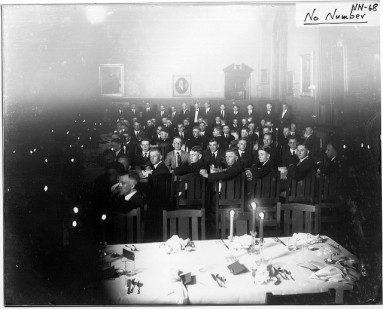

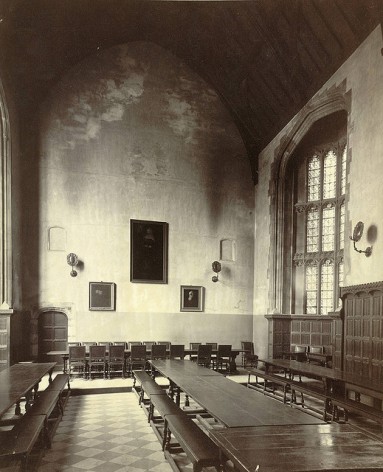

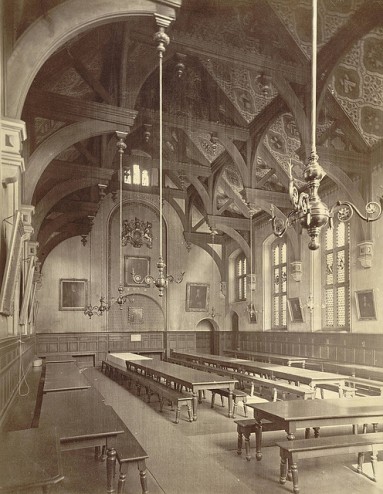

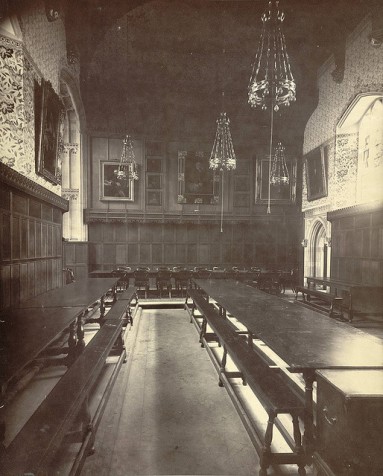

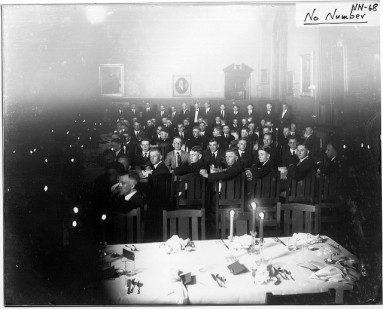

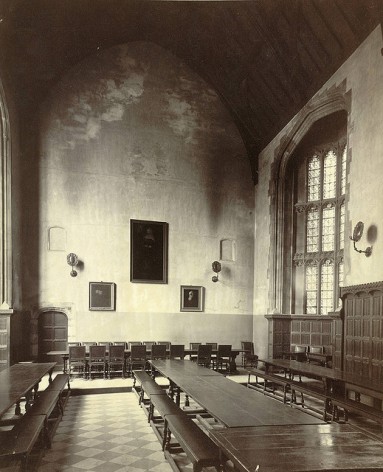

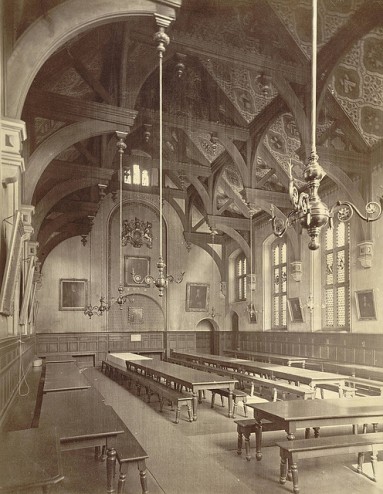

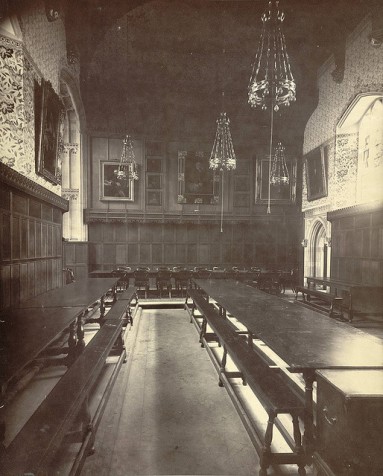

Higher learning and higher caloric intake have long gone hand in hand

Photographs of college dining halls, ca. 1870

"The true university of these days is a collection of books." --Thomas Carlyle

My first year of college I managed to keep off the dreaded "Freshman 15" by living on Grape Nuts, soy milk, orange juice, and gin. Not exactly brain food, I admit, but I faced limited options. In my dorm room I had a minifridge and microwave, and that's it (no hotpots or -plates allowed). I didn't own a car, and the closest supermarket was miles from campus. The student union was your typical gauntlet of fast food stands complemented by serving lines ladling out overpriced tray-fuls of mashed potatoes, corn niblets and chicken parts. A food co-op operated nearby, but its horn o' bowel-quickening plenty — carob almond mounds, sprouted spelt bagels, tempeh salad sandwiches — asked prices that meant only the very rare splurge. Chronically short of cash, I decided that a nice buzz was as important as a full belly and took the practical expedient to achieving both.

