Nature is conservative and not progressive. She reverts to type as soon as the reason for departure from it disappears. —Ernest E. Maddox, "Heterophoria" (1921)

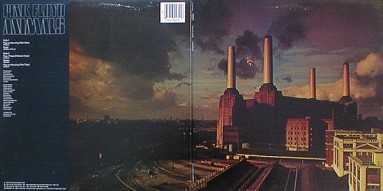

During production of Animals, Pink Floyd's 10th studio album, vocalist, bassist and songwriter Roger Waters hit upon the idea of tethering a 40-foot helium-filled pig to London's iconic Battersea Power Station and photographing it for the jacket. Hipgnosis, the design team behind many iconic rock album covers in the 1970s, realized Waters's vision, producing the giant inflatable pig for a planned three-day photo shoot. On the second day, however, December 2, 1976, fierce winds buffeted the airborne effigy until it broke free of its moorings.

The band had a plan for precisely this contingency. They kept a sharpshooter on hand to put a bullet in the pig should it somehow escape. Yet on the second day, the sharpshooter didn’t show; he believed the band had hired him for only one day. Thus the photography crew could only watch helplessly as the pig, nicknamed "Algie," floated off in the direction the English Channel.

Algie at large forced the closure of Heathrow airport, as officials feared the pig would drift into approach paths. A police helicopter chased it shortly after it broke loose, but the pig's rapid rate of ascent, estimated at some 2,000 feet per minute, sent it out of reach.

The tales of Algie-induced panic that ensued eventually reached the band. Pink Floyd's drummer Nick Mason recalls in his memoir, Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (2005), an "apocryphal" story in which a pilot spotted the pig as he came to land at Heathrow but refused to officially report it out of concern that flight control would think he had been drinking.

But imagine that flight, if it occurred. A tone cues the crew to make a last pass through the cabin to pick up trash and check for fastened seat belts. You return your seat to the upright position. Out the window, through the occasional break in an otherwise uninterrupted blanket of gray clouds you catch a glimpse of suburban London — tiny, cramped yet orderly. Then suddenly you are jolted by a forward heave, and in that moment of adrenaline you see what caused it: the enormous pink pig floating serenely, frayed guy wires undulating below its feet.

A culture-industry extravagance adrift, looming in congested airspace, no longer properly tethered, inadvertently disrupting the circuits of capitalism rather than fueling them, its symbology no longer safely contained by the product it was meant to promote, throwing complacent passengers suddenly into a panicked reckoning of their passivity. Arguably, this is a more powerful allegory than the one Waters had planned with the pig (let alone the one sketched by the actual songs on Animals).

The cover Hipgnosis ultimately produced is a bleak, soot-stained panorama, with the power station dwarfing not only the easy-to-miss pig balloon but also the surrounding city, cowering under massing clouds.

The power station is emblematic of an industrial capital in terminal decline. Each brick attests to the procedures of that economic order: the mobilization of huge amounts of money (the initial capital outlay for Battersea topped £2 million, inflation unadjusted), the equally huge capacity of the eventually completed project (about 243 megawatts), the monopolistic-technocratic impulse behind its conception (once finished, Battersea supplanted the power system that preceded it, a patchwork of much smaller municipal generation sites), and the stakeholders' mirage-like horizon of anticipation for returns on their investment (the long-term, capital-intensive infrastructure project would produce dividends only after several years).

In contrast to this stands Algie. To Battersea power station's ghost of capitalism-past, the pig is counterpoised as the ghost of capitalism-future — as insubstantial as the station is massive, as ephemeral as the station is enduring, as mercurial as the station is sober and imposing, as individualistic and distinctive as the station is collective and unprepossessing.

Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (2008), by Mark Blake, offers the standard account of the intended meaning behind the power-station/airborne-porker juxtaposition. Waters described the station as "doomy, inhuman" and proposed flying a pig between its four towers as "a symbol of hope."

