By Jenna Tonn

Two things strike me whenever I teach my undergraduate seminar “Women in American Medicine.” First, my students, many who have medical ambitions of their own, are shocked by the well-documented history of the medical establishment’s discrimination against women, from actively excluding midwives from the bedside in the 19th century to enforcing the criminalization of abortion in the 20th. Second, they are even more surprised that the history of nursing is much more complicated than one might imagine given depictions of nurses in popular culture.

Images of nurses as selfless ministering angels predominated in the 19th and early 20th centuries and were replaced during World War II with representations of sexy pin-up nurses as seen in novels, film, and television. During this period, nursing as a field professionalized and struggled to balance its legacy as gender-stereotyped “women’s work” with a commitment to scientific training, technical competency, and authority at the bedside. In this context, nurses had the opportunity to leverage cultural associations between femininity and caregiving to pursue paid employment. But, as members of a feminized profession, they also had to confront grueling labor demands, chronic undercompensation, and devaluation within medical hierarchies.

Nursing emerged from the daily responsibility of women’s domestic labor. Historians often point to the Civil War as an inflection point in this history. During the 1860s, white, middle-class reformers like Louisa May Alcott volunteered to serve in poorly equipped, unsanitary military hospitals and returned home to argue that humane medical care could not be delivered without investing in formally training women as nurses.

The historian Susan Reverby has shown that nursing training programs developed in the 1870s and 1880s, many inspired by the methods and ethos of Florence Nightingale. The romantic ideal of the “womanly” trained nurse belied the reality of exploitative labor structures and paternalistic codes of behavior. It is important to note, however, that fissures between nursing ideals and daily practice circulated before the Civil War and outside of trained nursing. For example, Sharla Fett documents how sanitized visions of white women’s nursing work on southern plantations obscured the fact that enslaved women performed most of the everyday health work for both enslaved and planter communities. In both cases, women did the dirty work—dosing and administering medicines (often heroic medicines that induced significant effects), cleaning up bodily fluids, providing care at all hours, cleaning and sanitizing instruments, beds, wards, and sheets, and tending to wounds, blisters, and bleeding.

After the establishment of nurse training programs, arguments about class and race emerged within professional nursing communities. Nineteenth-century nursing programs worried about damaging their reputations by admitting young, uneducated, immigrant women. In addition, before the rise of the hospital as the primary site of care, many trained nurses working in private-duty (living and working in a private home) demanded a place at the family dinner table to demarcate themselves from household servants.

In the 20th century, white, middle-class visiting nurses, trained in the latest methods of sanitary reform and home economics, sought to bring the “gospel of germs” to poor, working-class immigrant families, who lived in tenement houses. These nurses envisioned teaching new scientific methods of cleanliness and sick care as part of a larger project of encouraging assimilation into American society.

At the same time, as Dorothy Clark Hine has pointed out, qualified black women were largely excluded from established nurse training programs due to white racism and the racial segregation of healthcare. Instead, they contributed to the development of black hospitals and nurse training schools, which were dedicated to providing medical care to the black community. While traditional gender expectations allowed women to seek meaningful employment as nurses, they also revealed how relationships between women fragmented along racial and class lines.

Images of nurses in popular culture often overlook these complicated dynamics and focus instead on either reifying gender expectations or transgressing them. Since nursing work requires women coming into close, physical contact with male bodies, nurse training programs often included strict codes of conduct (including dress codes) in an effort to prevent personal relationships with patients.

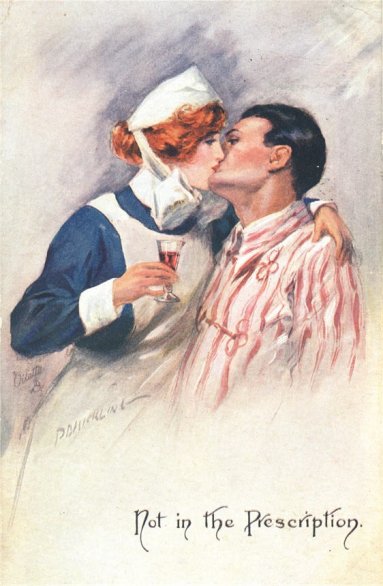

Regulations reinforced ideals of professionalism within the nursing community but did little to stop patients and medical practitioners from sexually harassing nurses. During World War I, depictions of the nurse as an attentive mother, caring angel, and patriotic fighter fortified these established professional norms. Some images, however, traded on nurses’ sexual availability, situating questions of sexuality and desire within chaste narratives about love and marriage.