"The extremes of the total annual expenses of students at Harvard, which may be considered the representative of city colleges, -- like Yale, and the colleges in the city of New York, -- are about $450 and $3,000. But the poor, economical student, who stints himself to $450, lives in narrow quarters and eats the cheapest food; and the rich student, spending $3,000, lives as luxuriously as the wealthiest New York or Boston families." --Charles Franklin Thwing, American Colleges, Their Students and Work (1883)

Come flu season, I began to doubt the wisdom of a booze and breakfast cereal diet. As luck would have it, my university sat squarely in the Sun Belt. The yards of nearby tract homes bristled with citrus and other fruit trees. These my then-boyfriend and I would raid. After an evening's slinking through alleys to pluck suburban bounty, we'd return to my room, our backpacks stuffed with pounds of pears, pomelos and oranges.

"'Ah no,' said an old son of Brown some days ago, 'college life isn't what it used to be at Brown. They were great days when I was an undergraduate, great days, great days. Still, I'm rather glad my son doesn't run the risk of a broken head and a midwinter swim in the Seekonk, as I did, and on the whole, things seem to have changed for the better since my day. But you boys don't have to study as we did. No, sir; you don't know what study is.'" --Dallas Lore Sharp, "Undergraduate Customs of Brown" (1895)

The sweet savor of those fresh-squeezed freshman days turned out to have a bitter finish. My then-boyfriend, I later learned, developed a stomach ulcer from our citrus regimen. Perhaps you could make the case that we suffered some sort of institutional neglect, especially if you bear in mind that, had we entered university a century or so before, more care would have gone into our feeding.

Colleges and universities of yesteryear developed firm ideas about student nutrition, and they devised iron rules for carrying them out. The steward of Rhode Island College, for example, saw that the dining hall provided "three good, sufficient, well-cooked meals every day." Though good and sufficient, they were somewhat lackluster, consisting mostly of such New England mainstays as "salted beef and pork, with peas, beans, roots, &c." Roasted meat appeared only as an occasional treat.

"Mr. Burke said at Chelsea College dinner, a poor French cook was persecuted by the mob at Edinburgh as a Papist. Said young Burke, "They had taken him for a frier." --James Boswell, Boswelliana (1876)

Students attending Pennsylvania's Haverford College had it better. Strawberry shortcake succored them during exam week, and most evenings "green apple pies of liberal dimensions" appeared at table. Yet "liberal" appears a somewhat subjective appraisal; a ravenous bunch, Haverford students demanded third and fourth servings so frequently that the school's superintendent felt moved to intervene. "We aim to furnish each student with two pieces of pie," he decreed: "further than that we do not go."

Vassar girls made Haverford boys look positively abstemious. In 1887 a reporter for the Michigan Argonaut investigated the refectory of the upstate New York women's college. He found that consumed there daily were 600 eggs, 50 pounds of butter, and 350 quarts of milk. Greasing morning griddle cakes required "two tubs of butter," and every Friday saw the disappearance of some 75 shad. Vassar girls even did dessert big, nightly demolishing 55 quarts of ice cream and clamoring for more.

"It is said that the college dinner at Cambridge yesterday partook largely of the character of an 'indignation meeting.' A 'comeouter' states that some of the poultry was very lively, and in the course of the muss escaped out of the windows." --Transactions, Volume 18 (1917)

Curbing such gluttony presented a tough challenge, but faculty at some colleges felt themselves equal to it. Unbecoming dining habits they sought to banish by adding table manners to the curriculum. At Pennsylvania's Bristol College students were compelled to await the end of the presiding professor's blessing before tucking into their suppers. Yet even after the benediction "the strictest proprieties" remained in force, any violation of which met with "penalty ... according to the aggravation of the case."

"WIFE: Well, well, I will allow that there was a college dinner! But you must admit that it isn't natural for a man to come home after midnight." -- From "The Silent System: A Sketch in One Act" (c. 1889)

Whatever their severity, penalties didn't do much to dampen the enthusiasm most students had for university food. Christopher Morley recalled fondly Oxford's Kitchen Tariff, with its "gloatingly magnificent syllables" sounding out everything from "Devilled Kidneys" and "Chops with Chips" to an electrifying assortment of jellies, compotes, trifles, fruit, and creams. And though M.F.K. Fisher thought the food at her college mostly bad (a glimpse into the refectory kitchen revealed to her little more than "empty gallon cans labeled Parsnips"), she relished her Sunday breakfasts of "really delicious hot cinnamon rolls." (But even they weren't enough to keep her from the "ginger ale, rolls, cream cheese, anchovy paste, bottled 'French' dressing, and at least six heads of the most beautiful expensive lettuce" she would gobble down in furtive nighttime binges.)