Presumably the hopefulness had something to do with all the unlikely things that would proverbially come to pass once pigs fly. But at first listen, a less hopeful album than Animals is hard to imagine. In his contribution to Pink Floyd and Philosophy: Careful with That Axiom, Eugene (2007), Patrick Croskery sees the album as a "sonic portrait of a world without empathy" that teaches us that "hope is futile." Instead of hope there is universal "boredom and pain," as the plaintive opening track, "Pigs on the Wing (Part One)," would have it.

The follow-up to the deeply embittered Wish You Were Here, an album-length lament over how drugs, celebrity, and the music business conspired to make Pink Floyd's original leader, Syd Barrett, into a nonmusical, nonfunctioning mentally ill recluse, Animals would broaden its contempt to include virtually all of English society, divided Orwell-style into types of animal: dogs, pigs, and sheep, each with a long song dedicated to anatomizing their characteristic compromises and delusions. (As Tom Scharpling put it, "if Wish You Were Here is 'being in Pink Floyd sucks,' Animals is 'humans suck.'") The allegory is at best ambiguous, but generally the species are read as representing the various levels of capitalist society on the cusp of Thatcher's neoliberalist reforms: the pigs are the aloof elites; the dogs the servile, manipulative managerial class; and the sheep are the working masses from which the dogs extract value.

This sort of allegory leaves little room for social transformation or class mobility; dogs don't transmogrify into sheep. You are born with a destiny, the songs suggest, which they pitilessly lay out in a stream of elliptical taunts. And indeed, as Croskery noted, there is little room for empathy across species lines. Though the parameters of the good life of a pig or a dog or a sheep is prescribed, fulfilling those expectations proves impossible to manage. Instead Animals promises a drawn-out process of unravelling broken dreams and fantasies of revenge. But by giving vent to these hopeless feelings, it helps us accommodate them. By learning that we've been right all along to be depressed, we earn a rough sort of hope.

***

Most of the A side of Animals is taken up by "Dogs," a sprawling 17-minute track that contains no choruses, only verses. Unlike other side-long Pink Floyd epics like "Echoes," "Dogs" offers little in the way of trippy psychedelia; instead of spacey expansiveness, it delivers hectic strumming and anxious whining. The guitar solos are less evocative than monolithic, giant sonic slabs that hover ominously and reverberate. The deep studio echo, the down-tempo, laconic instrumental and vocal performances, the anal-retentive production, the various gimmicks and cold glosses of a vocoder or Moog synthesizer: These are the hallmarks of the late Pink Floyd sound, which the band evolved as a kind of womb to protect themselves from the consequences of their success — which, not incidentally, is the lyrical concern of "Dogs."

In "Dogs," David Gilmour, who sings the first half of the song, assumes the role of career coach, launching into a litany of prescriptions, each tailored to the exigencies of capitalism's latest iteration. With the first line — "You gotta be crazy, you gotta have a real need" — he signals the call to what affect theorist Lauren Berlant calls "cruel optimism," a vexed relation to seeking the good life on its conflicted, socially dictated terms. But what is worthy of being regarded as a "real need" is far from clear, and it dissolves into a series of defensive strategies. "You gotta sleep on your toes," he tells listeners, "and when you're on the street, / You gotta be able to pick out the easy meat." And that's not all. Listeners have other predatory obligations. "You gotta strike when the moment is right without thinking," Gilmour sings.These are dogs in a dog-eat-dog world.

The predation goes right on to the top as one climbs the ladder. "And after a while, you can work on points for style," Gilmour assures listeners, "Like the club tie, and the firm handshake, / A certain look in the eye and an easy smile." Graham Greene's Pinkie Brown

in Brighton Rock looks forward to the moment when he can move from back alleys to the board room, where the art of the deal depends crucially on sociopathic dissimulation. "You have to be trusted by the people that you lie to," Gilmour sings, "So that when they turn their backs on you, / You'll get the chance to put the knife in."No matter how high you ascend, there's no escaping the cutthroat competition: "You gotta keep one eye looking over your shoulder," until eventually you become "just another sad old man / All alone and dying of cancer." The wages of a dog's life of stress and striving are death. The best you can hope for is to become comfortably numb.

Irony-tinged pseudo-advice gives way in the next verse to Old Testament sermonizing, revealing the flip side of ambition for its own sake — a tautological pursuit that prompts an infinite regress of self-accusation. "And when you lose control," he sings, "you'll reap the harvest you have sown."

