By Robert Davis

Beauty and self-care has always been in conversation with contemporary politics, especially regarding race, gender, class, and privilege. While the concept of “self-care” has taken a prominent place in American society since the 2016 election, in the late 19th century, an explosion of cheap, readily available print advice books encouraged regular Americans to improve their bodies for greater health and well-being by conforming to white, middle-class beauty norms. One such book, the popular 1882 How to Become Beautiful; or, Secrets of the Toilet and of Health reveals how Americans framed self-care as an imperative that encouraged women to forsake the public sphere to strive for an unattainable, high-stakes ideal at home.

What makes How to Become Beautiful unique is that it was not published in mainstream forums like middle-class women’s magazines. Instead, a dime novel press printed it as one of a series of “how-to” books. Others titles in the “Ten Cent Library” included How to Do Sixty Tricks With Cards, How to Become a Scientist, and How to Do It. Today, we generally consider dime novels to have been the purview of young adult men, but the existence of How to Become Beautiful suggests that women read these books as well. When publisher Frank Tousey released the anonymous How to Become Beautiful, he had every expectation it would influence thousands of female readers. The book offers general lifestyle advice and home remedies ranging from acne treatment and headache drops to toothpaste and lip balm. With these tips, the reader could transform into how “nature intended you to look.”

While appearing to be a collection of benevolent tips, How to Become Beautiful is actually a powerful persuasive tool based on a white supremacist vision of the world. It frames its lessons within an evolutionary argument: “Civilization has taken much from both manhood and womanhood … in the same ratio as men and women become civilized and cultivated according to the formulas of modern society, do they fall off in physical beauty.” In the late 19th century, Americans saw technological advances as signs that their society was evolving to greater degrees of civilization.

At the same time, Americans obsessively worried that "too much" civilization made them weak. They believed that progress created “nervous disorders” like neurasthenia and hysteria, which, if unchecked, could lead to individual illness and social degeneration. How to Become Beautiful responds to these concerns by arguing that the role of women in this race for the survival of the fittest is to increase their beauty. The book became an essential resource for American women to maintain their physical connection to an imagined Anglo-European civilization.

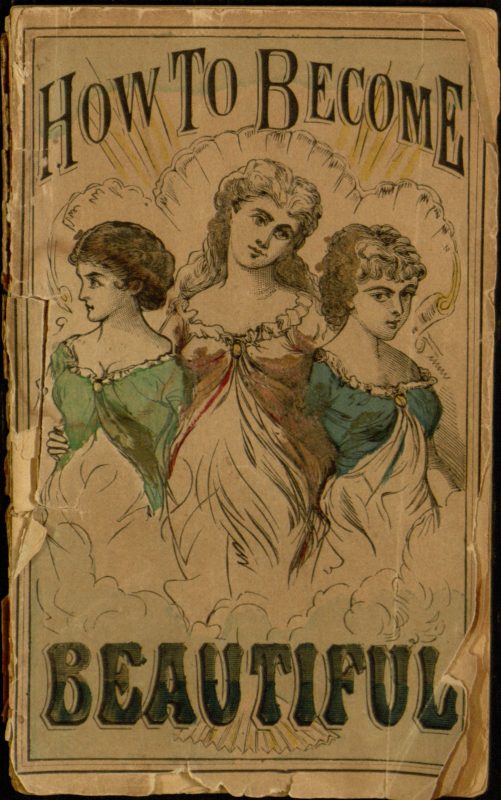

How to become beautiful; or, secrets of the toilet and of health (1882). Villanova Digital | Creative Commons

How to Become Beautiful’s cover shows three women in modest dress emerging, Venus-like from an open clam shell. Framed by heavenly light, their hair and complexion are perfect. They present themselves as idealized objects fit only for a pedestal. Like the images, the text also references classical Greek and Roman statuary as examples of what beautiful gendered bodies used to look like before the oppressive advance of civilization: “Consequently, when we behold the statues of Apollo Belvedere and the Venus of the Vatican, both made from living models centuries ago, we can comprehend our great decline in physical beauty.” This culture of beauty drew on well-circulated images in the natural sciences. The Apollo Belvedere statue was an often-invoked standard of whiteness and beauty in the mid-to-late 19th century. Most famously, it appeared in Josiah Nott and George Gliddon’s discredited 1854 book of racial pseudoscience, Types of Mankind, to represent whiteness as the pinnacle of human evolution. How to Become Beautiful’s use of the statue as an exemplar makes it clear that civilized “beauty” excludes women of color.

