Reports of a general “death taboo” have been greatly exaggerated

Afternoon with Michel, sorting maman’s belongings.

Began the day by looking at her photographs.

A cruel mourning begins again (but had never ended).

To begin again without resting. Sisyphus.

—Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary

“Secure the Shadow, ‘Ere the Substance Fade

Let Nature imitate what Nature made”

—19th century daguerrotype advertisement

A grimacing teenager in a striped shirt stands with his back to an open casket. A caption accompanies the image: “MY FRIEND TOOK A SELFIE AT A FUNERAL AND DIDNT REALIZE HIS DEAD GRANDMA WAS IN THE BACKGROUND I CANT BREATHE.” Both photograph and caption were reproduced without comment by Jason Feifer on a short-lived Tumblr named Selfies at Funerals, a collection of similar photos in which young women primp in black dresses, lips in duck-face formation, or young men cheerfully pose with portraits of newly deceased grandparents.

The apparent message of Selfies at Funerals was clear: Young people’s need to endlessly photograph themselves and overshare now extends to a cavalier disrespect for the dead. In an essay for Flavorwire, Tyler Coates attempted to defend teens, arguing that what Selfies at Funerals actually reveals is adults’ desire to make fun of teenagers. He notes the “underlying narcissism on display in [adults’] performance of grief” with respect to late celebrities like Lou Reed, but doesn’t dispute the idea that public grieving is inherently narcissistic. The reaction to funeral selfies — as with the recent debates about illness tweets, which some critics equated with them — sheds light not on the generational divide so much as our discomfort with social media and death, especially where they overlap.

If love, sex, and even sleep are caught up in the network society, then death is also similarly embroiled. In the case of funeral selfies, photographs of young, attractive and well-dressed teenagers act as an antidote to death but also serve as a reminder of mortality. After all, these same teenagers may come across the memorialized profiles of dead friends on Facebook or have photographs of dead loved ones on Instagram, replete with snazzy filters. As more people go online, impromptu and unintentional memorials arise and dead people’s accounts become virtual shrines and spaces for collective grief.

By Facebook’s 10th anniversary in February 2014, the site claimed well over a billion active users. Embedded among those active accounts, however, are the profiles of the dead: nearly anyone with a Facebook account catches glimpses of digital ghosts, as dead friends’ accounts flicker past in the News Feed. As users of social media age, it is inevitable that interacting with the dead will become part of our everyday mediated encounters. Some estimates claim that 30 million Facebook profiles belong to dead users, at times making it hard to distinguish between the living and the dead online. While some profiles have been “memorialized,” meaning that they are essentially frozen in time and only searchable to Facebook friends, other accounts continue on as before.

In an infamous Canadian case, a young woman’s obituary photograph later appeared in a dating website’s advertising on Facebook. Her parents were rightly horrified by this breach of privacy, particularly because her suicide was prompted by cyberbullying following a gang rape. But digital images, once we put them out into the world on social networking platforms (or just on iPhones, as recent findings about the NSA make clear), are open to circulation, reproduction, and alteration. Digital images’ meanings can change just as easily as Snapchat photographs appear and fade. This seems less objectionable when the images being shared are of yesterday’s craft cocktail, but having images of funerals and corpses escape our control seems unpalatable.

While images of death and destruction routinely bombard us on 24-hour cable news networks, images of death may make us uncomfortable when they emerge from the private sphere, or are generated for semi-public viewing on social networking websites. As I check my Twitter feed while writing this essay, a gruesome image of a 3-year-old Palestinian girl murdered by Israeli troops has well over a thousand retweets, indicating that squeamishness about death does not extend to international news events. By contrast, when a mother of four posted photographs of her body post cancer treatments, mastectomy scars fully visible, she purportedly lost over one hundred of her Facebook friends who were put off by this display. To place carefully chosen images and text on a Facebook memorial page is one thing, but to post photographs of a deceased friend in her coffin or on her deathbed is quite another. For social media users accustomed to seeing stylized profiles, images of decay cut through the illusion of curation.