For the dog who has "succeeded," there's not an amassed bounty of happiness and property waiting for him; instead there is only weight, the physical analogue to a life's worth of bullying: "It's too late to lose the weight you used to throw around." Berlant notes that cruel optimism can involve "processes by which people hoard themselves in fear of dissolution." This works against the simultaneous yearning to have "the weight of being in the world" become "distributed into space, time, noise, and other beings." As Gilmour's harangue in "Dogs" suggests, the zero-sum, sociopathic tactics by which we achieve personal sovereignty are at the same time an accumulating burden, an encumbrance that refutes that sense of control it is supposed to supply. Power brings only a different sort of isolation from powerlessness, Throwing our weight around, a once invaluable asset, turns to a deadly liability as it becomes less figurative, and the illusion of power reveals itself as mere inert mass. The domineering, scheming, blustering subject is actually just a heavy solitary object. "So have a good drown," Gilmour bids him, "as you go down, all alone / Dragged down by the stone."

The brute fact of our existence in such a world compels us to adopt a second nature that, with time, becomes as characteristic as our first. What Gilmour defines in his cynical advice and scornful prophesy is a habitus. In Outline of a Theory of Practice (1977), sociologist Pierre Bourdieu wrote that the habitus is

laid down in each agent by his earliest upbringing, which is a precondition not only for the co-ordination of practices but also for practices of co-ordination, since the corrections and adjustments the agents themselves consciously carry out presuppose their mastery of a common code.

To achieve an illusion of individuality and autonomy requires negotiating one's complicity with our acquired habitus. It means coping with a condition in which advice is simultaneously penance: What we know we should do is also what we must already atone for for having been. Our destiny is circumscribed by habitus, but the dogs' habitus entails precisely autonomy from such limitation. Sartre’s famous maxim, “Existence precedes essence,” the concept of habitus complicates. Neither does existence precede essence nor does essence follow existence; they manifest, rather, an irreducible and immediate twofold imposition of structural determinations. This is the cage the dogs are in.

So the dogs, who chase the bone of individualism and whose pursuit of the good life has meant wielding power through craven boot-licking and betrayal with the hope that eventually this would resolve into the solid, invulnerable respectability of the pigs, are trapped by a habitus that precludes the rewards it sets them chasing.

The third movement of "Dogs" brings the reckoning: a brisk, Spanish-inflected acoustic rhythm guitar accompanies Waters, who takes over on vocals — the shift suggesting that he inhabits the persona of the backstabbing careerist Gilmour has condemned to drown. If Gilmour describes what you must do to get ahead, Waters reveals what this process does to you. Waters sings, "Gotta admit that I'm a little bit confused." Uneasy under censure, the victimizer presents himself as the victim of that age-old antagonist, circumstance. "Sometimes it seems to me as if I'm just being used," Waters remarks — though by whom is unstated. The truth he can't face is that he has used himself, instrumentalized his own being. As many sociopaths are made as are born.

The predatory virtue of opportunistic vigilance urged by Gilmour is now recast as a desperate survival strategy to cope with the dog-eat-dog Geworfenheit. "Gotta stay awake, gotta try and shake off this creeping malaise," Waters sings. His lyrical persona finds himself compelled to face with sober senses the Hobbesian war of all against all his morality has posited: "And the thing to do would be to isolate the winner / And everything's done under the sun, / And you believe at heart, everyone's a killer." After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Hence life in this gladiatorial pit demands self-deception and willful ignorance, which makes the ambiguity of who Waters is addressing — himself, Gilmour, his victims, listeners, God? — resonant. This ambiguity climaxes in a paradoxical litany of rhetorical questions without an answer, singling out a "who" that can't be known.

Who was born in a house full of pain.

Who was trained not to spit in the fan.

Who was told what to do by the man.

Who was broken by trained personnel.

Who was fitted with collar and chain.

Who was given a pat on the back.

Who was breaking away from the pack.

Who was only a stranger at home.

Who was ground down in the end.

Who was found dead on the phone.

Who was dragged down by the stone.

