Wayne’s prison memoir is one of the most boring ever written, which is why it’s a success

“THE Price Is Right was on in the dayroom. I tried to play along, but just kept thinking about how this place is wrong.”

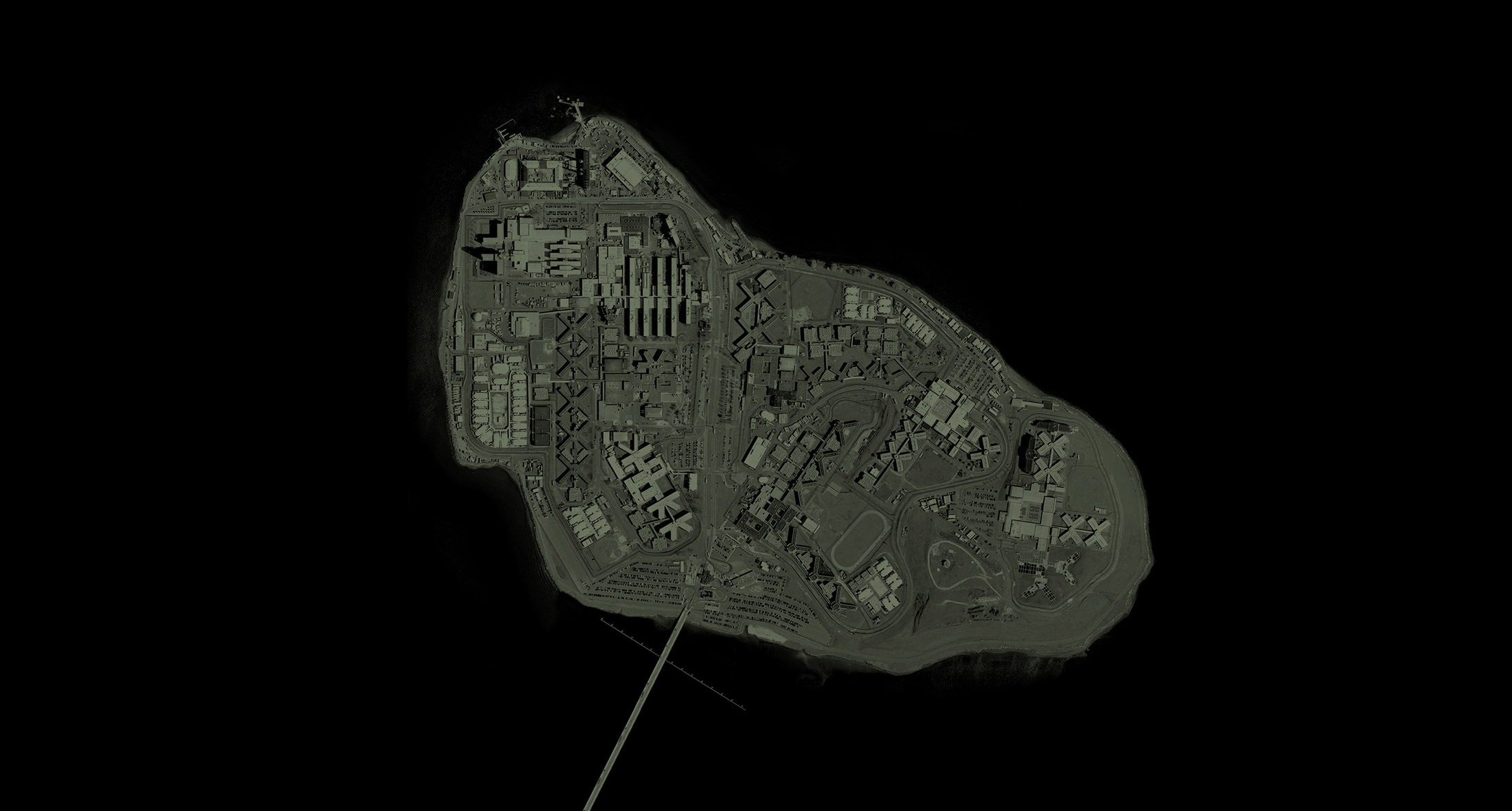

Lil Wayne’s Gone ‘Til November is, in all likelihood, a faithful, if slightly amended, reproduction of Weezy’s actual diary from the eight months in 2010 that he spent at the Eric M. Taylor Center (EMTC) at Rikers Island, home to sentenced inmates serving one year or less. It is designed to resemble a composition notebook, inside and out, right down to its faux-handwritten font. Inside, Weezy’s writing is stream of consciousness, unvarnished, and primarily focused on the banalities of daily life at EMTC, widely regarded as the calmest facility at Rikers. Despite his celebrity and the recent attention being paid to the island prison, Lil Wayne’s account of his incarceration has drawn remarkably little notice, and it’s not his fault: He has simply captured daily life at EMTC in a way that doesn’t fit with the splashy headlines of Rikers’s corruption and violence. Still, his account represents the facility just as damningly and faithfully.

“I got back up early enough to get a shave,” Weezy writes, “Yeah!” In fits of manic enthusiasm punctuated by melancholy (Yeah!” is a common rejoinder, as well as its opposite, “Damn!”), he documents the major events of each day: the triumphs of waking up early, often before dawn, for the coveted packets of sugar that come with breakfast, and a bit later for access to a tightly controlled razor for shaving; “being able to escape the harshness of jail” through visits but dreading the accompanying strip-searches where the COs tell you to squat and “lift up ya nutsack!”; scoring a two-piece uniform, a cherished Rikers commodity to replace his one-piece jumpsuit; chatting with the male COs about sports and flirting with the women; and being exasperated with how everyone in jail would “yell regular conversations at the top of their lungs and say everything twice: ‘Eh yo, them niggas down there be buggin’... them niggas be buggin’! That’s my word, that’s my word, son!’” He wonders, “I don’t know if it’s a jailhouse thing, New York thing, or a New York jailhouse thing, but it’s for damn sure an annoying-as-fuck thing!”

Weezy’s entries end with nightly rituals of communal commissary meals