After casting beauty as the front line of a pitched battle for civilization, the book reassures the presumed female reader that beauty is easily attainable by aspiring to a strictly normative lifestyle. The book’s fundamental advice is: “Be temperate in all things.” To succeed, the reader must submit her body, emotions, and mind to a narrow range of thoughts, feelings, and experiences. She must moderate her habits by staying away from alcohol and tobacco, having regular, plain meals, and following regular bedtimes. She should keep all of the rooms of her home the same temperature and avoid cities. The book connects a mental regime to a physical one by commanding the reader “do not get excited at anything,” since this may “leave a wrinkle either in the mind or body,” which, it warns, “can never be eradicated.” Any excess leads to a mental or physical blemish, marring the body forever. To stay wrinkle-free, the reader must only “read cheerful books” because “fretting and looking on the dark side of things puts wrinkles on the face, exciting the brain unnecessarily” and lays “the foundation for disease.” It is of the utmost importance, above all, to “avoid all unnecessary excitement.”

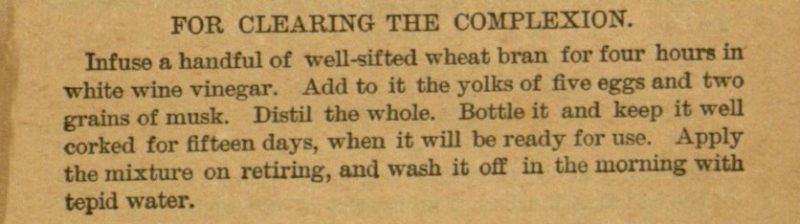

Examining the How to Be Beautiful’s recipes reveals that much of the work of maintaining the social ideal of beauty required women’s labor. In addition to maintaining the home, women would need to devote considerable labor to crushing, mixing, steeping, and otherwise treating the varied ingredients. For example, a recipe “For Clearing the Complexion,” would take hours of preparation and more than two weeks of waiting.

How to become beautiful; or, secrets of the toilet and of health (1882). Villanova Digital | Creative Commons

It would be almost a decade before beauty products would be mass-produced and readily available through mail order. In the meantime, beauty culture was maintained by women’s work.

Some recipes could be invasive or dangerous. Since large pupils were considered beautiful, the reader was told to apply drops of sulphate of atropia mixed with water into the eye. Most of the recipes rely on some kind of moisturizer and floral perfumes, as well as corrosives and assorted chemicals. There are copious recipes for toothpaste, often named after Napoleon, which usually involve a mixture of ground chalk and cuttlefish bone, with the addition of opium for toothaches. A central focus in the book was how to maintain one’s hair, with recipes ranging from dandruff treatment to making Bear Grease for styling. More intense treatments include putting borax, ammonia, beef marrow, or quicklime into one’s hair. While many of the book’s so-called cures would strike us today as somewhat revolting, this only reinforces the historical contingency of beauty and beauty products.

Overall, How to Be Beautiful demonstrates the cultural construction of beauty as well as the material culture of how it was maintained. It was not an arcane manual. At ten cents and available through mail order, it was readily accessible for all classes. Unlike the American elite, not everyone could afford to go to the country to restore their health and beauty, but many people could access oils, chemicals, and chalks to beautify at home. Books like How to Become Beautiful democratized beauty, but only by spreading the gospel of white, evolutionarily-motivated, Anglo-American virtue. In this context, self-care functioned as a mandate for social conformity, making its subjects buy into a worldview that equated looking good with being morally — and evolutionarily — perfect.

In contrast with 19th century beauty ideals, the idea of taking care of one’s own body and mind has been claimed as a resistance practice since protest movements in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1988, Audre Lorde proclaimed that self-care can be a radical act, especially for black women, writing that “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” The emergence of a culture of self-care has given rise to a parallel consumer culture, with endless “top-5” lists and tailored products. Yet, it also speaks to the fundamental possibility of attending to the self as a resource for resisting a hostile political climate and its resulting microaggressions. The fashion industry still dictates that women spend millions of dollars and countless hours to try to look “good” in a normative sense, but, maybe, 100 years after How to Become Beautiful, we are able to not only reimagine beauty and self-care, but see its radical possibilities.

Further Reading

Michael Denning, Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America (London: Verso Books, 1987).

Kathy Peiss, Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011 ed.)

The Josephine Long Wishart Collection: Mother, Home, and Heaven, Online Exhibit: Beneath the Painted Face: The Rise and Evolution of America’s Cosmetics Industry

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.