By Kathleen Sheppard

Countless people have been introduced to Egyptological fieldwork through the writings of Elizabeth Peters in her 19-volume Amelia Peabody Egyptology mystery series. Following Peabody, her husband Radcliffe Emerson, and their entourage around Egypt is dramatic, full of mystery, danger, fabulous finds, and, of course, romance.

Figure 1. Current cover of Crocodile on the Sandbank, originally published in 1975.

The Peabody-Emersons have a cult following; their fans are legion and devout. In fact, they are such earnest devotees that I hope I do not insult anyone by referring to Amelia Peabody in the past tense. I assure you: I do so for a purpose.

It has long been known that the fictional Peabody was an amalgam of a number of real women, most specifically, Amelia Edwards and Hilda Petrie. However, as I will show here, she was also based on the American traveler Emma Andrews, a globe-trotting Egyptologist whose life most directly mirrors Peabody's. By understanding more about Andrews’s life and work, we can more fully understand Peabody the character and Andrews the historical actor.

Elizabeth Peters, whose real name was Barbara Mertz, was an Egyptologist who got her PhD from the University of Chicago. She published in academia, but she is most famous for the Amelia Peabody series, which she wrote to entertain as well as to educate. Throughout the series, as Peters guided readers through each of the Peabody-Emersons’ excavation seasons in Egypt, she put real archaeologists and real sites into the stories as well, thus, mixing historical people with Victorian gothic fiction. She accurately introduced the scholarly activities of historical archaeologists using the fictional Peabody and Emerson as the narrators. In doing so, she inserted the Peabody-Emersons into a fictionalized but historical narrative.

For this to be believable she based her main characters on real historical actors. Men were all over the field in the late 19th century, but for Peters to put a woman like Amelia Peabody in the field required going against 19th century gender expectations for women. These expectations were embodied in a caricature of an ideal woman, the “Angel in the House,” and included attributes that Peabody actively worked against, such as being physically weak, meek, and submissive to her husband. Peabody exists as an idealized, 19th-century-yet-modern character, and a character, most importantly, based on a whole host of British women working in the field in Egypt. Who were these real archaeologists whose traits show up in Amelia Peabody?

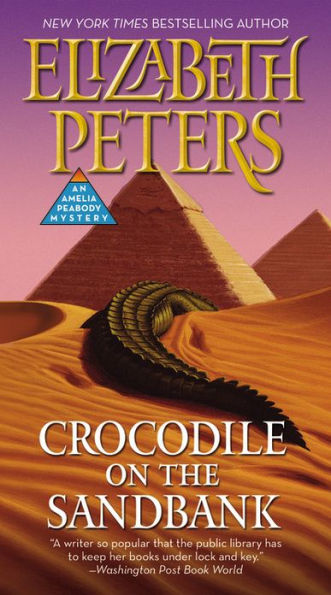

There are numerous fan blogs, tumblr sites, twitter feeds, and fan fiction that talk about some of the real people who make an appearance in the Peabody series. There has been at least one article devoted to the issue of real archaeologists in the series in the Egyptology journal KMT in 1990. The author argued that Amelia Edwards and Hilda Petrie were the main inspirations for Amelia Peabody. Edwards was the namesake for Peabody, and Petrie was the physical representation of her.

Figure 2. Hilda Petrie, courtesy TrowelBlazers.

However, as closely as we can trace the similarities of Edwards and Petrie to Peabody’s character, she was in fact an amalgam of women who worked in the field during the height of the Golden Age of Egyptology (1881-1914). Peabody was also Kate (Bradbury) Griffith, a wealthy Egyptologist who was also wife to a poor Egyptologist and who gave money so her husband could continue his work. She was the diminutive Margaret Murray, a snarky but well-liked Egyptologist, linguist, suffragette, and scholar who regularly acted, much like Emerson described Peabody, “as if she were seven feet tall instead of barely five.” (1)