A dog’s life, indeed. Conditioned to follow orders, bear a leash and collar mildly, refrain from bad behavior, submit to the guidance of experts, and respond to their praise, the singer both mistakes and rejects the possibility that he has mistaken his servitude for freedom, his domestication for a Jack London–esque spirit of indomitability. Exemplifying Goethe's observation that "none are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free," he bids for “alpha” dog status, but breaking away from the pack brings only misery, isolation, defeat, illness, and demise. There is only the stone, the implacable Real, that drags Waters’s subject into a void opened by his own callous striving.

Bourdieu would likely concur with the Weltanschauung of “Dogs.” His hermetic system finds an apt image in the maze that Waters’s lyrical persona wishes to escape, if only by standing his ground. Even the impasse of stasis betrays a certain dynamism; standing your ground equally betrays a thorough implication in a structure. As John Milton famously put it, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” A dog-eat-dog world will inevitably and continuously summon forth more dogs eating and to eat. How could it do otherwise? It may be that our best bet for locking up the hounds is to release them.

***

With "Pigs (Three Different Ones)," the opener of side two of Animals, the predatory, sociopathic opportunists of "Dogs" cede the spotlight to three examples of grasping, entitled hypocrites — "charades" they are. These pigs are not cops or enforcers; rather they are akin to the haute-bourgeois politico pigs of Charles Manson's deranged imagination, by way of George Harrison's "Piggies." Their gluttony expresses itself as an apparent freedom from reciprocal social relations. Whereas the dogs were bound to self-contradiction by their habitus, doomed to pursue power through groveling, the pigs never need stoop. They sail above the power station, after all.

The first pig is a "well-heeled big wheel" who's too self-satisfied to conceal his transparent phoniness: "And when your hand is on your heart / You're nearly a good laugh." The second, allegedly modeled after Margaret Thatcher, is a "bus-stop rat bag," a "fucked-up old hag" who "radiate[s] cold shafts of broken glass" and is "hot stuff with a hat pin." She's conjures a similar sense of the sharp, jagged nature of abortive femininity of Dickens's Mrs. Joe Gargery

in Great Expectations, whose "square, impregnable bit" of "coarse apron [is] stuck full of pins and needles." The singer's response to this second pig is the same: "You're nearly a good laugh," Waters sings, "almost worth a quick grin." The last pig — "Hey you, White House" — is an uncloaked attack on Mary Whitehouse, a noted U.K. prude, bigot, and conservative crusader who sought to censor the BBC's television programming and strove, as Waters puts it, "to keep our feelings off the street." Again, Waters's lyrical persona can almost — but only almost — delight in her absurdity: "You're nearly a real treat."In these stifled, failed attempts to laugh the pigs away, we see the ramifications of cruel optimism at work again or, to use another of Berlant's phrases, "compromised endurance." The pigs can't quite be dismissed because they are structurally necessary alibis, bloated Big Others, cartoon depictions of evil that give meaning to life's stubborn, ordinary struggles. They allow us to overlook the ways in which we are attached to dog-like pursuits that damn us to perpetual frustration and stress, letting us cling to those attachments in the face of their futility. By authorizing us to nurse a keenly felt sense of persecution, they help us keep our feelings internalized and organized, "off the street," where they would necessarily become politicized, unstuck.

Yet the pigs are just ludicrous enough for us to almost laugh at their mastery over us in order to mitigate it. In Cruel Optimism (2011) Berlant points to "the knotty tethering to objects, scenes, and modes of life that generate so much overwhelming yet sustaining negation"; the fantasy of the pigs' heedlessness fits that function. The song's grinding, lethargic tempo — weirdly married to pseudo-funk syncopated bass runs — echoes formally this sense of relishing an impasse, of refusing to resolve the contradictions in "you're nearly a laugh but you're really a cry."