"An Angel of Mercy." Postcard by Hal Hurst, 1917. (National Library of Medicine I Public Domain)

Some images, however, traded on nurses’ sexual availability, situating questions of sexuality and desire within chaste narratives about love and marriage.

"Not in the Prescription." Postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons, ca. 1914-1918. (National Library of Medicine I Public Domain)

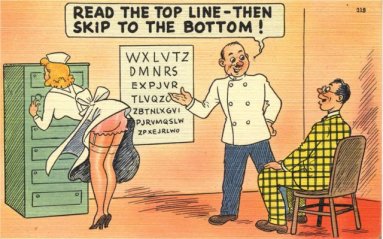

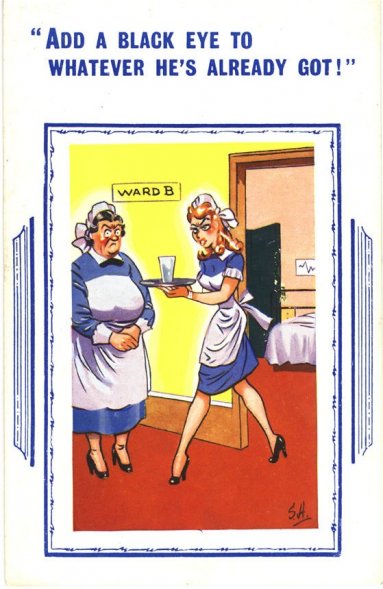

During World War II, nurses were recast as pin-up girls. Barbara Melosh and Beth Linker have argued that popular conceptions of the nurse during this period reveal a new anxiety about the rising status of nurses. Nurses were celebrated for the work they did during wartime at home and abroad. American hospitals reorganized at mid-century to incorporate new technologies and specialty services, such as neonatal intensive care units and rehabilitation wards that relied on nurses’ growing technical expertise.

In these settings, high-status nurses provided care for low-status sick, injured, or disabled men, which upended traditional gender roles. Cultural observers responded with novels, films, cartoons, and television shows that featured sexually transgressive depictions of the young, available “sexy nurse” like Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan in M*A*S*H or the hardened, spinster “battle-axe” such as Nurse Ratched.

"Read to the top line-- then skip to the bottom!", ca. 1919-1952. (National Library of Medicine I Public Domain)

"Add a black eye to whatever he's already got!", ca. 1950. (National Library of Medicine I Public Domain)

Stereotypes about nurses continue to circulate in popular culture. In conversations with my students, this is most striking in the context of the thousands of “sexy nurse” and “naughty nurse” Halloween costumes available on Amazon. According to Juliet Lapidos, the phenomenon of sexy costumes can be traced to the 1970s when a neighborhood Halloween parade in Greenwich Village converged with New York’s gay culture and transformed into an annual gender-bending costume extravaganza. Although these original costumes were homemade, retailers started marketing and selling their own versions in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Scholars are not sure why “ultrasexy” costumes have become so popular among women in the past several decades. Is the gendering of the Halloween costume market informing women’s choices? Is dressing like a sexy nurse conforming to male fantasies? Or, are women actively seeking out opportunities to play with personal expressions of sexiness, femininity, and desire? Whatever the reason, naughty nurse costumes are part of a longer history of associating nursing with the sexual objectification of women.

Advocacy organizations like The Truth about Nursing work to challenge these stereotypes. They argue that objectifying nurses undermines the work that women and men do as trained medical professionals, play a role in the underfunding of nursing research and education, and encourage children to associate nursing with low-status “women’s work.” Along with educating the public about nursing’s important role in health care delivery, The Truth About Nursing protests against marketing campaigns like Sketchers’ 2004 sneaker advertisement featuring Christina Aguilera as a “naughty nurse.” Similarly in 2005, the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario fought against Virgin Mobile Canada’s ad campaign that, according to the American Journal of Nursing, “feature[ed] ‘naughty nurse’ models ready to help young wireless consumers avoid a mock venereal disease, the ‘catch,’ which represented Virgin’s rivals.”

In many ways, the circulation of nursing stereotypes mask more complicated stories about the historical relationship between labor, gender, and power in modern medicine. Perceptions of the nurse as an object of interest—whether “naughty” or angelic—serve to distract us from contending with the real ways that professional caregiving remains central to our experiences of health and illness.

Further reading

Patricia D’Antonio, American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History

Darlene Clark Hine, Black women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950

Susan Reverby, Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing

Jenna is a historian of science. Her research and teaching in Harvard's Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine. Currently, she's turning her dissertation into a book about "extralaboratory life," or how 19th century gender norms in everyday life outside the laboratory influenced the construction of biology as a discipline. @JennaTonn and http://scholar.harvard.edu/jennatonn