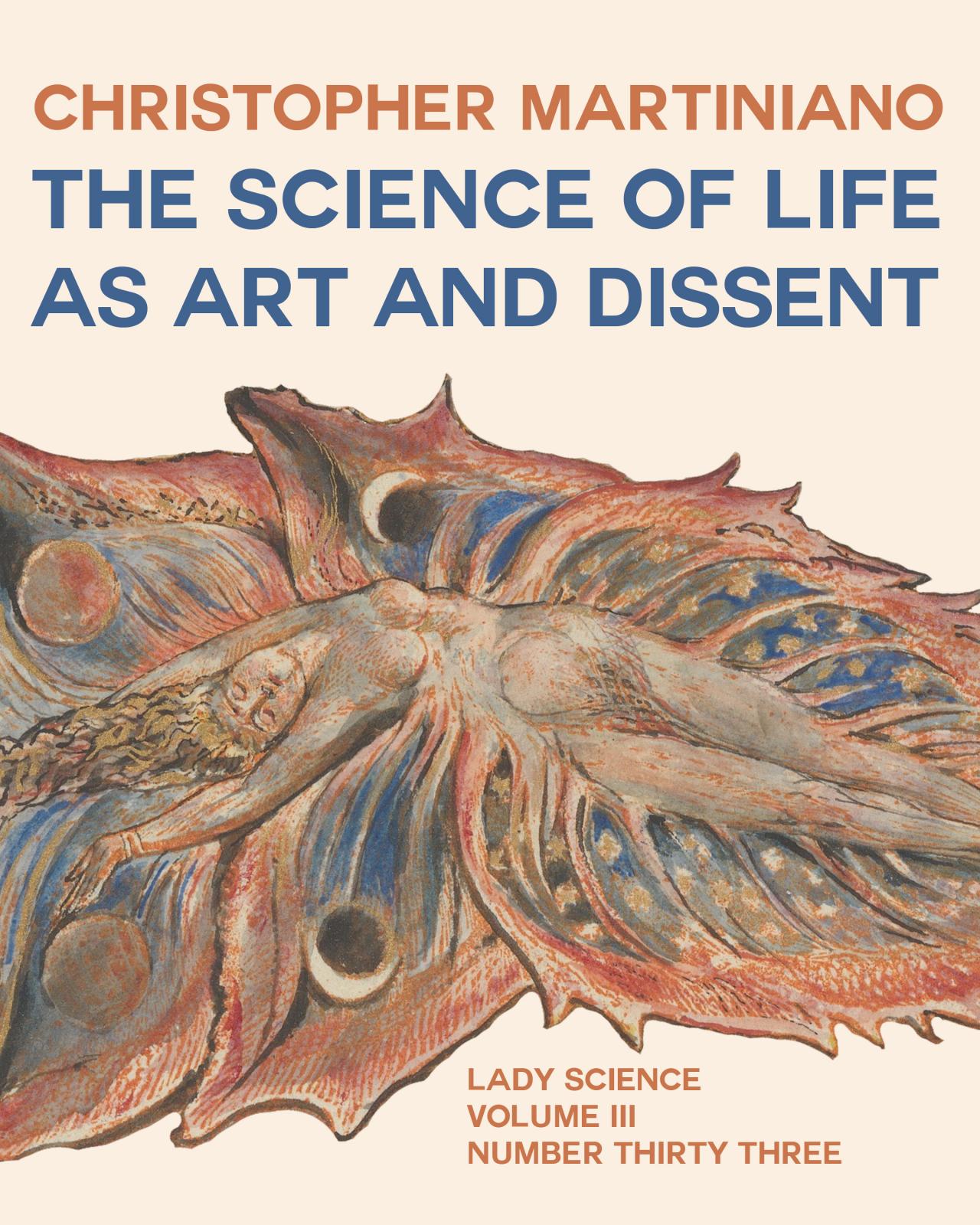

By Christopher Martiniano

“For some time now,” Friedrich Nietzsche opened Will To Power, “our whole European culture has been moving with a tortured tension that is growing.” Nietzsche worried that it had been moving “toward a catastrophe: relentlessly, violently, headlong, like a river that wants to reach the end, that no longer reflects, that is afraid to reflect.” But now, over 100 years later, the renewed mainstreaming of authoritarianism in the United States and populism across Europe demands that we reflect. In the 18th century, faced with the increasingly authoritarian actions of William Pitt’s government, William Blake’s Jerusalem offered a poetics of resistance inspired by contemporary science. In the poem, the disorderly forces of epigenesis and a willful, feminine nature subvert the strictly gendered, hierarchical thinking of the Enlightenment that animated Pitt’s government.