Otherwise, Weezy lounges in the dayroom watching American Idol, Undercover Boss, and on “DVD day” (a cherished privilege), a Martin marathon. He plays his hand in the informal economy: “I traded a coffee pack for a pack of noodles. Damn… I’m really in jail!” He briefly tries his hand at a job, suicide prevention aid, Rikers’s highest paid position--over $100 dollars each week, an additional $50 dollars if you stop someone from hanging themselves, or $25 dollars if you find them dead--before tiring of the night shift, where he can only really chat with whoever is awake. Weezy writes letters, argues and reconciles with his various lady friends, and surprises a few lucky fans with phone calls. Unlike most of his fellow inmates, he gets regular visits, a torrent of mail, and even some unsolicited business offers: “Received a movie script… Damn and Yeah! First the ‘yeah’... It was a script for New Jack City 2, and I was to play the son of mothafuckin’ Nino Brown! Now the ‘damn’... They only sent it to me in hopes I’d fund the project.”

There’s a little bit of action here and there. Wayne and the boys play a trick on their friend Dominicano by setting up an elaborate wedding with Coach as the willing bride, and later, Wayne is punished for having an MP3 player in his cell, and after a confrontation with a high-ranking officer, flanked by 20 goons, in the shower, Wayne is sentenced to 30 days in solitary confinement--an increasingly common practice at Rikers since the early 1990s for minor disciplinary infractions such as possession of harmless contraband. In fact, this practice--widely considered a form of torture and recently eliminated for detainees and inmates under 21, following a concerted activism campaign--is deployed so frequently that Wayne is put on a waiting list.

For the most part, this book could take its title from one of Wayne’s entries, “Days spent doing too much of fucking nothing,” when Wayne and his friends are locked in their cellblock for almost the entire day and with nothing to do. This is not just because they’re in protective custody--boredom is the policy at EMTC. EMTC has no library, except for a “Law Library” staffed by inmate-workers who don’t know anything about the law, and where an equally ignorant CO monitors inmates’ work to ensure it pertains to a legal appeal, ejecting them after an hour. Inmates are offered an hour to stand around in the yard each day, often when many are out getting medicine or methadone, in which case their hour is up until tomorrow. The same goes for medical care of any kind. Inmates sign up on a list for the following day and may or may not be called. Inmates requesting emergency services are accused of faking and told to wait.

