Guantánamo Diary's missing passages connect it with the US empire's deeper history of far-flung capture and detention networks

?? ????? ??????? ??????

????? ???????? ??????

-???? ??????

From the window of my little cell I can glimpse your even bigger cell

—Samih al-Qasim

Ould Slahi, a 44-year-old Mauritanian, has now spent nearly a third of his life behind bars without charge. He composed the text in 2005 in the English he learned from his captors, who in turn sought to yank back the “gift” of language by redacting 2,500 words and passages before releasing the manuscript. The published version faithfully reproduces the censor’s black marks.

The longest redacted passages in Ould Slahi’s book are his stories of polygraph examinations and a poem he wrote – both technologies of the soul.

The simultaneous publication of Guantánamo Diary in nearly a dozen languages is part of a celebrity-studded campaign by the American Civil Liberties Union encouraging U.S. president Barack Obama to close the prison before he leaves office

The book has been widely praised by reviewers for confirming a well-established liberal narrative that criticizes the War on Terror mainly as a narrow problem of torture in an abstract debate about the rule of law: the U.S. betrayed its lofty goals and lost its way after 9/11. And Guantánamo Diary is indeed replete with vivid descriptions of torture and its gradual, inexorable tearing through of body and spirit (though Ould Slahi’s first-person narration consciously preserves a sense of dignity, even for his captors). Here, the liberal critique is girded with the narrative voice of a witty, fair-minded immigrant who is careful not to exaggerate his woes and even highlights the good guards he meets, subtly reassuring us that “we” are still fundamentally a good, decent country.

Ould Slahi’s memoir, however, is far too interesting and important to be left solely to the War on Terror’s liberal—and predominantly white—critics. Let us recognize Guantánamo Diary as something more: an extraordinary artifact of U.S. empire at the dawn of the 21st century, an empire that operates mostly through indirect control abroad while building a racialized carceral state of unprecedented proportions at home. Ould Slahi’s shackled peregrinations along some of that empire’s darker passages allow him to see his experience not as a rupture with U.S. history, but as part and parcel of it. “You’re holding me because your country is strong enough to be unjust,” he tells his captors. “And it’s not the first time you have kidnapped Africans and enslaved

Like many of his fellow detainees at Guantánamo, Ould Slahi has always been a migrant. The son of a nomadic merchant, he won a prestigious scholarship in 1988 to study in what was then West Germany. From there, Ould Slahi made several trips during his winter breaks to Afghanistan, joining the jihad against the Soviet-backed government in the years before al-Qa‘ida declared war on the United States

In the eyes of the U.S. government, these acquaintances, kinship ties, and patterns of traveling while Muslim must have been dots crying out to be connected. In order to do so, it tried to turn Ould Slahi’s itinerant nature against him, by targeting him at his most vulnerable: while in transit. In January 2000, he was arrested while passing through Senegal on his way home. Several days later, the U.S. put him on a charter flight to Mauritania for several more weeks of interrogation. “It was the first time that I shortcut the civilian formalities while leaving one country to another,” Ould Slahi ironized. “It was a treat, but I didn’t enjoy it.”

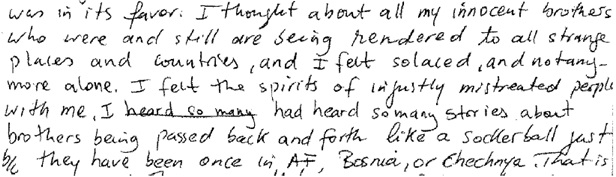

In both countries, Ould Slahi was questioned by the local authorities and U.S. agents, each capable of pointing to the actions of the other to excuse their own behavior. In a way, the book’s title is a misnomer, for a third of his account takes place in prisons other than Guantánamo. Ould Slahi’s experiences of detention in at least five countries are a reminder that the internment camp in Cuba is more than simply an offshore aberration from U.S. justice, but part of a global web of shadowy detention practices that predates 9/11. Ould Slahi knows he is not alone in this experience (this passage is taken from Ould Slahi’s manuscript rather than the published book, but the text is virtually identical):

I thought about all my innocent brothers who were and still are being rendered to all strange places and countries, and I felt solaced, and not any more alone. I felt the spirits of [u]njustly mistreated people with me, I heard so many had heard so many stories about brothers being passed back and forth like a soc[c]erball just b/c they have been once in [Afghanistan], Bosnia, or Chechnya