The London of the 1790s–the apex of the Enlightenment–is a history that is both far and near to 2017 America as it provides an analogue for resisting our own impending catastrophe. Inspired by new models of life developed in the biological sciences, 18th century Romantic artists like William Blake explored an alternative to the mechanistic, divisive Enlightenment principles that drove the oppressive legislation during the 1790s. As our river moves relentlessly toward catastrophe, it floods American homes, streets, and classrooms with a similar “tortured tension” that Nietzsche felt. As the tension floods 2017, resistance is necessary but so too is reflection.

Though not fascistic in our sense, England’s Prime Minister during the late 18th century William Pitt acted with an overwhelming authoritarianism that attempted to divide its populace with xenophobic mistrust and fear. England was financially reeling from the American Revolution, weary of the aftermath of the recent French Revolution, and anxious about a potential war with France. Pitt’s government was also fearful of an impending uprising in England and Ireland and wary of spies among its own, uneasy populace. Against these threats, Pitt’s government demanded order and prescribed sweeping legislation designed to effectively silence any potential for radicalization, reform, or protest.

In many ways, Pitt’s government was informed by Enlightenment principles, which sought to free intellectual culture from the tyranny of nature, superstition, and tradition—concepts inextricably tied to the feminine. These gendered, idealist conceptions of the Enlightenment encoded the destructive implications of its binary system of domination: the mastery of a masculine, progressive science over tradition and superstition, instrumental reason’s order over unruly emotion and intuition, rational mechanistic dominion over chaotic nature, and the autonomous self over community. The subjugated half of this binary became the “Other.” Eighteenth-century otherness forced women into “slavish obedience” according to Mary Wollstonecraft; it legitimized the slave trade; and it reached its logical peak with Auschwitz in the 20th century as Theodor Adorno and others argue. Simone de Beauvoir provocatively articulated otherness in terms of gender in The Second Sex: “He is the Subject, he is the Absolute–she is the Other.”

Pitt, like our own President, became the law and order Prime Minister during the 1790s. Historians often refer to his Ministry as Pitt’s “Reign of Alarm” and Mr. Pitt’s War to describe the “extreme social tension” and chilling of dissent that London felt during the 1790s. In 1794, Pitt suspended the writ of habeas corpus and enacted the Seditious Meetings Act of 1795, which restricted the right to public assembly. Common to authoritarian regimes, Pitt’s government privileged individuality and autonomy over solidarity and community, ultimately weakening the social fabric of London and its many dissenting voices. Similarly, the 1799 Combination Acts restricted the formation of reformer societies. In an effort to further dissolve community, Pitt’s government prescribed the “gagging acts” of 1795 that stifled public debate, publication, and protest under penalty of death.

To counter Pitt, English poet William Blake (1757-1827) challenged the Enlightenment thinking embedded in Pitt’s political philosophy and oppressive legislation. As a political and religious radical, Blake infamously undoes the Enlightenment’s mechanism of binary thinking, claiming that “[w]ithout contraries is no progression.” Blake believed in the necessity for opposites, not domination of one over the other. Although Blake scholars are often reticent to “let him off the hook” in regards to what Sarah Haggarty and Jon Mee call “the proliferation …of misogynistic images” in his work, his major illustrated poem, Jerusalem The Emanation of The Giant Albion (composed ca 1804-1820) imagines the principle of generation as the redeemer of the fallen, divided world that Blake found himself in at the turn of the 19th century.

In Jerusalem, Blake narrates the fall of the (Christian) world, personified through his mythology of Albion (Great Britain), and its ultimate restoration, unification, and redemption in a place of forgiveness: a woman named Jerusalem. Copiously illustrated, the 100 page poem is divided into 4 chapters, each addressed to a different reader: “To the Public,” “To the Jews,” “To the Deists,” and “To the Christians.” In the poem’s open, Jesus calls on Albion, the father of humankind, who turned away, hid, and fell into a “deadly sleep.” The remainder of the poem, the “dream-plot,” follows the fall of humankind into deadly sleep, humankind’s passage through Eternal Death, and, eventually, an awakening to Eternal Life illustrated on one of the poem’s final pages.

