpool became Britain’s two biggest markets for potatoes. Both cities daily received shipments of spuds carried on coal barges sent from nearby agricultural districts. With so much of such a cheap staple on hand, the reasoning went, there was little need to increase workers’ pay.

Laborers in rural centers suffered the same consequence their shipments visited on their urban, industrial counterparts. Spuds killed wages. Development of certain unjust economic arrangements thus followed in short order. The cottier system was one such arrangement. Under it, families rented a small cabin on an acre or two of land. On the land they grew potatoes and oats for both sale and sustenance. Leases on these holdings typically renewing yearly meant landlords found regular opportunity to put up rents, which they often demanded in the form of labor. The ever greater exactions they no doubt thought their tenants able to meet, thanks to the inexpensive, reliable food source in the potato on hand. British civil servant Sir Charles Trevelyan deplored the practice, observing that “relations of employer and employed, which knit together the framework of society, and establish mutual dependence and good-will, have no existence in the potato system.”

"Lo! the Irish landlord and absentee / In a drawing-room sits with company / At a mansion of pride in London Square ... They talk of ball, concert and Court; then to break / The reign of ennui, and of something to speak, / They cried, what accounts are from Ireland! -- dismaying! / It is all from potatoes so queerly decaying: / But this no one could help, nor the evil prevent, / And all hoped that their tenants would pay the rent." --from "The Feast of Famine: An Irish Banquet" (1846-7)

Abuses owing the prolific crop eventually prompted questioning and debate. By the 19th century’s end Britain’s well-to-do began to wonder whether potatoes didn’t create more problems than they solved. Yet at issue weren’t those abuses committed by wage-gouging industrialists or rack-renting landlords, but those perceived to originate with the wage-gouged and rent-racked. A food easily gotten was not soon given up

So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for for the time being. --Franz Kafka

. The fear grew that Britain’s lower classes might fall willing captives to a potato monoculture. Toil would ease, and with it discipline, breeding serious moral and social ills. The “effect of depending too exclusively on the culture of the Potato is fearfully exhibited in the Irish people,” wrote surgeon Alfred Smee. Among the casualties of spud-induced indolence he numbered “millions of paupers who live but are not clothed, who marry but do not work, [who care] for nothing but their dish of potatoes.”

The issue of dependence went from a pet concern of a wealthy few to a matter calling for government action. In 1845, the Devon Commission reported that potatoes "enabled a large family to live on food produced in great quantities at a trifling cost.” It went on to note with alarm that “as the result, the increase of the people has been gigantic.”

"The land in Ireland is infinitely more peopled than in England; and to give full effect to the natural resources of the country, a great part of the population should be swept from the soil." --From a letter from Thomas Malthus to David Ricardo, August 17, 1817

Whereas the Commission recommended that local authorities step up food production, the propertied classes for their part tabled a more extreme solution: eliminate the potato in order to eliminate the problem.

As it turned out, the problem reached something of an inflection point soon after the Devon Commission published its findings. A virulent blight struck Ireland’s potato fields. Some two million people died in the course of a year. Survivors fared little better. With no crops to sell, half a million of them found themselves homeless, wandering a countryside in which fields of dead potato plants were said to have smelled like rotting flesh. Those who could left for the United States, preferring to start anew in a strange country than starve at home.

If in a dream potatoes should appear, it's a sign of good fortune to come.

Unremitting misery inspired dark theories as to the blight’s cause.

"Fatten one with oats, peas, or barley, and another with potatoes, and attend to the difference of quality in the flesh. The flesh of the corn-fed hog will be of a good colour, firm, elastic, will swell in boiling, will prove of savoury flavour, and of the strongest nutritive power. The potato-fed flesh will be loose and flabby, of a dingy colour, of far less specific weight than the corn-fed; will shrink in boiling, have an insipid taste, and have far inferior effect in point of nutrition." --"Mr. Lawrence on the Difference of Starch" (1818)

Many blamed divine wrath, some even speculating about its justification and mechanism. Volcanic action, one writer’s surmised, heavenly powers set in motion to “cause government to improve the conditions of the lower classes, which ought to have been done long ago.” Another writer construed the blight as punishment visited on the poor for feasting on a food that really ought to go only to pigs. More scientifically informed opinions cited as the cause everything from strange weather to aphids.

Some suggested that the blight was transported on potatoes being carried to feed passengers on clipper ships sailing from America to Ireland.

"Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism are all very good words for the lips: especially prunes and prism. You will find it serviceable, in the formation of a demeanour, if you sometimes say to yourself in company -- on entering a room, for instance -- Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes and prism, prunes and prism.' --Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (1857)

Most everyone agreed that such great dependence on a single crop could only have led to disaster. The famine of 1845-1846 didn’t mark the first time the potato crop failed. Earlier blights certainly occurred with some regularity, but they had been more or less local. The 1845-1846 blight, however, belonged to an entirely new order of magnitude. It “literally shook Ireland to the very roots of her economic, social and political being,” writes historian Redcliffe N. Salaman, and led “[the] majority of people ... to realize the danger of building their social structure on so narrow and precarious a basis.”

Recipe for cold potatoes from Aunt Mary's New England Cook Book (1881): "If you have cold boiled potatoes on hand, put them into cold water and bring it to a boil; they will be heated through then and can be used for hash or fishballs, and are just as good is perfectly sweet."

It was a difficult lesson to learn. Yet it seems we have too quickly forgotten it. "Without the potato," writes Michael Pollan, "the balance of European power might never have tilted north." The unassuming tuber showed us just how briskly food and industrialism have been made to walk hand in glove. Yesterday it was the potato system. Today it's "King Corn." Either crop in its time has caused as much misery as prosperity. Whether we'll continue to turn a deaf ear to current dire predictions, or we'll turn our eyes to sensible solutions, only time will tell.