After his release, Ould Slahi found a job and lived at home until shortly after 9/11,

In an extraordinary passage, Ould Slahi recounts being personally handed over by Mauritania’s secret police chief at the time, Deddahi Ould Abdallahi

Ould Slahi spent the next eight months imprisoned at the headquarters of Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate in Wadi al-Sir, on the outskirts of Amman. Between long interrogations and occasional beatings he observed the misunderstandings, breakdowns, and tensions in the outsourcing of torture. His Jordanian jailers confronted him with intercepted emails and demanded that he decipher suspicious passages, mistaking their own misapprehension of multiple translations from German to English to Arabic for some kind of coded language. In Ould Slahi’s telling, the Jordanians came to realize that there was no reason to hold him but nevertheless needed to convince their American patrons of their earnest attempts to break him. When they finally recommended his release, Washington was only further angered and eventually decided to cut out the middleman and take Ould Slahi into its own hands.

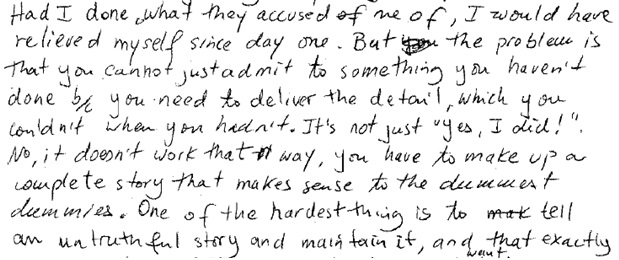

Had I done what they accused of me of, I would have relieved myself since day one. But

youthe problem is that you cannot just admit to something you haven’t done b/c you need to deliver the detail, which you couldn’t when you hadn’t. It’s not just “Yes, I did!”. No, it doesn’t work that way, you have to make up a complete story that makes sense to the dum[b]est dummies. One of the hardest thing[s] is tomaktell an untruthful story and maintain it …

The perversity of torture lies not simply in the possibility that tortured prisoners will confess to anything to make the pain stop; it is that the torturers will also demand that you perform your subjection with creativity and enthusiasm. That you will fill in the details they want corroborated and make up new ones to be tested on other prisoners; and that you will continue to fail and retake those tests.

After the interrogators “broke” Ould Slahi, his facility with the English language made him a favorite. They stopped taking notes in his interrogations and instead brought him a laptop so he could write up “intels” himself. “During this period I wrote more than a thousand pages about my friends with false information,” he recounts. “I had to wear the suit the U.S. Intel tailored for me, and that is exactly what I did.” The Guantánamo dossiers released by Wikileaks are indeed littered with allegations sourced to Ould Slahi, including in the files of friends he mentions in the memoir. Ould Slahi at one point asked to be resettled in the United States, citing fear of retaliation.

Eventually, Ould Slahi was moved to a special hut with better conditions, where he was neighbors with an Egyptian who was also “cooperating” with interrogators. He was given “gifts” like a pillow, allowed to watch movies, and gained access to the pen and paper with which he wrote this memoir. Guantánamo Diary is a document made possible by collaboration and also an act of defiance to it. Ould Slahi is calling out for justice, but he seems also to be doing penance, seeking to undo some of the harm he was forced to wreak on others.

Guantánamo Diary usefully highlights the connections between the offshore prison and the carceral state on the mainland. Conservatives and liberals alike tend to embrace the notion that the U.S. criminal justice system is exceptionally just and focus their disagreement on whether this system should include War on Terror detainees as well. There is a fine line here between seeking access to courts for strategic benefit versus trying in vain to flatter the national ego into showing some kind of clemency. Yet despite the unbearable torment of his situation, Ould Slahi harbors no illusions on this score. After spending eight months in Jordanian custody, Ould Slahi stills finds the possibility of prison in the United States a terrifying one: “I was thinking about life in an American prison… and the harshness with which they treat their prisoners.” When an interrogator at Guantánamo expresses concerns that detainees are exploiting “our liberal justice system,” Ould Slahi muses, “I really don’t know what liberal justice system he was talking about: the U.S. broke the world record for the number of people it has in prison.” Ould Slahi pointedly refrains from partaking in the perverse celebration of the U.S. criminal justice system that tends to frame mainstream War on Terror debates.