Animals as a whole tends to work this way on listeners, conjuring a totalizing and remorseless vision of an oppressive society that excuses, even glorifies the shifts we make in muddling through. As anyone who has listened to the album straight through can attest, it "generates overwhelming yet sustaining negation." It guarantees a vision of the world as an awful mess and endorses the sufficiency of our strategies of self-protection, the refuge we take in an entertainment product (like the album itself) that seems to "get it." It peddles a fantasy of an irredeemably broken world that demands our ironic distancing from it, a world in which the best we can do is consume apathy as entertainment so that no one will mistake us for ignorant rather than merely hopeless victims. Though our sense of sovereignty may be frustrated, stifled at every turn, Animals let us know we still are aware enough to realize it, and that gives impossible, paradoxical hope. The purpose of Animals is not to criticize the dogs and pigs. It is to teach us how not to become sheep.

***

With "Sheep" Pink Floyd picks up the tempo, as if intending to establish the band's impatience with the song's docile subject. Yet they also suggest docility with smooth jazz-organ noodlings played over ovine bleating. Menace arrives decisively, however, with the fade-in of a bass line recalling an earlier Pink Floyd song, Meddle’s "One of These Days," which memorably climaxes with a heavily treated voice croaking, "One of these days I am going to cut you into little pieces."

The song grows more ominous still with the entrance of lead guitar, whose bursts of syncopated, distorted notes come as so many lightning strikes over the sheep's pasture. Waters, once again assuming lead-vocal duties, barks out the opening lines: "Harmlessly passing your time in the grassland way." The key word is harmlessly; the open question this line introduces is how to pass time without lapsing into harmlessness, and without mistaking self-harm as a viable alternative, as a threat to the social order.

Waters's lyrical persona observes that a contemptible imbecility attends the sheep's docility: "Only dimly aware of a certain unease in the air," they fail to register what the ambient unease portends, perhaps merely chewing their cud with a degree of agitation. As if to prod them to a greater sense of urgency, Waters's lyrical persona warns, "You better watch out / There may be dogs about."

You can hardly fault the sheep for their obliviousness; the danger they face from the dogs lacks immediacy, figuring rather as mere atmosphere of peril, one which they can easily place out of sight and mind. Indeed, to perceive it requires the peculiar vision of an Old Testament prophet, which returns in the next two lines. "I've looked over Jordan and I have seen / Things are not what they seem." What rough beast slouches toward Bethlehem only Waters's lyrical persona has the privilege of knowing.

Waters is in no way willing to forgive the sheep's obliviousness, however. Taking their lack of awareness for complacency, he chides them. "What do you get for pretending the danger's not real?" he asks. But ovine is as ovine does. "Meek and obedient [they] follow the leader / down well-trodden corridors into the valley of steel." Only when they discover that which awaits them at the end of this corridor do the sheep become alarmed. "What a surprise!" sings Waters in a tone of mock sympathy, noting the "look of terminal shock in [their] eyes" that registers their acknowledgement that "now things are really what they seem," and that "no, this is no bad dream." It is, rather, the stark reality of the relationship between sheep and shepherd, whose husbandry is motivated not by benevolence of course but by ruthless rational economic calculation.

The irresistible forward thrust of "Sheep" abates for a moment, the slow-down signaled by a few sustained synthesizer notes. A vocoder-ed voice begins to recite a travestied version Psalm 23:

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want

He makes me down to lie

Through pastures green he leadeth me the silent waters by

With bright knives he releaseth my soul

He maketh me to hang on hooks in high places

He converteth me to lamb cutlets

For lo, he hath great power and great hunger

When cometh the day we lowly ones

Through quiet reflection and great dedication

Master the art of karate

Lo, we shall rise up

And then we'll make the bugger's eyes water.

Rather than the Lord making the speaker "to lie down in green pastures," as the original psalm reads, he makes the speaker "down to lie," ready to utter falsehoods. The tortured syntax continues in the next two lines — "Through pastures green he leadeth me the silent waters by" — before ceding to the sonnet-like volta of the third line: "With bright knives he releaseth my soul." Awesome more for his appetite than his justice, the Lord reveals himself as simply another dog, albeit one whose rapacity lies concealed behind calculated concern for his unsuspecting flock. Virtue and sin command the same wages — death — and thus their distinctions dissolve. Rather than lead his obedient charges out of the valley of death, the Lord leads them into it.