Deprived of anything to do except work menial jobs--which are in limited supply, especially for the short-term inmates who make up the bulk of the EMTC population

Weezy, of course, enjoys privileges and pitfalls in accordance with his status as Rikers’s most famous inmate: He learns a nurse only began wearing makeup when he showed up, other inmates kiss his ass, and he’s apologetically told he’s being sent to the box so the Department of Corrections can save face when the story of his MP3 player leaks. But to dismiss his experience as an outlier would be a mistake because his account of it illuminates many common elements of life at EMTC. While it was certainly not built for the rich and famous, reading Weezy’s jailhouse experiences as exemplary of how and why the institution functions can shed some light on why, despite the author’s best intentions and skill at capturing the poetry of the banal, his book is so unbelievably goddamned boring.

THE Eric M. Taylor Center (EMTC), the Rikers Island facility also known as building C-76, opened in 1964 as the New York City Corrections Reception and Classification Center. The Center was conceived as a humane alternative to the decrepit and purely punitive conditions of incarceration at nearby Hart Island. The latter, in its rich history, has hosted a Foucauldian smorgasbord of institutionalized subjects--juvenile delinquents, psychiatric patients, inveterate alcoholics, disobedient sailors, incapacitated senior citizens, the homeless, and convicted prisoners serving short sentences--all in a gloomy and decrepit penal colony revolving around New York City’s burial ground for unclaimed bodies and amputated limbs, still operating to this day. With Hart Island as a foil, the Classification Center was based on a model for prisoner rehabilitation championed by Corrections commissioner Anna Moscowitz Kross, a former judge and distinguished criminal justice reformer, suffragist, and one-time labor lawyer. In Kross’s design, the center would provide intensive evaluation of all inmates coming into the New York Department of Correction system by using clinicians and social workers to craft plans for rehabilitation tailored to each inmate in days jam-packed with activities and programs meant to put the inmates on the right track to re-enter society.

In 1965, Kross wrote:

Although the present Reception & Classification Center building was originally planned to replace the old traditional workhouse, our growing understanding of the mechanics of true correction and of the need for something far beyond the haphazard work assignments of time-worn practices led us to our present short-term pioneering effort. A new phase of our Rehabilitation Program is being undertaken there.

When Mayor John Lindsay dedicated the bridge connecting Rikers Island to mainland Queens, the mile-long span was effusively dubbed the Bridge of Hope. Today the crumbling stretch is known as the Bridge of Pain.

While there is evidence that Kross may have in fact pioneered a method of intensive rehabilitation at C-76, it can only be speculated whether her experiment would have succeeded in the long term. What we do know is that in the face of nascent neoliberalism, deindustrialization, and the rise of “law and order” policing--the ingredients of what would become mass incarceration--Kross’s dream didn’t stand a chance.

Already in 1968, as a bellwether of changes to come, C-76 had been renamed the New York City Corrections Center for Men. While retaining the practice of intake classification--which continues at an extremely reduced capacity to this day--it also began to function as a more traditional holding facility for inmates serving “city time” of one year or less, including housing juvenile offenders. Inmates are housed in dormitory-style units with upwards of 80 beds, and confined to these quarters for almost the entire day. Numerous lawsuits filed since the 1970s, journalistic exposes, and a stream of first-hand testimonials from formerly incarcerated people paint a picture of this facility as it has operated for the vast majority of its existence: as a place where just about anything can happen except, it seems, “rehabilitation.”

In 2000, C-76 was renamed again--this time after a former corrections chief, who got his start when he was laid off from the NYPD during the 1970s economic crisis and found that the New York City Department of Corrections was hiring. Alongside Norman Seabrook and Bernard Kerik, Eric M. Taylor introduced a program called the Total Efficiency Accountability Management System (TEAMS), a statistically driven corporate-management program in the style of NYPD’s CompStat. Taylor’s reforms are touted as dramatically reducing violence in the corrections system in the mid-1990s. However, these reforms also entailed the explosion in the punitive use of solitary confinement, like Wayne experienced, and increased restriction on inmate movement within the facility, which Wayne’s case typifies to the extreme.

This was all enforced by the growth of a “culture of violence” denounced in the previously mentioned Department of Justice report, which it claims is largely kept off the radar of official statistics by the widespread institutional practice of inmates being instructed to “hold it down,” or not report violence from COs or other inmates. To date, the only “progressive” program that can be found in most EMTC blocks is the Key Extended Entry Program (KEEP), which keeps inmates zonked out on high dosages of methadone all day, as an alternative to intensive drug treatment.

