Glamour is an illusion, and an allusion too. Glamour is a performance, a creation, a recipe, but one with give. Glamour is elegance minus restraint, romance plus distance, sparkle sans naivete. Glamour is Grace Kelly, Harlow, Jean (picture of a beauty queen). Glamour is $3.99 on U.S. newsstands, $4.99 Canada. Glamour is artifice. Glamour is red lipstick, Marcel waves, a pause before speaking, and artfully placed yet seemingly casual references to time spent in Capri. Glamour is—let’s face it—a cigarette. Glamour is Jessica Rabbitt, and it’s Miss Piggy too. Glamour is adult. Glamour cannot be purchased, but it can’t be created out of thin air either. Glamour is both postmodern and yesterday. Glamour is an accomplishment. Glamour is magic.

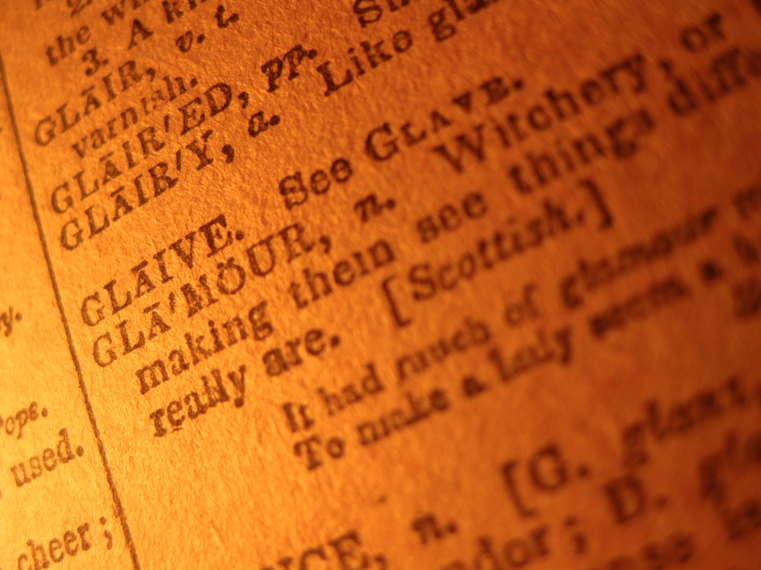

In fact, glamour began quite literally with magic. Growing from the Scottish gramarye around 1720, glamer was a sort of spell that would affect the eyesight of those afflicted, so that objects appear different than they actually are. Sir Walter Scott anglicized the word and brought it into popular use in his poems (“You may bethink you of the spell / Of that sly urchin page / This to his lord did impart / And made him seem, by glamour art / A knight from Hermitage”); not long after his death in 1832 the word began to be used to describe the metaphoric spell we cast upon one another by being particularly beautiful or fascinating. It wasn’t necessarily a compliment (“There was little doubt that he meant to bring his magnetism and his glamour, and all his other diabolical properties, to market here,” from an 1878 novel) but by the 1920s—not coincidentally, the time women started developing the styles that we now recognize as glamorous—the meaning had shed much of its air of suspicion.

Not that we’re wholly unsuspicious of glamour. Female villains in films are often impossibly glamorous, for as fascinated as we are with the artifice of glamour, we’re also a tad wary of it. Glamour keeps its holder at a distance, and it needs that distance in order to work; watch the magician’s hands too closely and you’ll spoil the trick. It’s unkind to glamour to call it strictly a trick, but neither is it inaccurate: On a person, glamour is a series of reference points that form its illusory quality. We perceive red lipstick and hair cascading over one shoulder as glamorous because we understand it’s referencing something we’ve collectively decided is glamorous. The same is true of glamorous looks with less direct artifice—say, a world traveler in a pith helmet and white linen—but in becoming a reference point, anything we code as glamour becomes artifice, even if it’s not about smoke and mirrors. It’s not hard to get glamour “right,” but since glamour is a set of references—a creation instead of a state of being—you do have to get it right in order to be seen as glamorous as opposed to pretty, polished, or chic. We don’t stumble into glamour; we create it, even if we don’t realize that’s what we’re doing. Call glamour a performance if you wish. It’s equally accurate to call it an accomplishment.

