Tim Burton's Big Eyes makes a strong case that Walter Keane was a first-order marketing genius and his wife Margaret, whose paintings he appropriated and promoted as if they were his own, used his marketing talents up until the moment she could safely dispense with them. Given that Margaret Keane apparently cooperated with the making of Big Eyes (she painted Burton's then wife Lisa Marie in 2000, and I think she appears at the end of the film alongside Amy Adams, who plays her), this seems sort of surprising. On the surface, the movie tells the story of her artistic reputation being rightly restored, but that surface is easily punctured with a moment's consideration of the various counternarratives woven into the script. Then we are dealing with a film about a visionary who turned his wife's hackneyed outsider art into one of the most popular emblems of an era and who has since been neglected and forgotten, despite inventing art-market meta-strategies that have since become ubiquitous. The movie seems to persecute Walter because the filmmakers believed it was the only way they could get us to pay enough attention to him to redeem him.

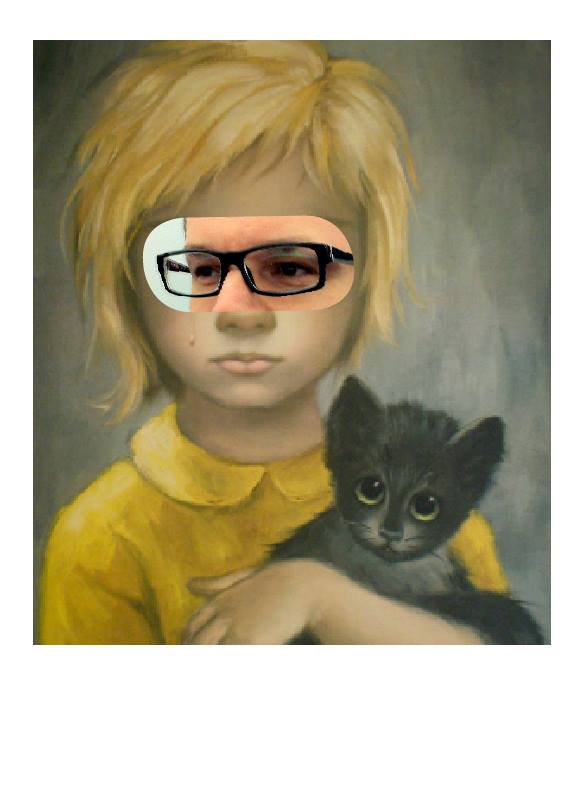

I went in to see Big Eyes expecting a cross between Burton's earlier Ed Wood and Camille Claudel, the biopic about the sculptor whose career was overshadowed by her romantic relationship with Rodin, whom she accused of stealing her ideas. That is, I thought it would be about how female artists have struggled for adequate recognition, only played out in the register of kitsch pop art. I figured Burton would try to capture something of whatever zany, intense passion drove Margaret Keane to make her "big eye" paintings, much as he had captured Ed Wood's intensity in the earlier film. We would see a case made for the legitimacy of Margaret's work, which is now often seen as campy refuse, maudlin junk you might buy as a joke at a thrift store, at the same level as Love Is... or Rod McKuen poetry books.

But Burton doesn't make much of an effort to vindicate Margaret on the level of her art. No explanation is suggested for why she paints or why audiences connected to her work. Rather than giving the impression that no explanation is necessary, that its quality speaks for itself, this omission has the effect of emphasizing the film's suggestion that the significance of her painting rests with the innovative job Walter performed in getting people to pay attention to it, operating outside the parameters of the established art world. Meanwhile, Margaret's genius remains elusive, as unseeable as it was when Walter effaced it. Margaret is a bit of a nonentity in the film, locked in a studio smoking cigarettes and grinding out paintings at her husband's command, much as if she were one of Warhol's Factory minions, while Walter is shown as a dynamic, irresistible figure who comes up with all the ideas for getting her work to make a stamp on the world. In fact, in the script, Burton likens Walter to Warhol multiple times and the movie even opens with a Warhol quote (from this 1965 Life article) in which he praises Walter Keane: "I think what Keane has done is just terrific. It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.”

Since this quote came before seeing anything of the story, I took it as Burton's attempt to use a name-brand artist's imprimatur to validate Margaret's work in advance for movie audiences who possibly wouldn't read any irony in Warhol's statement — Burton could laugh at his audiences and show his contempt for their expectations by rotely fulfilling them, as he had with Mars Attacks and the Planet of the Apes remake. But (as usual) I was being too cynical. Afterward, I started to think Burton was in earnest in choosing this quote, and that Big Eyes is instead subverting the expectations liberal audiences might have of it being a stock feminist redemption story. It mocks those audiences, mocks the indulgence involved in using depictions of the past to let ourselves believe we have now somehow transcended the bad old attitudes of sexism. The somewhat smug and self-congratulatory view that "Nowadays we would accept Margaret Keane as a real artist and see through Walter Keane's tricks" is complicated by the fact that Margaret's art is kitsch and that Walter's tricks come not at the expense of art but are instead the sorts of things that nowadays chiefly constitute it.