"Sheep," in other words, returns listeners to the world of "Dogs," where something akin to Georges Bataille's imminent law of eater and eaten governs affairs. Ingrained as it were in the essence of that world, slaughter and butchery lose any salience in moral terms and figure instead as both the efficient and final cause of all who inhabit this world. “There is no transcendence between the eater and the eaten,” Bataille writes in Theory of Religion (1989). “There is a difference, of course, but this animal that eats the other cannot confront it in an affirmation of that difference.” So it is with the Lord of "Sheep," a devourer of souls.

The speaker confronts the fact that his Lord, the ultimate Big Other, "maketh him to hang on hooks in high places" and "converteth him to lamb cutlets" precisely because it befits his Lord to do so, "for lo, He hath great power and great hunger."

Though this may prove difficult to accept, it represents the only way for the sheep to effect change. Messianic deliverance in the world of "Sheep" comes not from above or without but from within, "when cometh the day lowly ones / Through quiet reflection and great dedication / Master the art of karate." This art attained, the speaker and his kind "shall rise up / And then [they'll] make the bugger's eyes water."

"Sheep" preaches a sort of liberation zoology, complete with an eschatological vision of a peaceable kingdom arriving only after great struggle. Indeed, the song enacts this animal Armageddon before the listener's ears. During the spoofed psalm the bleating of sheep grows louder and more insistent, their uproar granting them a sense of their numbers and the power latent in them. The song ends with a brief account of the sheeps' revolt and subsequent victory. "Bleating and babbling we fell on his neck with a scream," Waters sings. The Shepherd Lord and his canine cohort defeated, "Wave upon wave of demented avengers / March cheerfully out of obscurity into the dream."

But for what have they surrendered the earlier dream of the grassland where they had passed their time away? "Have you heard the news?," cries Waters. "The dogs are dead!" Of course, no promise of universal freedom from future exploitation informs this overthrow. New oppressors, harder to distinguish than the old ones since they come from the sheep's ranks, rise to command the hierarchical structure, which remains unchanged. "You better stay home," Waters warns. "And do as you're told / Get out of the road if you want to grow old." New boss: same as the old boss.

***

As "Sheep" fades into silence, a lone acoustic guitar fades in, sounding familiar chords. "Pigs on the Wing (Part Two)" supplants the dismal hypothetical of the first part — "If you didn't care / What happened to me / And I didn't care for you" — with an acknowledgment: "You know that I care what happens to you / And I know that you care for me too." Apparently gone at this point is the necessity for finding feeble ways of coping with a heartless, pitiless world. The singer takes solace in the knowledge that his addressee shares his burden: "So I don't feel alone the weight of the stone." Love, the most cruelly optimistic attachment of all, makes us depend on the burden that we share; the stone confirms the real possibility of the bonds we yearn for.

Yet more a sense of resignation than triumph attends Waters's words. Peace comes only with retreat, with withdrawal into a personal relationship and the cozy little abode Waters and his addressee can build to protect it. "Now that I've found somewhere safe to bury my bone," he continues. "And any fool knows a dog needs a home / A shelter from pigs on the wing." The song thus ends on the image of porcine flight with which Animals began, leaving you to wonder how seriously to take the social and political insights offered in it and the rest of the album's tracks. Is the listener to understand that plunder and theft are inevitable, that the best he can hope for in life is a place to secret away whatever spoils he may manage to win for himself?

All things considered, Animals seems an improbable album with which to buoy a band's stadium-rock status. Much like the punk music that the members of Pink Floyd considered from the serene distance afforded to rich musicians who were spared the ravages of recession, the songs on Animals struck a defiant pose against the very industry that succored it. As Nicholas Schaffner writes in Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey (1991), the album "was ... uncompromising — courageous even — in its format." It seemed determined to put then-infant AOR radio through a stress test. "Pink Floyd had, of course, always been renowned for their long and winding compositions," Schaffner continues. "Animals consisted pretty much of nothing but. This left few openings even for 'progressive' FM radio programmers: no readily excerptible choice five-minute 'bites' like 'One of These Days,' 'Welcome to the Machine,' or the individual tracks from Dark Side of the Moon." Animals instead seemed bound for deep space, commercially speaking; absent any singles, "there was little chance that [Dark Side’s] sales phenomenon could remotely be matched this time around."