Holidays proved supremely binge-worthy occasions. St. Norbert's feast day, for example, offered St. Norbert's College a fitting excuse for setting a lavish spread. After a vigorous afternoon of baseball games, concerts, and eloquent sermons on their namesake's virtues, students dug into "Lemon Cocktail, Celery Broth with Veal Balls, Fricasee of Chicken, Baked Veal Loaf, Cabbage Salad, Sweet Pickles, Stuffed Olives, Mashed and Scalloped Potatoes, Sugar Corn La Creme, String Beans, Fruit Jello, Strawberry Shortcake, Ice Cream, Tea, Coffee, Wheat, Raisin and Cocoa Bread."

Legend has it that the custom of the Boar's Head Dinner started some 500 years ago. A scholar of Queens' College was walking in deep meditation in a neighboring forest when he was attacked by a boar. He saved himself -- and killed the boar -- by throwing down its throat the Aristotle he was just reading, with the remark: "Graecum est"-- "It's Greek!" In honor of his miraculous escape the Boar's Head Dinner was introduced at Christmas, and a bust of Aristotle adorns to this day the large fireplace in the College Hall.

"For the practice in putting up a boar's head the beginner should bone and cook pigs' heads to serve cold, until he has become familiar with the methods of making them good and of putting them in shape." --James Whitehead, Cooking for Profit (1893)

As lavish as was the St. Norbert feast, it paled in comparison to the pigging out characteristic of Oxford's "Boar's Head Dinner," a 500-year Christmas tradition still observed today. After much merrymaking among the students, professors marched in solemn procession through the Hall of Queen's College, which was bedecked with greenery and warmed by a "monstrous fire." Behind them trailed three bearers holding aloft a boar's head. A crown of bay leaves, rosemary, and flags displaying the college's arms encircled it. Trumpets sounded, and sung to herald its arrival was the "Boar's Head Carol":

"Then the grim boar's head frown'd on high, / Crested with bays and rosemary." --Sir Walter Scott, "Ancient Christmas" (1877)

The Boar's head, as I understand, / Is the bravest dish in the land; / Being thus decket with gay garland, / Let us servire cantico.

The song over, faculty took the crown apart and distributed it among the crowd. One man reporting on the feast for The Gentleman's Magazine was so swept up in the ceremony that he fancied himself gathering "strange glimpses" of "an early race of hunters and herdsmen in Central Asia ... among whose sacrificial customs the Sun-Boar ... played a great part at winter solstice." In this case, journalistic objectivity fell before fanciful projections, which goes to show just how thoroughly the Boar's Head ritual was feast for all the senses.

"For my own part, I believe that whatever may be the case for the morning and evening meal, the character of the food taken during the working hours of students should be such as to sustain the supply of force-producing material in the blood, without requiring a larger per cent. of the force already at hand to convert the food eaten into new force-producing material." --Edward Atkinson, The Science of Nutrition (1896)

With the twentieth century came a more staid, scientific approach to college dining. Modern cafeterias replaced stodgy refectories, and meals served family style ceded to a la carte menus. New Hampshire College boasted a dining room "modern in every respect," chief among which was "seating capacity of 300." Wisconsin's Beloit College redesigned its dining room for purposes of offering "the greatest use and convenience to the entire College community." Men gathered there, and in so doing contributed "as largely as possible to the College life." Similarly interested in masculine congress, Texas's Baylor College trumpeted varied menus, moderate prices and good service as its cafeteria's cardinal virtues. The cozy quirkiness of dining halls past deemed a whimsical inefficiency, emphasis came to lay on standardization and good nutrition.

Recipe for "College Pudding" from The Menu Cookery Book (1885): "2 cups of bread crumbs, 1 cup of currants, 1 cup of suet cut very fine, 2 eggs beaten and a little moist sugar. Bake in cups, turn out, and serve with wine sauce round."

Standardization still marks the dining experience at most schools. Good nutrition, however, seems to have lost out to corporate interests. With many universities and colleges (not to mention prisons) serviced now by companies like Aramark and Sodexho Marriott, it's unlikely we'll see a return to those quirkier feasts. But thanks to student demand for such things as local produce and fair working conditions for cafeteria staff, some colleges have once again taken food preparation in-house. It's a change long overdue. I know I would've welcomed more wholesome food in my undergraduate diet, and I'm sure my Tums-popping ex-boyfriend would have too.