Margaret is depicted as the victim of Walter's exploitation, but that view is too simplistic for the film that ostensibly conveys it. It makes Margaret passive, intrinsically helpless, easily manipulated. So simultaneously, Big Eyes gives a convincing portrait not of Margaret's agency, as you might expect, but of Walter as a passionate, misunderstood genius, a Warhol-level artist working within commercialism as a genre, doing art marketing as art itself with the flimsiest of raw materials and executing a conceptual performance piece about identity, appropriation, cliches, and myths about creativity's sources that spanned a decade. When the script has Walter claim having Walter claim that he invented Pop Art and out-Warholed Warhol with his aggressive marketing strategies, we can read it "straight" within Margaret's redemption story as a sign of Walter's rampant egomania. But the film actually makes a solid case for that being plausible, stressing how Keane was able to bring art into the supermarket before Warhol brought the supermarket into art.

Similarly, when Margaret discovers that the Parisian street scenes Walter claimed were his own while wooing her were actually painted by someone else and shipped to him from France, she is shocked, and we are seemingly supposed to share in this shock and feel appalled. But it makes as much sense to want to applaud his audacity and ingenuity, his apparent ability to assemble and assume the identity of an artist without possessing any traditional craft skills at all. He's sort of the ur-postinternet artist.

All of Big Eyes is shot as if the material has been viewed naively through the child-like big eyes of one of Margaret's subjects, a perspective from which Walter's acts just seem selfish and insane. But Burton is careful to allow viewers to regard the action from a more sophisticated perspective, which reads between the lines of what is shown and looks beyond the emotional valences of the surface redemption story being told. Margaret's character always acknowledges Walter's marketing acumen in the midst of detailing his misdeeds, and she never explains why she helped Walter perpetrate his fraud, other than to say, "He dominated me." From what Burton shows and has Margaret say, this domination is less a matter of intimidation than charm. As awful as his behavior might have been in reality, Walter is little more than a cartoon villain in the film's melodramatic domestic scenes; the misdeeds Burton depicts are Walter's getting drunk and belligerently accusing one of Margaret's friends of snobbery for rejecting representational art, and his flicking matches at Margaret and her daughter when he is disappointed about her work's reception.

Of course, Walter's primary crime is making Margaret keep her talent a secret (an open secret, apparently) — "from her own daughter!" even. He capitalizes on a sexist culture to take credit for Margaret's ability, and then uses the specter of that sexist culture to control her, while more fully enjoying the fruits of what her ability brought them — the fame, the recognition, the celebrity hobnobbing, and so on. But Big Eyes also makes a point of undermining that perspective to a degree, making it clear that Margaret (in part because of that same sexist culture) never would have had the gumption to make a career out of painting without Walter's support, and certainly she wouldn't have been able to follow through with all the self-promotion necessary to sustain an art career and allow it to thrive. We are told that she didn't want the spotlight; at the same time we are supposed to see her being denied the spotlight as part of her victimization. Walter helped created conditions in which Margaret could paint as much as he exploited the inequities of those conditions. And Margaret triumphed in ways that go far beyond the limited accomplishment of earnest "self-expression."

During the trial scene, which is supposed to be Margaret's ultimate vindication, one instead gets a sense through her testimony, and Walter's outlandish performance as his own lawyer, that he will stop at nothing to put across his vision of the world and himself, despite not having any talent with traditional materials of representation. Doesn't that make him the greater artist, the film seems to suggest, that he can use other people as his medium? All Margaret can apparently do is the parlor trick of making a big-eye painting in an hour in the courtroom. Whereas Walter could get Life magazine to interview him and tell his story, he could contrive elaborate background for how he suddenly came to paint waifs and kittens, and he could get his wife to willingly make all of his work for him and let him sign it as his own.

It is hard to walk away from Big Eyes without wondering just how much Margaret and Walter collaborated on the character of "Keane," the artist who made compelling kitsch, and it's hard not to feel sorry for him when before the ending credits we are shown a picture of the real Walter Keane, with text explaining how he died broke and penniless while he continued to insist on his own artistic genius. I wondered if in working with Burton, Margaret wasn't still covertly collaborating with Walter, muddying the waters around their life's work and letting some ambiguity flourish there. This impression, more than anything depicted explicitly in the film, gave me the strongest sense of Margaret's character, beyond cliches of resiliency and self-actualization.