To the rescue rode Pink Floyd's label, EMI. It hedged the long odds for success faced by Animals with a comprehensive media rollout, which began six weeks prior to the album's release date with the broadcast of The Pink Floyd Story. An oral history in the band members' own words, The Pink Floyd Story aired late-1976 through early 1977, its final installment coninciding with the street date for Animals (January 23, 1977). Further exposure came in the form of the broadcast of the album's first side by the legendary disc jockey John Peel.

The sustained pushed paid off; Animals debuted near the top of the charts, No. 2 in the United Kingdom and No. 3 in the United States. Perhaps you could chalk it off to a momentary lapse in reason, but Pink Floyd's decidedly uncommercial new album appeared to defy its own nihilism.

That Animals proved a hit seems all the more improbable when you consider that, in addition to its radio-unfriendly format and sequencing, it "hardly sat well alongside punk calling cards, The Clash's first album and The Sex Pistols'

Never Mind the Bollocks," as band biographer Blake observed. "But nor did it fit with the music being made by Pink Floyd's beardy contemporaries." This owed almost entirely to a difference in preoccupations and commitments. "These bands were not wringing their hands over corporate greed, man's inhumanity to man, or railing at the 'fucked-up old hags' that tried to censor what we watched on TV."Though the band had for some years prior to the release of this album counted themselves among "the high-fidelity / First-class traveling set," of which they sang in their earlier hit, "Money," their lyrical gravamens remained staunchly those of the put-upon struggling classes from whose ranks would emerge the stars of the punk and postpunk firmament.

Yet for all its denunciations of dogs' remorseless predation, pigs' greedy hypocrisy, and sheeps' dishonest meekness, Animals leaves listeners with a deeply conservative message. By the time the final song has ended, you're given to understand that the war of each against each, rather than disappearing with the ascendancy of first the centralized state and later parliamentary democracy, will always be pursued by other means. Freedom stands as the chief illusion to which you can fall victim. Everyone must cast his lot with either pigs, dogs or sheep. Only security is a good worth pursuing, by any psychic means necessary. Run with the dogs, win a mate, snatch a few bones while keeping one eye on the sky for any armada of oinkers, make haste to your den and you'll have accomplished all that you can reasonably hope to.

Immersion in the Animals worldview served to soften up listeners, particularly those living in the U.K., for the tough reforms that loomed on the horizon. "By the summer of 1977, unemployment was up to 1.6 million, 6 percent of the workforce," writes John Savage in England's Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond (1991). To make matters worse, "the public service cuts demanded by the IMF began to bite, and the polarizations of the time found their expression in street violence."

The sheep had begun to feel their oats, and the pigs and dogs mobilized to sweep Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government to power two years later. Indeed, many of the policies and sentiments of that regime chimed with themes addressed on Animals. With its privatization of council housing, it promised every dog a home and a place to bury his bone, while Thatcher's maxim “There is no such thing as society" summarizes the pessimistic view elaborated on the album of collective human existence, which owes nothing to Marx's cherished notion of "species-being" and everything to the mere accidents of speciation. As neoliberalist protocols took hold, there was only what Berlant calls "fantasmic intersubjectivity" for sale.

Millionaires in the ticklish position of bemoaning the vice and excesses of power and wealth, Pink Floyd found themselves caught between relevance and hypocrisy. "By the mid-1970s, there was a growing unease among some critics and fans with what they saw as the complacent attitude of rock's super-league bands," Blake writes. "Pink Floyd's financial success, general aloofness and age ... made them a target for critics who believed that rock music should be made by younger, hungrier bands." The thirtyish members of Pink Floyd no longer cut such romantic figures. David Gilmour had taken himself to siring children, Roger Waters had taken up golf, and drummer Nick Mason had taken to collecting vintage automobiles. Were you to ask the lean, amphetamine-amped strivers, who worried about getting nicked by bobbies for hopping tubeway turnstiles and other minor acts of defiance, what they made of the plush lives enjoyed by the members of Pink Floyd, they'd call it riding the gravy train.