“I loved that book, Invisible Man, but the title says it all. It says, invisible to whom? Not to me.” – Toni Morrison in a Studio 360 interview with Hilton Als

“Even though Daughters have their own agenda with reference to this order of Fathers (imagining for the moment that Moynihan's fiction—and others like it—does not represent an adequate one and that there is, once we dis-cover him, a Father here), my contention that these social and cultural subjects make doubles, unstable in their respective identities, in effect transports us to a common historical ground, the socio-political order of the New World.” – Hortense Spillers, “Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book”

It’s probably been twelve years since my father left, left me fatherless

And I just used to say I hate him in dishonest jest

When honestly I miss this nigga, like when I was six

And every time I got the chance to say it I would swallow it – Earl Sweatshirt, “Chum”“We’re all aware of what’s going on here, aren’t we, baby?” – Dick Gregory, Nigger

I first read Dick Gregory’s Nigger years ago. I was a teen and had found the 1969 edition, withdrawn from the North York Public Library in Toronto in a pile of other free books. I was in Canada, which at 14 felt like the most frustrating place to be a black girl, and I was curious about what a word like “nigger” might mean for me.

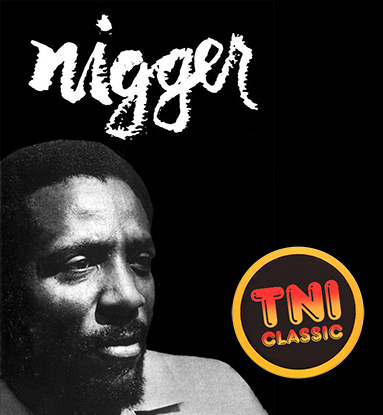

Since then, I’ve used Nigger most blatantly as an art commodity. Like the proud white girls who read Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick on the subway with their gripped hands in the air, I read Nigger on the streets, mostly park benches, where I didn’t feel (as) trapped. When I moved into a new apartment, in one of my first décor decisions, I propped Nigger up on the window ledge. It has the most beautiful cover: on an all-white background and in a disappearing black paintbrush cursive is that word, "nigger," all in lower-case. Once I opened and reread it, once I was really in it, that superficial kind of beauty stops. What remains is the kind of beauty that implicates you, asks you why you’re looking. I still don’t know for sure; I stare because of something like a mix of dread and desire, laughter and longing. It’s a serious book chronicling serious stuff (what it’s like to be poor and black) but it’s singed with a level of comedy that often makes the passages of, say, Gregory’s mother getting beat with a belt harder to swallow.

But if, as Gregory said to Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah in her 2013 essay “If He Hollers Let Him Go” for The Believer, “Comedy can’t be no damn weapon. Comedy is just disappointment within a friendly relation,” Gregory—the Gregory character we get to know through text at least—knows what true might is, what true violence.

***

Dick Gregory has said that Nigger was written in a way that white people would understand, which is one way to explain that it was written with sports journalist Robert Lipsyte. The autobiography chronicles Gregory growing up poor in segregated St. Louis, Missouri, his track-and-field career in high school and then at Southern Illinois University where he doesn’t graduate, his rise as an entertainer, and his civil rights activism.

Nigger was published in 1964, a year before the Moynihan Report, the U.S. Department of Labor’s publication also known as The Negro Family: The Case for National Action—and now somewhat of a black studies anti-bible. Hortense Spillers, wrote about it better than anyone ever could, in her 1987 "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” She writes that in the Moynihan Report, “the ‘Negro Family’ has no Father to speak of—his Name, his Law, his Symbolic function mark the impressive missing agencies in the essential life of the black community, the ‘Report’ maintains, and it is, surprisingly, the fault of the Daughter, or the female line. This stunning reversal of the castration thematic, displacing the Name and the Law of the Father to the territory of the Mother and Daughter, becomes an aspect of the African-American female's misnaming.”

Following that mid-'60s moment of policy visibility, Nigger, then, could be said to be a book about the Fatherless Negro Family, or at least one version of its fiction. Nigger, which sold millions of copies while Gregory was a successful (and funny) comedian and a civil rights activist, is not a social etymology of a “controversial” word, a marking of the borders of the limits of the sayable. Although, it’s true, when Ghansah wrote that “One also cannot discuss the n-word without discussing Dick Gregory.” In other words, one cannot discuss the word “nigger” without discussing the social relations that bind us. What can’t be said is never just a word, never “nigger” only. Ten years ago, I read Nigger looking for a kind of black practice of life, politics, love. I would have then guilelessly called it “community.” I am now unsatisfied with the recognition and acknowledgement a word like community, when pseudo-institutionalized, implies. Ten years ago, I brought Nigger with me to Jamaica to read on the beach while my dad was at work. He was always at work when I was visiting him where he lives on the Western part of the island in a small tourist town. My first few readings focused on the male characters, Dick Gregory and his father, and culled them into representative figures in order to make sense of my own #daddyissues.

