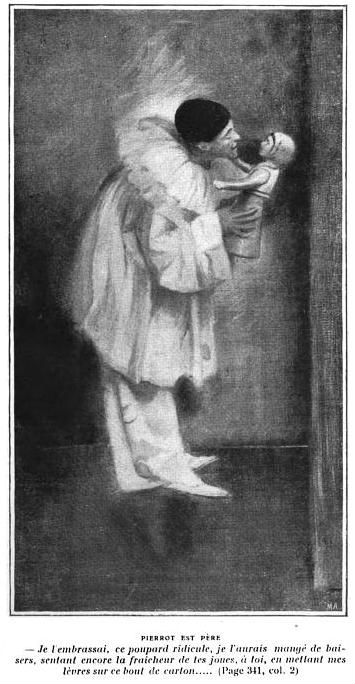

Illustrations from Je sais tout (1907)

Originally performances that did not take place on a stage, pantomimes completed the most memorable ancient Roman gatherings. When Cicero gave a dinner he had an elocutionist read a dialogue of Plato or a tragedy of Euripides. When Caligula hosted a feast he loosed on his guests defanged and declawed lions and tigers.

He who takes up the profession of mime while still a child deserves pity. Jean-Gaspard Deburau met such a fate. His soldier-turned-showman father dragged his half-starved, ragtag troupe hither and yon to entertain audiences with acrobatic feats and jaw-dropping balancing acts. The delightful pantomime of the impresario's son, however, proved the troupe's most popular attraction. The peregrinating performers eventually came to settle in one spot, winning a place at Paris's Théâtre des Funambules thanks to the youth's uncommon talent.

The clever mime soon found himself the toast of the capital

"The uttered part of a man's life ... bears to the unuttered, unconscious part a small unknown proportion. He himself never knows it, much less do others." -- Sir Walter Scott.

. Crowned the "King of the White-Faced Harlequins," he heard journalists sing his praises. Writers and artists discovered in his performances great meaning. "The most perfect actor who ever lived!", gushed Théophile Gautier. George Sand wined and dined him, and Charles Baudelaire analyzed his method. Deburau appealed especially to Paris's street sweepers and factory workers, who nightly packed the cheap seats to witness Pierrot, Deburau's most beloved character, caper about in a frilled collaret or a baggy cotton blouse and black skullcap. He played the buffoon, the glutton, the loafer, the revolutionary. He boasted a "superabundance" of gestures, of leaps. By the simplest methods he evoked the audience's hopes, sorrows, joy and anger. Critics fused Pierrot with the people; when he took the stage he and they stood "like two twin souls."

Yet mirthful expressions often mask dark dispositions. Deburau and Pierrot shared little in terms of personality. One day while strolling the boulevards with his family, Deburau happened upon a street urchin who recognized him as the celebrated mime. "Pierrot!," he cried. Angered to hear himself identified as his alter ego, Deburau raised his very real cane and swung it at the child's skull, which cracked like a nut. The child died instantly.

The "Deburau effect" now refers to directing the listener's attention to an inaudible sound that, once heard, ceases to elicit interest.

The trial that followed drew citizens from their parlors, cafes and bars. Throngs gathered at the courthouse. "Here at last the great Pierrot will speak!," men and women whispered. And speak the great mime did -- but only to offer testimony on his own behalf. His motives he did not reveal, even after he won acquittal. As to why such a talented man should kill a child, Deburau's biographer Tristan Rémy conjectured that his subject's persona had something to do with it. "When he powdered his face, his nature, in fact, took the upper hand," Rémy observed. "He stood then at the measure of his life -- bitter, vindictive, unhappy." Deburau suffered for his mute art, and did so in silence. And though his skills carried him to the heights of fame, they could not fetch him from the depths of despair.