Jerusalem is inspired, in part, by the biological sciences of the 18th century. Denise Gigante’s cultural study of this era, Life: Organic Form and Romanticism argues that Jerusalem’s story of unification is shaped by the larger, scientific effort to find truth about living form found in the feminine principle of generation and vital power. The poem and its illustrations resist presenting sexual reproduction as a “matrix of…marriage, patriarchy, primogeniture, and other institutions that perpetuate gendered division and hierarchy.” Instead, Blake’s poem is inspired by the scientific study of “epigenesis,” which theorizes that vital power is internally motivated and sustained in an organism’s ability to self-generate. Eighteenth century scientists attempted to identify the powerful, creative life energy infused in all things. Gigante argues that epigenetic theories signaled a change in thinking about organic form structurally to understanding life in terms of “power” and “force.”

Jerusalem reveals a generative, vital quality in its length, sheer scope, density, its seeming formlessness proliferation of intermingling narrative lines, its many drawn figures that proliferate from one another, its many styles, and its many self-contained poems. However, those same features often frustrate and overwhelm readers of Blake’s “monstrous” poem, as it becomes a seemingly uncontrollable reproductive force. Such naturally occurring forces in the scientific world evoked fear of a nature that fought the containment of rationality and reason. Gigante reads Jerusalem as a manifestation of “epigenesist poetics,” an artistic analogue to a notion of nature pitted against an increasingly mechanistic worldview. Jerusalem’s vitality, its immensity and unwillingness to follow order in any traditional way, offers a poetic and visual form of resistance to the stifling, repressive, and stultifying calculability of the Enlightenment and Pitt’s War on London.

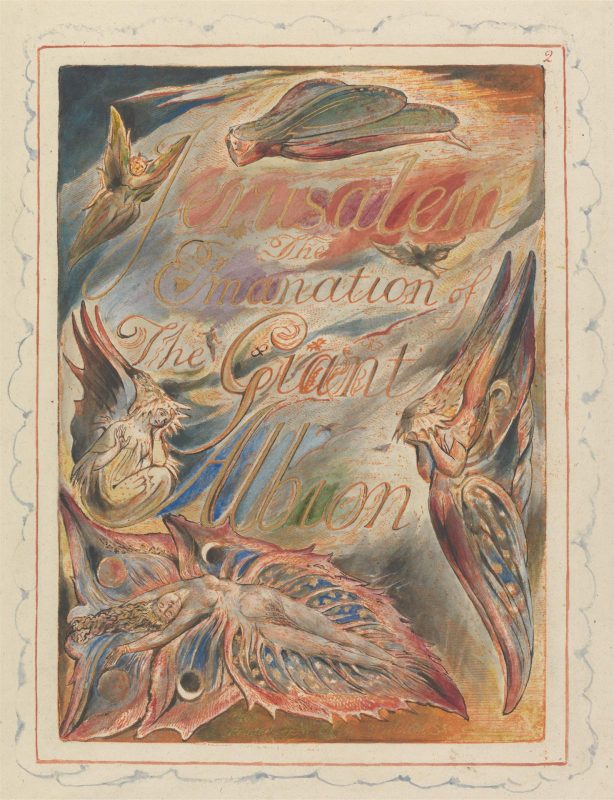

Offering an alternative to the Enlightenment thought that animated Pitt’s authoritarianism, Blake associates vital, generative power with biology and imagination in the very opening of the poem on its illustrated title page.

Plate 2. Relief etching print from Jerusalem, William Blake. (Published with permission from the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Five insect-like female figures crouch over vegetation in a wash of greens, yellows, reds, and umber. By situating plant, insect, and animal life in generative, symbiotic relationship in and amongst nature, Blake resists standard biological, hierarchical categories and mechanistic understanding of life. Against a mechanistic worldview, which claims living things and their parts lack any intrinsic relationship to each other, Blake shows how diverse forms of life are interrelated.