Similar to what Toni Morrison said of Invisible Man, the title “nigger” doesn’t attend to the sociality that happens beyond the label of “social problem,” the sociality around all the shitty sugar-loaded dinners (Twinkies and Pepsis)—and that’s despite the complex role comedy plays. It seems as though Gregory’s main concern is to not be called nigger, to be addressed with respect in a state that wants to kill him and has, we later learn, killed his mother.

One of the most quoted one-liners is the ironic dedication, which frames the book: “Dear Momma—Wherever you are, if you ever hear the word ‘nigger’ again, remember they are advertising my book.” While there is so much in this book addressed to her, Gregory’s claim to Americanness is siphoned through the memory and image of his suffering and destitute mother, and as a result, that claim is validated. If, as Angela Davis wrote in 1971, “the matriarchal black woman has been repeatedly invoked as one of the fatal by-products of slavery,” then the address and regard for the lost black mother does a particular kind of work, one of mining investments and attachments. What kind of work is the black woman expected to do perhaps only because of the now rather exhausted mother/son binary relationship?

***

Today I read Nigger more like a séance with my own nigger-ness, which is to say, a claim on our own nigger-ness. Today I read Nigger after a few years of a particularly fraught relationship with my own dad. Today I read Nigger looking for something devour.

When rereading, I mostly don't read books like this anymore, I thought, books so publicly filled with true stories and facts, narrativized autobiographies, books where thing after thing happens, books so concerned with a sequence of events. I don’t love to read books written by men—I do read them, a lot of them and even more with a masculine point of view—but I’d almost always rather be reading something written by a woman. Why be reminded that men exist?

And then in Nigger, there are moments like this where I’m reminded why I’m reading: "I started walking again, choking on the heat and the dust, watching my blood run down the sidewalk and the insides come out of my hand. It was white. Then I fainted. A wonderful feeling, like falling away from the world." Or like this, Gregory’s description of the summer before the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham in 1963: “It was like being in the forest in the daytime when the sun is shining and everybody’s having picnics and laughing and playing ball, and then suddenly it’s night and you’re alone. You’re running through the pitch-black cold.”

In moments like these, recalling to me a kind of enabling écriture, there is no holding back. Nigger lends itself to a kind of indeterminacy, a kind of sangfroid, where I read not for content but for gaps and silences. That being said, the part where I feel the gulf between my self and my blood is the first 60 or so pages. I take Dick, the child, seriously. Once Dick grows up, I feel less and less like him. And I like his character less and less. He becomes a man. I stay a woman.

In reading, then, I gravitate to the first sustained yet very faint presence of a woman, Gregory’s Momma, who is also the prototype of black womanhood. She works as a maid in white people’s homes. The first of several documentary-style photographs in the book is of her (a “her” who I have not yet named till…now), immortalized with the caption “Lucille Gregory (‘Momma’) 1904-1953.” In the black-and-white image, Momma lifts her eyes and looks to the heavens with a bright gap-toothed smile. Momma is sitting for a studio portrait photo, all cheap lights and artifice, but she looks happy, however feigned and steeped in respectability politics, and I get now why Gregory compares her to Miss America. And means it.

Despite the presence of some image of her real self, I don’t gravitate to her because she offers a redemptive “Dear Mama” narrative but because of the ways depression and dispossession enact itself on her character. The black maternal figure, as we know, props up and reflects the heroic ones who persevere. But in her drama, her forever-impending death, she also nervously reflects the future: the daughter, then the girlfriend, then the wife.

***

Lucille, however discredited, destabilizes me. I guess I am a daughter and also sometimes a girlfriend and I gravitate to Momma because she waits. She is constantly waiting. She’s waiting for regulatory regimes to act. She’s waiting for love. She’s waiting for welfare, she’s waiting for her check from work. She’s waiting on her dirty-ass kids. Most of all she’s waiting for Gregory’s father to come home, even in her own death it feels like she’s waiting.

Momma’s helplessness reflected the wretchedness I felt being compelled to wait for someone so far away—mentally and physically. My dad moved to Canada from Jamaica in the 1970s after his grandmother sent for him when she moved a few years prior as a nurse’s assistant. Before I started kindergarten, he moved back. I saw him maximum once a year since.

I waited for my dad for years. I waited for him to remember my birthday. I waited for him to pick me up at the airport in Montego Bay. I waited wearing the sneakers he bought me. Even when I entered adulthood and committed to something like the Nicki Minajism of “I don’t wait on niggas,” I knew that sometimes I would feel forced to.

In reading Nigger, it felt like capital H Hate to despise a black father trying to get by in a world structured to kill him. After all, he left Toronto because he didn’t want to compromise. He had been the oldest brother to migrate. He aspired to be the big boss—and in Canada in the 1990s, where he drove trucks, a black man was only ever allowed to be the most basic kind of boss. His desire for middle-class ownership eventually came true: he built a house of his own and he’s what they call in North America an entrepreneur.