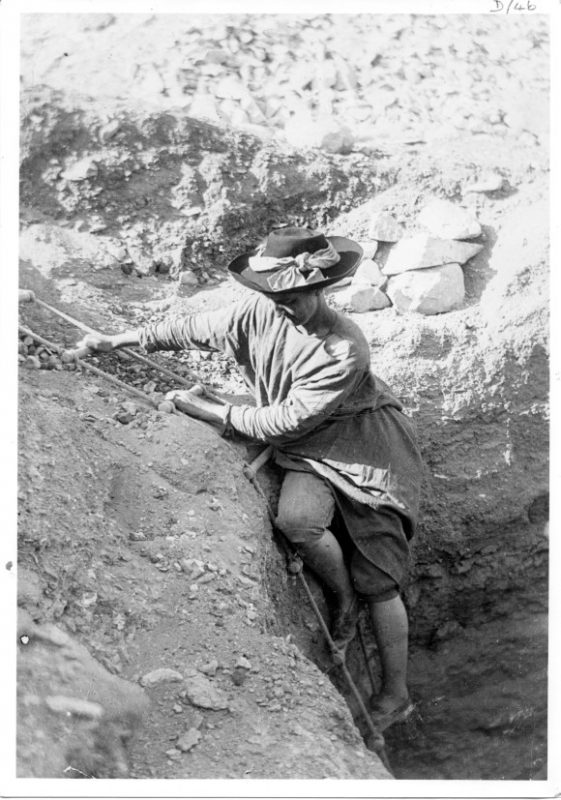

Despite the similarities to various women, I argue that we can see the fictional Peabody's attributes most fully in the American Emma Andrews (1837-1922), whose life and activities best reflect Peabody. Peters would have known of Andrews due to her Egyptological background. Andrews was an independently wealthy widow who became the traveling companion to robber baron Theodore Davis, who I have written about her briefly here. Andrews is known to us now largely because of her meticulously-kept diaries, copies of which remain at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. She was at the center of a massive network of wealthy men, site foremen, archaeologists, and diggers. Andrews and Davis traveled through Egypt for 25 years on their dahabeyah, The Bedawin, excavating and entertaining in equal measure. She had a lot of money and time — essential resources if you were going to do to archaeology in Egypt in the late-19th century.

Andrews' work, which consisted of keeping detailed lists of tomb finds, were the primary records for documenting the 20 tombs Davis found. She also maintained correspondence for Davis, took care of his nieces and other relatives when they were visiting, and ensured that the Bedawin was a welcoming place for visitors. One of the best examples of her archaeological contributions was the discovery of what is now known as KV 55, which was likely a cache of burial equipment from the Amarna royal necropolis. It is almost certain that the mummy was that of Akhenaten, an 18th dynasty king who had reshaped Egypt’s religion for a short period.

In 1907, Davis’s archaeologists Edward Ayrton and Arthur Weigall, found the entrance to a new tomb in the Valley. Andrews recorded the find in her diary and kept a strict record of visitors, tomb contents, and artifacts in situ. Most importantly, as Davis’s biographer John Adams points out:

[Andrews] took the time to produce something none of the [other] archaeologists seem to have bothered with and Davis failed to include in his publication: a floor plan of the tomb mapping where the major artifacts had been located. Rough as it is, her plan has been of value to Egyptologists ever since. (2)

Emma Andrews, along with Amelia Edwards and Hildie Petrie, provided vivid and historically specific characteristics for the intelligent, independent, fictional Peabody. The most clear similarity was that these women were, in and of themselves, field archaeologists.They contended with masculine partners and masculine field sites, and they prevailed — if only for a short time. Amelia Peabody-Emerson was a composite portrait of women in the field, and, in creating her as such, Peters presented a modernized version of the lady Egyptologist. Like all good historical fiction, and part of the reason fans love Peabody, the series prompts readers to learn more about the little-known women on which Peabody is based. While Edwards and Petrie are well known to readers and historians, the under-recognized Andrews arguably reflects more of Peabody, whose documentation practices were central to Egyptological discoveries, both then and now.

Notes:

1 Elizabeth Peters and Kristen Whitbread, Amelia Peabody’s Egypt: A Compendium (New York: William Morrow, 2003), 16.

2 John M. Adams, The Millionaire and the Mummies: Theodore Davis’s Gilded Age in the Valley of the Kings (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013), 146.

Further reading

Any of the books from the Amelia Peabody Series, starting with:

Elizabeth Peters, The Crocodile on the Sandbank, New York: Dodd, Mead, 1975.

Emma Andrews’ Diaries, in process of being transcribed and published by Sarah Ketchley at the University of Washington.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.