In a 2009 letter to the British Medical Journal a doctor commented on a man using a mobile phone to photograph a newly dead family member, pointing out with apparent distaste that Victorian postmortem portraits “were not candid shots of an unprepared still warm body.” He wonders, “Is the comparatively covert and instant nature of the mobile phone camera allowing people to respond to stress in a way that comforts them, but society may deem unacceptable and morbid?” While the horrified doctor saw a major discrepancy between Victorian postmortem photographs and the one his patient’s family member took, Victorian images were not always pristine. Signs of decay, illness, or struggle are visible in many of the photographs. Sickness or the act of dying, too, was depicted in these photos, not unlike the practices of deathbed tweeting and illness blogging. Even famous writers and artists were photographed on their deathbeds.

Photography has always been connected to death, both in theory and practice. For Roland Barthes, the photograph is That-has-been. To take a photo of oneself, to pose and press a button, is to declare one’s thereness while simultaneously hinting at your eventual death. The photograph is always “literally an emanation of the referent” and a process of mortification, of turning a subject into an object — a dead thing. Susan Sontag claimed that all photographs are memento mori, while Eduardo Cadava said that all photographs are farewells.

The perceived creepiness of postmortem photography has to do with the uncanniness of ambiguity: Is the photographed subject alive or dead? Painted eyes and artificially rosy cheeks, lifelike positions, and other additions made postmortem subjects seem more asleep than dead. Because of its ability to materialize and capture, photography both mortifies and reanimates its subjects. Not just photography, but other container technologies like phonographs and inscription tools can induce the same effects. Digital technology is another incarnation of these processes, as social networking profiles, email accounts, and blogs become new means of concretizing and preserving affective bonds. Online profiles and digital photographs share with postmortem photographs this uncanny quality of blurring the boundaries between life and death, animate and inanimate, or permanence and ephemerality.

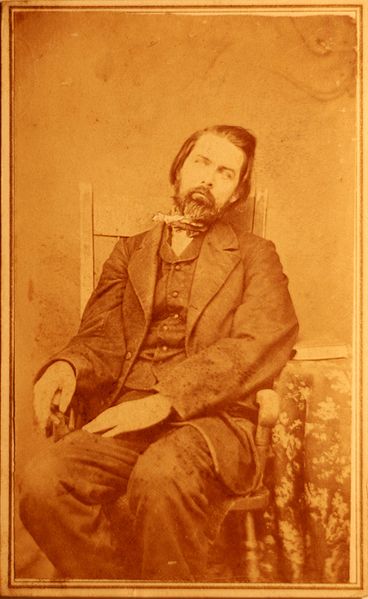

Sharing postmortem photos or mourning selfies on social media platforms may seem creepy, but death photos were not always politely confined to such depersonalized sources as mass media. Postmortem and mourning photography were once accepted or even expected forms of bereavement, not callously dismissed as TMI. Victorians circulated images of dead loved ones on cabinet cards or cartes de visite, even if they could not reach as wide a public audience as those who now post on Instagram and Twitter. Photography historian Geoffrey Batchen notes that postmortem and mourning images were “displayed in parlors or living rooms or as part of everyday attire, these objects occupied a liminal space between public and private. They were, in other words, meant to do their work over and over again, and to be seen by both intimates and strangers.”

Victorian postmortem photography captured dead bodies in a variety of positions, including sleeping, sitting in a chair, lying in a coffin, or even standing with loved ones. Thousands of postmortem and mourning images from the 19th and early 20th centuries persist in archives and private collections, some of them bearing a striking resemblance to present day images. The Thanatos Archive in Woodinville, Washington, contains thousands of mourning and postmortem images from the 19th century. In one Civil War-era mourning photograph, a beautiful young women in white looks at the camera, not dissimilar to the images of the coiffed young women on Selfies at Funerals. In another image, a young woman in black holds a handkerchief to her face, an almost exaggerated gesture of mourning that the comically excessive pouting found in many funeral selfies recalls. In an earlier daguerreotype, a young woman in black holds two portraits of presumably deceased men.

Batchen describes Victorian mourners as people who “wanted to be remembered as remembering.” Many posed while holding photographs of dead loved ones or standing next to their coffins. Photographs from the 19th century feature women dressed in ornate mourning clothes, staring solemnly at photographs of dead loved ones. The photograph and braided ornaments made from hair of the deceased acted as metonymic devices, connecting the mourner in a physical way to the absent loved one, while ornate mourning wear, ritual, and the addition of paint or collage elements to mourning photographs left material traces of loss and remembrance.