I wanted to hate him, call a black father a dick and mean it. How is it possible to yell and scream—to elucidate my position in the world—articulated in the realm of “the struggle” where there are sides and we’re supposed to be on the same one?

***

In The Lover’s Discourse, Roland Barthes famously wrote that “the lover’s fatal identity is precisely: I am the one who waits.” There is no real thing being waited for, no outside to not waiting except, maybe, scale or social position. In that oceanic space of waiting, what does Momma do? She works, she makes Christmas dinner, she listens to her children, she navigates the social worker, she cries. Waiting is never only a passive act, a receptacle for things happening and the world fast-forwarding outside of a window. Perhaps the idea of waiting, then, adds a kind of formality, makes the object worth the wait.

In 1953 at the age of 49, Lucille Gregory dies while in Dick is in his senior year at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois. His track coach tells him to phone home and right away, without as much as a clue, he asks, “Is it Momma?” He knows her closeness to death. He blames himself but he knows that America killed Momma.

Momma is everyone and no one, something like a meaningless yet essential pop refrain, always repeated throughout the pages of Nigger. Daddy, also known in their St. Louis neighborhood as Big Pres (after Presley), is a quite literal blow, something jolting yet something profoundly serious. In the book, though, Daddy is again leaving after he has come back. That is the heterosexual vision of flux. Nothing stays.

As Dick Gregory is the second of six children, these Daddy scenes in Nigger are brief and front-loaded, and evoke a cacophony of children screaming and the sound of kicking. While Daddy is always disappearing, always disintegrating, even in front of your eyes, he’s ever more present. Gregory clings onto the bullshit, makes it comedic gold in the way that we understand American comedy as defense, or is it last resort? “I got picked on a lot around the neighborhood; skinniest kid on the block, the poorest, the one without a Daddy,” he writes. “I guess that’s when I first began to learn about humor, the power of a joke.”

From the bottom to the top of the world—the top obviously being Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club—Big Pres finally reappears like a footnote after leaving his family for years. “We didn’t talk very long,” Gregory writes, “There wasn’t very much to say.” Even though they’re not talking, it doesn’t matter, because the men do and, most importantly, are being seen doing. At least in how we look back at that time, the fiction of a strong black leader was potent, constructing actors, not those who get acted on, those who wait for change. You don’t wait, says America, you get out and get yours.

***

At the end of the book, when Dick Gregory has three children, he loses his son to pneumonia. His name is Richard Junior. Gregory is left to explain to his kids where Richard Junior went:

“Michele, honey, where’s Richard?”

“Richard’s gone, Daddy.”

“Gone where?”

“To the hospital.”

“When will he be back?”

“He’s not coming back, Daddy. You’ll have to get another Richard.”

“How do you know?”

“I looked at Mommy’s face.”

The kids see Mommy’s face all the time, with such clarity, with such softness, with such care. I don’t dare ask “Who else sees Mommy?”

Gregory now makes Mommy, his wife Lillian who just lost her kid, make the decision: between Richard Junior or Richard. In her grieving, Gregory writes, “I knelt there and I looked at a woman’s face that was so distorted it wasn’t even human, a face with two holes for eyes that were filled with hate for me. She jerked and twisted and I jumped up and pinned her down on the bed and I screamed at her.” Lillian chooses Richard Junior. She doesn’t make Gregory’s mother’s mistake.

Later, instead of a non-human vision, after his wife Lillian had been jailed for a SNCC-organized voter registration drive in Selma, she’s the most human vision:

I’m driving with tears in my eyes. Here’s a woman who just spent eight days in jail, and she’s able to sit back there, so patient and kind, and tell her kids about the different kinds of gasoline. I wish I had that kind of beauty. I wish the world was that free from malice and hate.

Whatever her name, Mommy or Momma, the different suffixes mark the figure as similarly fungible. She’s at once pathetic, paralyzed and disgusting, signaled by her waiting and especially by her waiting for a cheater, a no-good, and also some light vision of universal progress, both the degrader and carrier of culture. In an atmosphere of catastrophe, maternal loss and the memorials loss produces structure a moving forward because god forbid a man suffer and not do anything about it. Gregory writes in his coda: “You didn’t die a slave for nothing, Momma.” In death, she is once again flesh.

Like the dedication, the last chapter in Nigger is a moving address to Momma and “all those Negro mothers who gave their kids the strength to go on.” Dick Gregory is a player in the revolution. Part of what makes Gregory a nigger is his stamp of fatherlessness, making his mother’s degradation that much more pronounced. The black woman’s “strength,” it turns out, is fairly criminal. Momma’s absence, either a psychic one during her life or a more material one in her death, creates a pace for Gregory’s impetus toward social change.

Dick Gregory is finally an American; Momma died over a hundred pages ago.