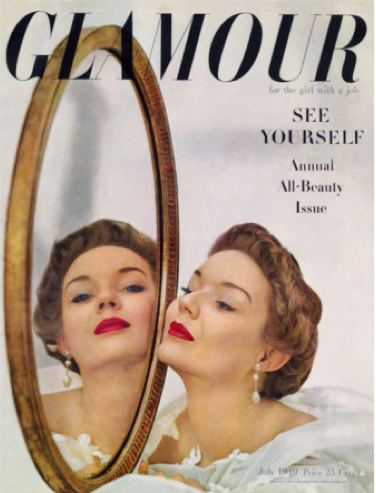

In 1939, glamour—rather, Glamour—took on an additional definition. In 1932, publishing company Condé Nast launched a new series of sewing pattern books featuring cheaper garments more readily accessible to the downtrodden seamstresses of the Depression; its more elite Vogue pattern line hadn't been doing well. Seven years later, Condé Nast spun off a magazine from this Hollywood Pattern Book called Glamour of Hollywood, which promised readers the “Hollywood way to fashion, beauty, and charm.” By 1941 it had shed “of Hollywood” and had already toned down its coverage of Hollywood in order to focus on the life of the newfound career girl; by 1949 its subtitle was “For the girl with a job.” That is, Glamour wasn’t about film or Hollywood or unattainable ideals; Glamour was about you. That ethos continues to this day: Glamour might have a $12,000 bracelet on its cover but will have a $19 miniskirt inside, and its editorial tone squarely targets plucky but thoughtful young women who want to “have it all.”

Some may argue that the rules and articulations of glamour are confining. They can be, when taken as feminine dictates, but they also make glamour democratic. It’s easy to aim for class or sophistication and miss the mark, for there are so many ways we can make unknowing missteps. But because glamour relies upon references and images, with a bit of thought and creativity almost anyone can conjure its magic—and unlike fashion, glamour doesn’t go in and out of style, so you needn’t reinvest every season. You can be fat and glamorous, bald and glamorous, poor and glamorous, short and glamorous, nerdy and glamorous, a man and glamorous. Perhaps most important, you can be old and glamorous. In fact, age helps. (Children are never glamorous; neither are the naive.) Glamour’s illusion doesn’t make old people look younger; it makes them look exactly their age, without apology. Glamour can channel the things we may attribute to youth—sex appeal, flirtation, vitality—but it also requires things that come more easily with age, like mystery and a past. Think of the trappings of adult femininity little girls reach for in play: not bras and sanitary pads, but high heels and lipstick, those two most glamorous things whose entire point is to create an illusion. A five-year-old knows that with womanhood can come glamour, if she wishes. She also knows it’s not yet hers to assume.

In case it’s not yet clear: I am a champion of glamour. That’s not to say I’m always glamorous; few can be, and certainly I’m not one of them. I like comfort far too much to be consistently glamorous. But I’m firmly in glamour’s thrall. When I am walking down the street (particularly 44th Street, in the general direction of an excellent martini) in something I feel glamorous in—say, a certain navy-blue bias-cut polka-dot dress with a draped neckline, clip-clip heels, a small hat, and the reddest lipstick I own—I feel a variety of confidence that I can’t channel using any other means. It’s not a confidence that’s superior to other forms of assurance, but it’s inherently different. It’s the feeling of prettiness, yes, and femininity and looking appropriate for the occasion. It’s all of those things, but the overriding feeling is this: When I am feeling and looking glamorous, I am slipping into an inchoate yet immensely satisfying spot between the public and private spheres. You see me in my polka-dotted ‘40s-style dress, small hat, and lipstick, and you may think I look glamorous—which is the goal. But here’s the trick of glamour: You see me, and yet you don’t. That is, you see the nods to the past, and you see how they look on my particular form; you see what I bring to the image, or how I create my own. Yet because I’m not necessarily attempting to show you my authentic self—whatever that might be—but rather a highly coded self, I control how much you’re actually witness to.

Now, that’s part of the whole problem we feminists have with the visual construction of femininity: The codes speak for us and we have to fight all that much harder to have our words heard over the din our appearance creates. But within those codes also lies a potential for relief, for our own construction, for play, for casting our own little spells. That’s true of all fashion and beauty, but it’s particularly true of the magic of glamour.

I promise not to play tricks on anyone. But forgive me if, every so often, I might want to use a little magic.

_________________________________________

Stay tuned for part II tomorrow, in which an author and renowned national columnist, a multidisciplinary artist and satirist, a four-time novelist with a bent toward otherworldly enchantment, and a publicist who's one of the "cultural gatekeepers in the literary world" share their own thoughts on the concept of glamour.