"To 'blow one's mind' means to become more aware."

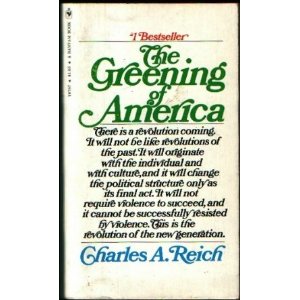

Charles Reich's 1970 defense of youth culture illustrates the problems with the politics of self-liberation.

To prepare for the New Inquiry's upcoming screening of 1968 teen exploitation film Wild in the Streets, I have been reading The Greening of America, a 1970 book by Yale law professor Charles Reich that sought to explain the righteous ways of teenagers to the rest of society. Reich actually mentions the film in a chapter about how the "Corporate State itself is generating rebellion," calling Wild in the Streets "truly subversive." In Wild in the Streets, teenagers secure the right to vote, vote themselves into power, and have all adults imprisoned in camps where they are kept high on LSD until they die. In The Greening of America, Reich explains how most Americans are trapped in Consciousness II — his jargon for the organization-man mentality, for the technocatic meritocratic Corporate system that made everyone into uptight, status-seeking drones with no "real"… Read More...