Perhaps the most vivid example of the links between Ould Slahi’s offshore plight in Guantánamo and the racial-carceral state on the mainland is embodied in one of his chief torturers. As detailed by The Guardian, Richard Zuley was a Navy reservist sent to Guantánamo, where he applied techniques practiced for decades on poor Black people as a police detective in Chicago. Guantánamo gave Zuley an opportunity to adapt his hometown racist policing experience to the outsourcing and rendition practices of empire. He achieved this by using Egyptian and Jordanian translators to enact a kind of racialized good cop-bad cop scenario meant to terrify Ould Slahi into seeking the tender mercies of white American justice. Under Zuley’s direction, Ould Slahi was blindfolded and taken to a speedboat, where the Arab translators made sure he could hear them promising good results to their American overseer. They spent the next several hours cruising around the bay, viciously beating him. Shortly thereafter, Zuley and his Egyptian adjunct make a show of debating in front of Ould Slahi which one will get to interrogate him:

“I wish ????????? ????????? let me in to have a little conversation with you,” said the Egyptian in Arabic, addressing me.

“Stand back now; let me see him alone,” [Zuley] said [in English]. I was shaking, listening to the bargaining between the Americans and the Egyptians about who was going to get me. I looked like somebody who was going through an autopsy while still alive and helpless.

Siems excised Zuley’s next line from the book:

“You’re lucky today b/c I’m in a good mood. I am sorry that I have to compromise the values upon which my country was built, and which made my country the greatest in the world.

The book then picks up with the rest of his speech:

“You are going to cooperate, whether you choose to or not. You can choose between the civilized way, which I personally prefer, or the other way …”

The editorial cut here is telling: Whatever Siems’ reasons, the deleted text disturbs the idea that the brutality of Guantánamo is “outside” America and what it stands for. As performed by Zuley, the narrative of the U.S. betraying its values isn’t—as liberals imagine—a lament. It’s a threat, one understood all too well.

For years after 9/11, lawyers and human rights activists sought to extend the jurisdictional reach of U.S. federal courts to Guantánamo detainees in order to win their freedom. In 2008, the Supreme Court finally allowed habeas corpus petitions to proceed and Ould Slahi was one of many detainees to win their cases. But his victory was short-lived: an appeals court blocked his release and ordered the lower court to redo the case using a much broader and more flexible legal standard for detention. That was more than four years ago; the case remains in limbo, with Ould Slahi’s lawyers understandably wary of risking a judicial decision confirming the legality of his detention and wisely opting for political pressure instead.

The alternative to extending the reach of courts has been to bring the prisoners onshore instead, where they could seek access to a broader set of constitutional and other rights. For years, the Obama administration has considered proposals to relocate detainees to prisons on the U.S. mainland. This would be celebrated by many liberals as a step toward the rule of law.

But importing Guantánamo—rather than closing it—would likely be a disaster. Of the 122 remaining detainees, there are a few dozen whom the government deems too dangerous to release but against whom there is insufficient evidence even for U.S. courts. Ould Slahi is likely in this category. The inevitable right-wing backlash to bringing alleged “terrorists” into the United States would leave judges with little choice but to decree that the detainees’ relocation to the mainland does not guarantee them any additional rights. Such rulings in turn would provide precedents that could bleed over into litigation around other prisons, in both the criminal justice and immigration systems. Instead of drawing attention away from the carceral state as it does now, Guantánamo could help make it even more entrenched and punitive.

In the meantime, the politics of visibility, of fixating on the spectacle of Guantánamo, continue to struggle against an empire built on more invisible forms of outsourced detention abroad and mass incarceration at home that hide in plain sight. This misrecognition runs deep. In June 2013, shortly after the appearance of long excerpts from Ould Slahi’s memoir in Slate renewed public interest in his case, a U.S. military plane landed in Nouakchott. News reports trumpeted the return of Ould Slahi and the other Mauritanian held at Guantánamo, Ahmed Ould Abdel Aziz. The narrative temptation was obvious: injustice, exposed to the sunlight of public scrutiny, was forced to give way. Unfortunately, it quickly emerged that the flight wasn’t coming from Guantánamo nor was it there to set anyone free. Instead, it was ferrying home a Mauritanian secretly held in Bagram for more interrogation.