Keah Brown's work first came to my attention with her nuanced critical view of disability and film in Catapult, and my appreciation of her work only deepened with "The Freedom of a Ponytail" , an essay about the triumph of learning to put her hair in a ponytail one-handed, as necessitated by the cerebral palsy that affects mobility on the right side of her body. In Lenny Letter, she writes: "[My ponytails] are a promise of more to come, a promise to keep working at them until they are the best that they can be. I find myself wondering back to that list of things I can't do and imagining a world in which I can. ... Being able to put my hair up didn't make me instantly love myself or my body, but it helped me see that I could one day." You can follow her on Twitter here, and visit her website here.

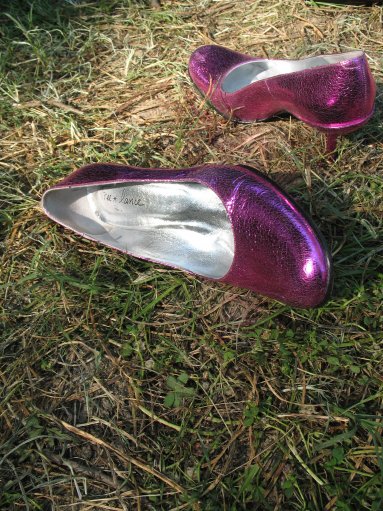

"And then I watched as their feet grew tired when the night went on and those same heels ended up in their hands or at the tables by their purses." (Photo: Tangi Bertin, Creative Commons license.)

One of the first times I ever felt beautiful was at my high school prom. I stood on the venue’s version of a dancefloor and thanked the classmates who passed by me and complimented my dress. My dress, to this day, is one of the prettiest things I have ever worn, a black and pink ball gown with corset ties and enough tulle to make your head spin. I looked like a princess and felt like one too, with the tiara to match. I believed them when they said I was beautiful. I had no reason not to. I knew that the dress fit my body and skin tone well. I felt at my prettiest then, even as I wore silver sparkly flats that I bought from Payless two nights before. I watched my classmates walk and dance in their sky-high heels with ease. And then I watched as their feet grew tired when the night went on and those same heels ended up in their hands or at the tables by their purses.

The trouble with prom is that it’s only one night, and that feeling of being beautiful ended when it did. However, the envy of the girls and their sky-high heels remained. Though I had plenty of reasons to be jealous of the girls themselves, I found myself specifically envious of their ability to walk in heels. High heels are beautiful. I say this as a person who has never been and will never be able to wear them. I don’t have the coordination and the balance to do so. I heard once that we often crave the things we can’t have. We wish for a scenario or a world in which the thing we can’t have, the thing we can’t do, is possible; we crave a bit of magic. I am and was no different. Growing up as a black disabled woman with cerebral palsy, I wished for many things. I wished for a new body entirely, asking only to wake up with the same black skin, same name, and the same family everything else could go. I wished for knees and feet that didn’t ache after walking through malls and on park trails, grocery stores and movie theaters. And around the time of each high school dance I wished for a magic pair of heels that were secretly made just for me to walk in. I wanted them to be a secret because I feared they wouldn’t work if other people knew about them. I’d like to think that they would appear on my doorstep in a black and white box with a note that read “Keah, here is the only beauty secret you need.” I likened them to The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants books. I was a huge fan at the time and thought that if they were allowed a pair of magic pants I should be allowed one pair of magic heels. The pair of enchanted heels never came for me but I still found myself admiring heels from afar, picking them up in stores and asking my mom and sister if they thought the heels on the shoes were small enough for me to walk in even when we all knew the answer was no.

There are lots of things I can’t do: cartwheels, backbends and walkovers, fly, wink, or whistle, blow bubbles, crack an egg or the code to the perfect Rubik’s cube, and this is not due to a lack of trying. In fact, I spent many of my adolescent years trying to do cartwheels and backbends at home and after cheer practices with my sister. I spent summers at park programs trying to whistle and blow the biggest bubble while in competition with the other kids. All of this was a result of fearlessness. When you’re younger, fear is a thing you know but not something you practice. Fear is the thing you tuck away in the furthest part of your mind while you do the things you love or dream without abandon. The lack of fear as a young girl is what kept me believing the impossible and continually trying the things that were genuinely impossible. We live in a society that touts the message “nothing is impossible if you believe hard enough!” but that’s simply untrue and quite frankly, harmful.