But even more pervasive than the violence, which rightfully grabs headlines and dominates the lion’s share of prison reform rhetoric, is the enforced immobility, combined with the withdrawal of programs and services, that produce endless days in which there is quite literally nothing for most inmates to do but sit around. There is no effort at rehabilitation of any kind. The COs refer to inmates as “bodies” and “packages,” and treat them as inanimate objects to be transported, with minor requirements for upkeep such as regular meals. On its face, this may seem like a grave mistake, as many prison reformers are wont to argue, pointing to humane programs in the Netherlands as alternatives. It is commonly said that people are locked up out of hatred or other strong emotions. But this misunderstands the dispassionate banality of mass incarceration.

Most people who find themselves in a place like EMTC are not locked up in order to make them better citizens, capable of reintegration into gainful employment. On the contrary, they are locked up because there is nowhere else to put them. Addiction, mental illness, homelessness, and chronic unemployment account for a vast majority of the inmate population. For the lowest (and highly racialized) rungs of the labor market, there is little work, little housing, and put bluntly, little space for them in the current economy. The U.S. ruling class has no interest in income redistribution through social welfare policies; these were rejected the 1970s in in favor of what’s known as the carceral state.

Accordingly, the only public sector unions with substantive political power are prison guards and police officers, and these forces receive the lion’s share of funding to deal with issues such as unemployment, mental health, drug abuse, and homelessness, which are directly related to the neoliberal disinvestment from social services that were inadequate in the first place. Thus, in the case of EMTC, a facility that was envisioned as a humane alternative to the brutish workhouse of Hart’s Island has itself become a brutish place where daily life is so degraded that work is coveted above all other activities. The inmate is bored because there is no need for the inmate to be anything but bored.

The beauty of Gone ‘Til November is that it captures not only the crushing debasement of human life but also the perverse flowering of the human spirit in such an intellectually, materially, and spiritually impoverished setting. Friendships bloom, laughter echoes throughout the blocks, and flashes of joy, triumph, and sentimentality momentarily remove the inmate from the reality of a debasing institution. A multimillionaire, Weezy quickly finds himself rejoicing over iced Gatorade, makeshift meals seasoned with crushed up Doritos, adding extra sugar to the cereal he eats out of a recycled peanut butter jar, and listening to slow jams on a low quality radio.

But more striking than the material comforts are the social ties Wayne forges: the goofy jokes, the transmission of local knowledges like recipes, tricks of the trade, and general survival skills in pithy adages. In the conditions at EMTC, camaraderie blooms alongside conflict, and intense bonds are formed, though they are rooted more in proximity than in anything more enduring. “I pray for everybody in here,” Wayne admits, “but I don’t really see myself keeping in touch with anybody but a couple of COs who never acted like dicks toward me.”

As the campaign to close Rikers Island gains momentum as more people realize that this rotting avatar of mass incarceration cannot be reformed, it is necessary to argue that even the boredom at Rikers is indefensible. Lil Wayne’s most boring days are tied to the most violent days at Rikers: They are interrelated symptoms of a larger social ill which must be eradicated in all its parts. Far from a minor side effect of incarceration, boredom and the sheer futility of life behind bars is a key element of the prison experience that often takes backseat to sensationalist stories. In terms of explanatory power, the acute boredom communicates the impersonality and dispassionateness of mass incarceration far more accurately than the tales of impassioned violence. In short: You are not locked up because society cares so much about you that they want to hurt you, stem your advancement, or assert supremacy over you. You are locked up because nobody with any social power cares about you enough to make it stop or to give you a better life.

This is where boredom in prison becomes political. It is often argued that it would be futile to close a place like Rikers while changing nothing else about our society, which has little to offer the people who would suddenly be free. But this is not a cause for defeatism; instead, it is a reminder that the struggle for prison abolition must be done with a broader eye to the social conditions that make boredom at Rikers necessary: namely, the concentration of private property in an ever-shrinking set of hands. To end incarceration as it is practiced at Rikers and to begin to end incarceration as we know it requires a corresponding movement to redistribute wealth and social power throughout our society. It demands the end of the existence of a class of people who just sit around all day and rot.