Because photographs were time-consuming and expensive to produce in the Victorian era, middle-class families reserved portraits for special events. With the high rate of childhood mortality, families often had only one chance to photograph their children: as memento mori. Childhood mortality rates in the United States, while still higher than many other industrialized nations, are now significantly lower, meaning that images of dead children are startling. For those who do lose children today, however, the service Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep produces postmortem and deathbed photographs of terminally ill children.

Memorial photography is no mere morbid remnant of a Victorian past. Through his ethnographic fieldwork in rural Pennsylvania, anthropologist Jay Ruby uncovered a surprising amount of postmortem photography practices in the contemporary U.S. Because of the stigma associated with postmortem photography, however, most of his informants expressed their desire to keep such photographs private or even secret. Even if these practices continue, they have moved underground. Unlike the arduous photographic process of the 19th century, which could require living subjects to sit disciplined by metal rods to keep them from blurring in the finished image, smartphones and digital photography allow images to be taken quickly or even surreptitiously. Rather than calling on a professional photographer’s cumbersome equipment, grieving family members can use their own devices to secure the shadows of dead loved ones. While wearing jewelry made of human hair is less acceptable now (though people do make their loved ones into cremation diamonds), we may instead use digital avenues to leave material traces of mourning.

Why did these practices disappear from public view? In the 19th century, mourning and death were part of everyday life but by the middle of the 20th century, outward signs of grief were considered pathological and most middle-class Americans shied away from earlier practices, as numerous funeral industry experts and theorists have argued. Once families washed and prepared their loved ones’ bodies for burial; now care of the dead has been outsourced to corporatized funeral homes.

This is partly a result of attempts to deal with the catastrophic losses of the First and Second World Wars, when proper bereavement included separating oneself from the dead. Influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis’s categorization of grief as pathological, psychologists from the 1920s through the 1950s associated prolonged grief with mental instability, advising mourners to “get over” loss. Also, with the advent of antibiotics and vaccines for once common childhood killers like polio, the visibility of death in everyday life lessened. The changing economy and beginnings of post-Fordism contributed to these changes as well, as care work and other forms of affective labor moved from the domicile to commercial enterprises. Jessica Mitford’s influential 1963 book, The American Way of Death, traces the movement of death care from homes to local funeral parlors to national franchises, showing how funeral directors take advantage of grieving families by selling exorbitant coffins and other death accoutrements. Secularization is also a contributing factor, as elaborate death rituals faded from public life. While death and grief reentered the public discourse in the 1960s and 1970s, the medicalization of death and growth of nursing homes and hospice centers meant that many individuals only saw dead people as prepared and embalmed corpses at wakes and open casket funerals.

Despite this, reports of a general “death taboo” have been greatly exaggerated. Memorial traces are actually everywhere, prompting American Studies scholar Erika Doss to dub this the age of "memorial mania." Various national traumas have led to numerous memorials, both online and physical, and likewise, on social media, including tactile examples like the AIDS memorial quilt, large physical structures like the 9/11 memorial, long-standing online entities like sites remembering Columbine, and more recent localized memorials dedicated to the dead on social networking websites.

But these types of memorials did not immediately normalize washing, burying, or photographing the body of a loved one. There's a disconnect between the shiny and seemingly disembodied memorials on social media platforms and the presence of the corpse, particularly one that has not been embalmed or prepared.

Some recent movements in the mortuary world call for acknowledgement of the body’s decay rather than relying on disembodied forms of memorialization and remembrance. Rather than outsourcing embalmment to a funeral home, proponents of green funerals from such organizations as the Order of the Good Death and the Death Salon call for direct engagement with the dead body, learning to care for and even bury dead loved ones at home. The Order of the Good Death advises individuals to embrace death: “The Order is about making death a part of your life. That means committing to staring down your death fears — whether it be your own death, the death of those you love, the pain of dying, the afterlife (or lack thereof), grief, corpses, bodily decomposition, or all of the above. Accepting that death itself is natural, but the death anxiety and terror of modern culture are not.”

The practices having to do with "digital media" and death that some find unsettling — including placing QR codes on headstones, using social media websites as mourning platforms, snapping photos of dead relatives on smartphones, funeral selfies, and illness blogging or deathbed tweeting— may be seen as attempts to do just that, materializing death and mourning much like Victorian postmortem photography or mourning hair jewelry. Much has been made of the loss of indexicality with digital images, which replace this physical process of emanation with flattened information, but this development doesn’t obviate the relationship between photography and death. For those experiencing loss, the ability to materialize their mourning — even in digital forms — is comforting rather than macabre.