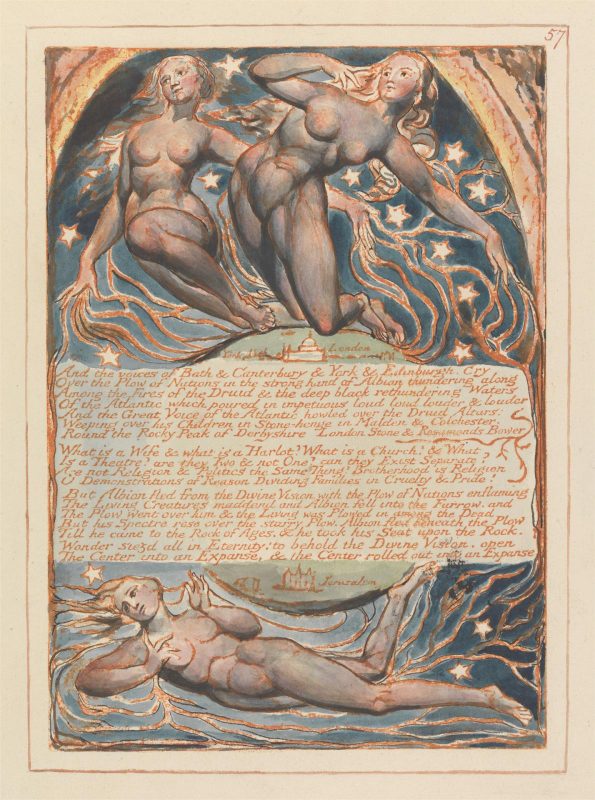

Blake shows three female figures undergoing further epigenetic self-generation, which reinforces the relationship of the feminine, natural world with vital power.

Plate 57. Relief etching print from Jerusalem, William Blake. (Published with permission from the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

The figure’s vegetative tendrils emanate from their hair and fingertips to surround the text block in the middle, which ends, “Wonder seized all in Eternity! To behold the Divine Vision.” These figures complement the text and Blake’s “Divine Vision” of a feminine epigenetic creation against the solitary male figure with his scroll, representative of the individualized rationality of Enlightenment thought.

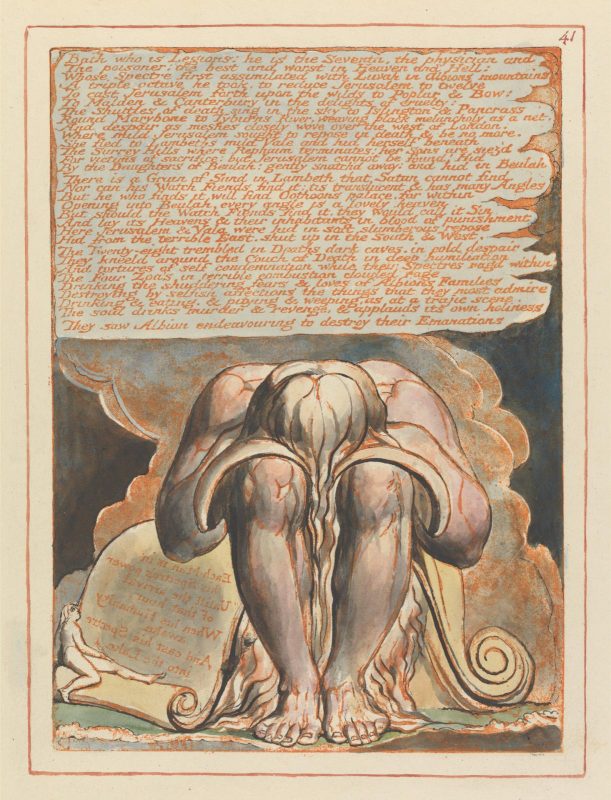

Plate 41. Relief etching print from Jerusalem, William Blake. (Published with permission from the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

As a poem, Jerusalem resists order, experimenting artistically with epigenetic concepts of generation, feminine nature, and freedom. Epigenesis, “the additament of parts budding one out of another,” resists the “atomistic disjointedness” and the Enlightenment’s alienating forces driving Pitt’s war. Though the five vegetative, insect-like figures on the title page appear in varying states of sorrow and “deadly sleep,” through the process of epigenesis, represented in both text and images, they awaken anew by the end of the poem. Blake produced an art inspired by a science that invigorates life, not enervates it, that unites not divides.

Chris is a PhD candidate in British Literature and Art History at the Indiana University/Bloomington. His research interests include eighteenth-century aesthetic theory/philosophy, poetry, art history, media, and music. Currently Chris teaches for the Department of English and School of Communication at Loyola University Chicago. Contact: [email protected]; http://theboundingline.com/.