People with disabilities are regarded as worthy only when we “achieve” and “defy expectations”; we are led to believe that our worth lies in how closely we can align ourselves to the able-bodied, Eurocentric beauty standards that our society holds so dear. After all, high heels are sexy and fun; they make women irresistible and men drool, if you ask any advertisement, movie, TV show, or image eager to convey desirability. The “irresistible” women in these images are never in flats like I was at prom. They’re in heels as high as possible, walking confidently as the heels click-clack on their feet. They are models on the runways of the biggest fashion companies with heels bedazzled and strappy, a silent promise that a heel is the necessary shoe to complete whatever look graces their bodies. When the models aren’t in heels, their look is just as unattainable. They’re shown in t-shirt-and-jeans-and-I-just-woke-up-like-this beauty that is just as alienating. These women do not wear heels all the time but we are lead to believe that certain looks are incomplete without heels, often overlooking the ableist nature of such a message. The images presented to us are easy to buy into. When you are fed the narrative that almost every single body but yours is desirable, you believe it. So it’s easy to look at the images of those same beautiful women in high heels and back at yourself, and think, Maybe I’ll never be as desirable and sexy like those women. It’s not just that we share no similarities in body type, or often, race. It’s also that I can’t even indulge in the primary simulacrum of their sexiness. I can’t even wear their shoes.

When I was in college, my friends and I would sometimes leave campus and go to our Galleria Mall. I would pick out clothes I was almost always too lazy to try on and wait for my friends while they did the responsible thing and made sure their clothes fit before buying them. They would try on their clothes and we’d collectively agree or veto them, and I’d always wander back by the shoes, picking up and putting down heels that were far too thin and too tall for anyone but an expert to walk in. I would sit with the shoes for a bit while waiting for my friends to change and close my eyes and imagine a world where the shoe was both in my size ten foot and wearable. Under my closed lids my friends would ooh and ahh as the heels sculpted my feet like art before I’d take them off and bring them to the register for purchasing. These dreams would end once my name was called or one of my friends stepped out of the dressing room to ask me how the clothes looked, but I enjoyed each moment anyway.

High heels have always been one of the things I’ve loved but could never have. This realization came to me early. I am very familiar with my body’s limitations and I take great care to wear sneakers with heel and arch support when I am walking anywhere regardless of the distance. I often ask myself: How much of my inability to walk in heels is fear, and how much of it is the result of the body I am housed in? Fear, in a twisted way, brings me comfort. Fear is familiar and digestible in a way that the reality of not being able to wear heels is not. Fear allows me the room to lie to myself and say that fear is the only reason I cannot wear heels. When in reality, that’s not the case.

The answer doesn’t exactly matter in the grand scheme of things because the fact of the matter is that it’s just not something I’ll ever be able to do, despite the messages that nothing is impossible. However, when I posed the question of the ability to or to not wear heels on Twitter I was surprised by the response. Like many people, my circumstances, failures, and inability to do certain things have always felt like circumstances I’ve always dealt with alone. As ridiculous as it sounds, I’d already convinced myself that I was the only person in the world who could not wear heels and in turn, could not be desired by anyone. I found out a few weeks ago that this was not only ridiculous but untrue. The same balancing issues that I have, other folks with disabilities have as well. The same aching feet and need for stability is theirs as well, and they still found significant others. Despite the lack of heels in their lives they still love, and are loved. The femininity, desirability, and embrace of womanhood that I feared I did not deserve without the ability to adhere to the standards set and reinforced by society, I’ve had all along. On prom night all those years ago, I felt beautiful without question. Now, despite feeling fear, I am ready to walk through life one flat shoe at a time.